Deportations: rights and responsibilities

What could possibly go wrong?

There are countless documented instances of human rights violations occurring in relation to or during deportations, and violations have also taken place during Frontex-coordinated expulsion operations. They include the use of racial profiling for the purpose of attempting to fill charter flights; the physical abuse of deportees by escorts; the failure of national authorities to keep records up-to-date regarding appeals by people due to be deported or to offer individuals the opportunity to apply for asylum; and the enforcement of removal orders handed down by inadequate or flawed decision-making procedures.

In Spain and Italy, raids and identity checks based on ethnic profiling have been used to try to fill deportation flights booked to travel to specific countries. For example, in January 2017 the Italian interior ministry issued a memo to police forces concerning the scheduling of a deportation flight and interviews with Nigerian authorities. The memo explicitly instructed police services to target Nigerians, indicating that 95 places had been reserved in detention centres,[1] and proposed “targeted services for the purpose of tracking down Nigerian citizens in an irregular situation in the national territory."[2]

Filippo Miraglia, vice president of the association ARCI, highlighted the illegality and discriminatory nature of this initiative, which he called "a collective expulsion, forbidden by law, enacted on the basis of nationality, and hence discriminatory, regardless of the individual people's situations". He explained that people do not have "irregular Nigerian" written on their forehead, and there were thus strong concerns over how police forces would implement the instructions in practice. Giorgio Bisagna, a lawyer for the Adduma association, expressed concern over the intention to enact a "collective expulsion of irregulars" and warned that that "you cannot carry out a sort of round-up.”[3]

This is not the only time the issue of collective expulsions, which are prohibited by European human rights law,[4] has been raised in recent years. In October 2016, eight Syrians were returned to Turkey in a Frontex-coordinated flight from the Greek island, Kos, after the entry into force of the EU-Turkey deal.[5] The passengers were reportedly never given the opportunity to apply for asylum and were not informed of the destination of their trip (they believed they were flying to Athens). Amnesty International denounced the incident as refoulement.[6] In 2012, Migreurop accused Frontex of legitimising the German government’s policy of “systemic expulsion against the Roma community” through the organisation of return flights on which a significant number of passengers had had asylum claims refused in accelerated procedures, potentially infringing the prohibition against collective expulsions.[7]

Frontex’s involvement with expulsions from Greece also raises serious human rights questions. On the Greek islands, the “geographical restriction” that prevents people from leaving for the mainland has created appalling and widely reported over-crowding, insufficient services and limited or no access to healthcare. Fundamentally flawed decision-making procedures compound the problems created by utterly inadequate living conditions. Human Rights Watch has described the hotspots as “some of the most appalling mismanaged, and dangerous refugee camps in the world.”[8] Fast-track assessment procedures, the consideration of Turkey as a “safe third country” for Syrians without genuine individual assessments, lengthy delays in decision-making, and a lack of interpreters all call into question the validity of decisions made by the Greek authorities[9] (with the assistance of agencies such as the European Asylum Support Office, EASO, whose role has also been the subject of stern critique[10]). According to the Greek Council for Refugees, the lack of available legal assistance means that many people are returned unaware that they could have claimed asylum in Greece. The Turkish authorities, meanwhile, have claimed that Greece illegally deported almost 60,000 people.[11]

Frontex has been closely involved in implementing the flawed procedures and appalling living conditions to which people are subject prior to deportation from Greece, for which it has received strong criticism. The Greek Ombudsman has highlighted a failure to maintain medical files and carry out ‘fitness to travel’ checks on deportees; a lack of individualised assessment regarding the use of restraint; and the failure to take into account individuals making fresh claims for international protection with new evidence.[12] Frontex, by consenting to cooperate with removals from Greece – including by deploying return specialists to the country – is legitimating unfair and unjust procedures and executing decisions based on violations of fundamental rights.

Moreover, the serious discrepancies in the asylum determination systems of different EU member states mean that individuals of the same nationality have a vastly differing likelihood of receiving international protection in the EU, depending on the state in which they lodge an application.[13] The issue has been ongoing for years – in Greece, recognition rates sank as low as 0.04% at first instance hearings in 2010. This was one of the reasons that the ECtHR essentially banned ‘Dublin’ returns to the country – anyone returned there from another member state faced the risk of refoulement.[14] The result of such unfair asylum procedures may be that refugees are sent back, via a Frontex-coordinated operation, to places where they are at risk of being tortured or persecuted.[15] Frontex return specialists have been deployed in both Greece and Bulgaria – both countries where serious concerns have been raised over the quality of decision-making[16] – to assist with expulsions.

The Council of Europe’s Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT) has monitored four Frontex-coordinated expulsion operations in the last five years, with numerous critiques raised in each subsequent report.[17] Recently, EUobserver highlighted the physical abuse of a deportee on a flight bound from Germany for Afghanistan. In order to enforce ‘compliance’, an Afghan man had his testicles repeatedly squeezed and was subjected to restraint techniques which prevented him from breathing properly.[18] CPT officials reported the situation to the German authorities, who responded to their concerns, although they did not pass any information to Frontex, which coordinated the flight. The agency said it “may even have stopped the return operation to Afghanistan if it had known.”[19] However, as EUobserver reported, Frontex staff were on board the flight and did not report the abuse to the agency. This suggests that there are some serious problems with the procedures in place.[20]

The information that is available to the agency is crucial in relation to its coordination of forced return operations. In 2015 the Council of Europe’s anti-torture committee (the CPT) monitored a Frontex-coordinated deportation from Italy. They interviewed 13 Nigerian women in a detention centre who were due to be put on the flight, and found that they had all appealed against the initial rejection of their applications for asylum. Although this did not automatically suspend the removal order, the expulsion of seven of those women was subsequently halted before the flight departed. In the case of another woman, “the competent court had decided to grant suspension of removal,” but this was only communicated to the authorities “after the joint flight had departed from Rome airport.” The report highlighted that: “No information as to the pending legal procedures could be found in the women’s removal files. Apparently, such a state of affairs is not unusual.”[21] While this may be the fault of the national authorities, it remains the responsibility of Frontex to ensure that the deportation orders handed down against individuals are enforceable.

In May 2019, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) denounced the Hungarian authorities for giving two families from Afghanistan the choice of either “entering Serbia or being flown back to Afghanistan on a flight organized by Frontex”. The UNHCR advised Frontex “to refrain from supporting Hungary in the enforcement of return decisions which are not in line with international and EU law.”[22] However, while the agency must ensure that an enforceable return decision exists, it cannot enter into the merits of that decision. The Council of Europe and Frontex’s own Consultative Forum on Fundamental Rights have both recommended that the agency cease operations at the Hungarian-Serbian border given the “systematic violations of human rights in the transit zones”.[23] The fact that it has not done so calls into questions its stated commitment to its fundamental rights obligations.

Finally, there is the issue of what happens once an individual arrives in the country of ‘return’. According to the organisation Rights in Exile: “What happens to rejected asylum seekers post-deportation is still largely unknown. They might be apprehended by state security and sent to prison, tortured, tried for treason, or even killed.” Nevertheless, a significant amount of evidence has been gathered on the risks faced by deportees upon their return ‘home’.[24] In 2018, Zainadin Fazlie was shot and killed by the Taliban following his deportation from the UK to Afghanistan, after the introduction of the ‘deport first, appeal later’ rule.[25] Despite the evident risks, states do not monitor what happens to individuals after they are deported – yet where this leads to mistreatment or abuse, the deportation could be considered as refoulement.[26] While Frontex has no say in the decisions handed down by national authorities, it has a positive obligation to prevent refoulement. The 2019 Regulation introduced new references to engagement in “post-return” activities, and a ‘roadmap’ drawn up by Frontex and the Commission foresees the adoption of an ‘Action Plan on expanding Agency’s return support capacity for MS on post-arrival and post-return’ from autumn 2020. What exactly that will entail remains to be seen.

Legal accountability for fundamental rights violations

Decisions over who may remain on the territory of the EU ultimately rest with the administrative and judicial authorities of the member states. Frontex cannot assess the merits of the return decisions it enforces or review a returnee’s failed asylum claim. Moreover, the return escorts that may use abusive means of restraint have, until now, been staff of national authorities, rather than being directly employed by the agency. The 2019 Regulation allows agency staff to act as escort officers, which changes this equation.

While the agency may not be directly responsible for the (in)effectiveness of the national procedures and the misconduct of national officers, it still has a positive duty to ensure that the operations it conducts will not result in violations of fundamental rights. Frontex, like all member states, institutions, agencies, bodies and offices of the EU is bound by the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (CFR) and the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR), to the extent that the latter is represented in the development of general principles of EU law. In this regard, the agency has negative obligations to not actively violate human rights, as well as positive obligations, according to which it should protect human rights by preventing foreseeable violations.

The agency has a wide range of supervisory and monitoring powers, amongst which is the duty of the Executive Director to suspend or terminate an operation when serious and consistent violations are taking place and the presence of forced return monitors, which should report any human rights-related incidents to the agency. Frontex staff present on flights, for example to oversee the running of the operation, should also inform their superiors should they become aware of a violation or potential violation.

To the extent that the agency is informed that a violation is taking place, it is obliged to act within its powers to prevent that or similar violations in the future. If the agency does not utilise its supervisory role and fails to take such action, it may incur legal responsibility next to the primary responsibility of the member state. Such responsibility may also arise if there are legitimate reasons to believe that Frontex should have known of such violations, even if it claims that it had no knowledge thereof. This could for instance be the case of return flights from Hungary, given the systemic and well-reported violations at the Hungarian-Serbian borders, as mentioned above. Frontex’s legal responsibility may be clear in principle, but so far advice from the UNHCR to suspend support for return operations in Hungary due to their inconsistency with international and EU law seems to have gone unheeded by the agency, and legal responsibility has not been incurred in practice.[27]

Moreover, responsibility may arise from other Frontex activities, for example erroneous age registration, which may result in the unlawful deportation of a minor and the violation of the rights of the child. The new powers granted by the 2019 Regulation increase the possibility for Frontex to be held responsible for fundamental rights violations during its returns, especially since such return flights may be conducted in the agency’s own aircrafts, by the agency’s own escorts.

Finally, the agency’s new role in “the collection of information necessary for issuing return decisions,” even though the ultimate authority for issuing the decision rests with the member state, could lead to the agency exercising informal influence beyond its mandate. This could give rise to legal responsibility resulting from the de facto powers of the agency, something that would not be unprecedented. Such concerns have been expressed by NGOs and the European Ombudsman with respect to the extent of the involvement of the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) in assessing asylum applications in Greek hotspots, as in practice the national authorities rely disproportionately on the agency’s assessments.[28]

Since there is indeed scope for its legal responsibility, the agency should take certain measures in order to prevent violations, for instance with respect to the use of forced return monitors, while its accountability needs to be ensured, through fora and procedures in which Frontex has to answer for the impact of its activities upon fundamental rights. Next to mechanisms of administrative accountability, such as the individual complaints mechanism and the Frontex Fundamental Rights Officer, judicial accountability is of the utmost importance.

While the officers participating in a joint operation fall under the civil and criminal jurisdiction of the member state hosting the operation, the accountability of the agency itself is a much more complex matter. Due to the exclusive jurisdiction of the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) over matters regarding the legality of EU acts and the liability of EU institutions and agencies, national courts cannot assess the lawfulness of Frontex’s actions. However, the ability of individuals to access the CJEU is limited,[29] which significantly restricts the possibilities for Frontex to be held legally accountable. This issue, combined with the lack of transparency over the agency’s activities and the lack of clarity over its responsibility, is why a case regarding the human rights obligations of Frontex has yet to have its day in court, even though the possibility for such a case has existed since the Lisbon Treaty came into force. While there are still available legal avenues to pursue before the CJEU, the road to the legal accountability of Frontex will remain half-closed until the EU finally accedes to the European Convention on Human Rights,[30] allowing for individual access before the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) in Strasbourg.

The use of force: restraints and escorts

In 2014 the European Ombudsman carried out an inquiry into forced removals coordinated by Frontex. One of its recommendations was that the agency seek to document “the means of restraint allowed for return operations in each Member State,” and to publicly list “those restraint means to which it would never agree in a JRO.”[31] There is good reason for doing so. In 2010, the Institute of Race Relations published a list of the 14 people who had died during deportations from European countries since 1991, noting that the “official cause of death in most cases was positional asphyxia or cardiac arrest,” the former most likely caused by restraint techniques used against deportees.[32]

Frontex responded to the Ombudsman that it had “launched such a project itself” and was seeking the relevant information from the member states, after which it would analyse the responses “to ascertain if any means of restraint should not be permitted during JROs coordinated by Frontex”. The agency subsequently published a ‘Guide for Joint Return Operations by Air coordinated by Frontex’, which contains a list of restraints that are prohibited in those operations: “metal chains used to restrain hands or legs”; “straightjackets”; and “plastic ties not specifically designed for handcuffing or for leg restraint.”[33] The document stipulates that “compliance of Member States with this list is considered by Frontex to be a condition for participation in a JRO, based on the permissible restraints of the organising member state (OMS), coordinated by the Agency.” Furthermore, according to a Frontex training presentation, the Code of Conduct for JROs prohibits “measures that can provoke asphyxia or the use of sedatives,”[34] although only the latter is explicitly mentioned in the Code.[35]

It remains impossible to know the types of restraint that are permitted in the agency’s return operations, apart from via formal requests for access to documents (and this is still only retrospective). The table below summarises the information concerning restraints contained in implementation plans and operational overviews covering nine JROs conducted in between 2016 and 2018, which were released to Statewatch in response to an access to documents request.

| JRO | Hand cuffs | Body cuffs | Head protections | ||||

| Steel | Velcro | Plastic | Textile | Helmet | Spit mask | ||

| 09/03/2016 to Nigeria | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 27/04/2017 to Serbia | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| 11/05/2016 to Pakistan | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N |

| 31/01/2017 to Serbia | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| 03/05/2017 to Nigeria | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 07/06/2017 to Pakistan | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| 18/01/2018 to Serbia and North Macedonia | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| 24/09/2018 to Pakistan | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 12/12/2018 to Nigeria and Gambia | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Table 5: Restraints used in selected Frontex joint return operations, 2016-18

Those responsible for applying restraint to the people being removed are referred to as escorts. Forced removals necessarily require the use of escorts to control the movements and activities of deportees, who may attempt to prevent or frustrate their own expulsion. Over the past 30 years a significant body of documentation (in the form of guidance, instructions, manuals, and so on) has been developed by state and non-state actors to govern the actions of escorts, in an attempt to ensure that as little physical harm as possible is done during the deportation process – a primary example of the “constant tension between norms and violence” that is always at play in forced removal proceedings.[36]

The number of escorts to be deployed on any given deportation operation, and the type of restraints that may be used, is determined by national authorities and is supposed to be worked out on the basis of individual risk assessments for each deportee. According to the EU guidelines on joint removal operations, national authorities should undertake “an analysis of the potential risks” and engage in mutual consultation to determine the number of escorts to be deployed.[37] Frontex recommends that each state involved in a joint operation “carry out an individual risk assessment of their returnees (based on factors such as previous behaviour and removal history),” to establish the number of escorts needed as well as the type of coercive measures that may be deployed.[38]

The UK Home Office’s instructions on “risk assessment and use of restraints on detainees under escort,” which deals with the transfer of detainees from detention centres to hospitals, police stations, airports or any other location, run to 15 pages and refer to a series of other relevant training courses and manuals with which escorts must be acquainted. The instructions set out factors to be taken into consideration regarding the use of force in general, and with regard to specific types of equipment (handcuffs, waist restraint belts, leg restraints and the “mobile chair”). The document notes that “where the use of restraint equipment is planned a minimum of two DCOs [detention custody officers] is mandatory to affect the move.”[39] Germany also reportedly follows the practice of generally assigning two escorts to each detainee, unless they present “a high security risk” or resist their removal.[40]

These instructions are reflected in a document produced by the Dutch authorities and used in training sessions for “escort leaders” organised by Frontex. This says that a minimum of two escorts are needed per deportee, but there are “various criteria” that should be taken into account – for example, the route being taken and the airline being used. For the risk assessment of each individual, “all information collected and available in the ‘chain’ could be useful”. This includes contact details of people responsible for the deportee, any criminal background, any “asylum history”, medical information, length (presumably meaning height), weight, luggage, money, “behaviour of the returnee in all stages” and “behaviour during previous return attempts.” A separate presentation put together by Frontex runs through much the same list but adds “religious and cultural aspects” and language to the factors to be taken into account. The same document also states that the number of escorts assigned to each returnee depends on the risk assessment, rather than proposing a default of two for each individual.[41]

The idea of individualised risk assessment is based on the idea that only the absolute minimum amount of coercion should be applied to individuals, in a proportionate manner, and only when strictly necessary. The UK formally maintains a “presumption against the use of restraint equipment,” but whether this presumption is respected has been questioned – in 335 cases out of 447 in which some type of restraining equipment was used in deportations from the UK between April 2018 and March 2019, “more than one form of restraint was used at the same time.” Such equipment is predominantly deployed on charter flights.[42]

Figure 13: A slide from a Frontex training presentation on the different phases of a forced removal operation

Figure 13: A slide from a Frontex training presentation on the different phases of a forced removal operation

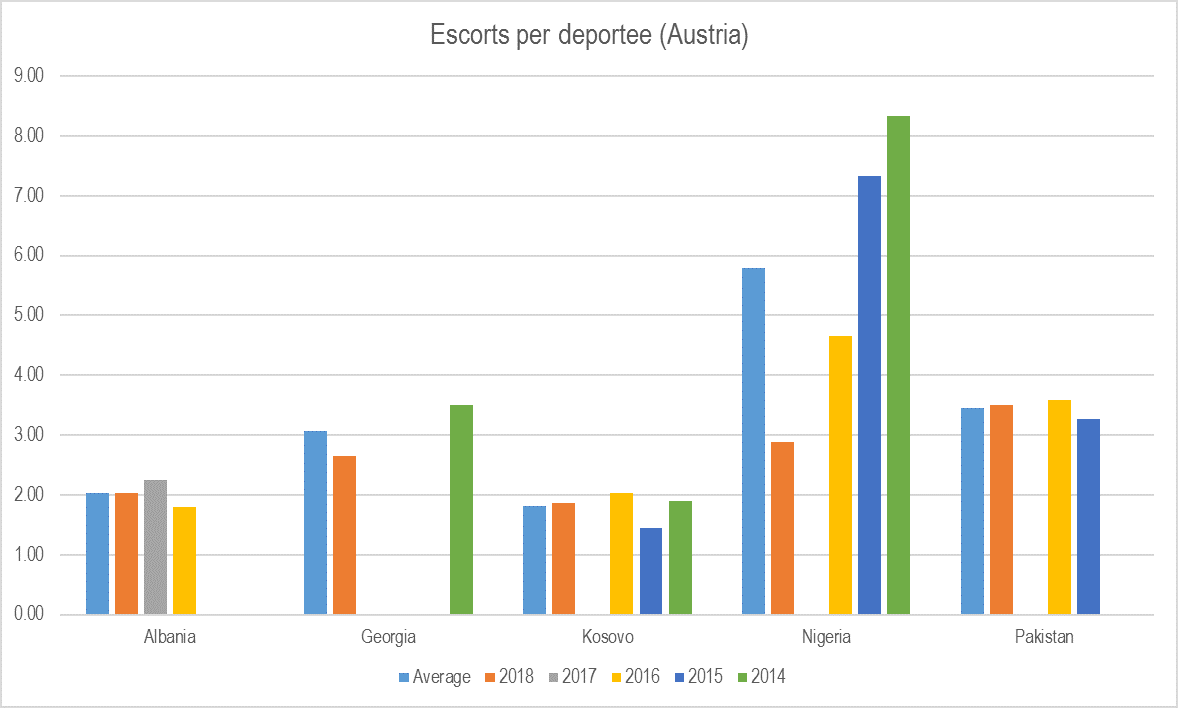

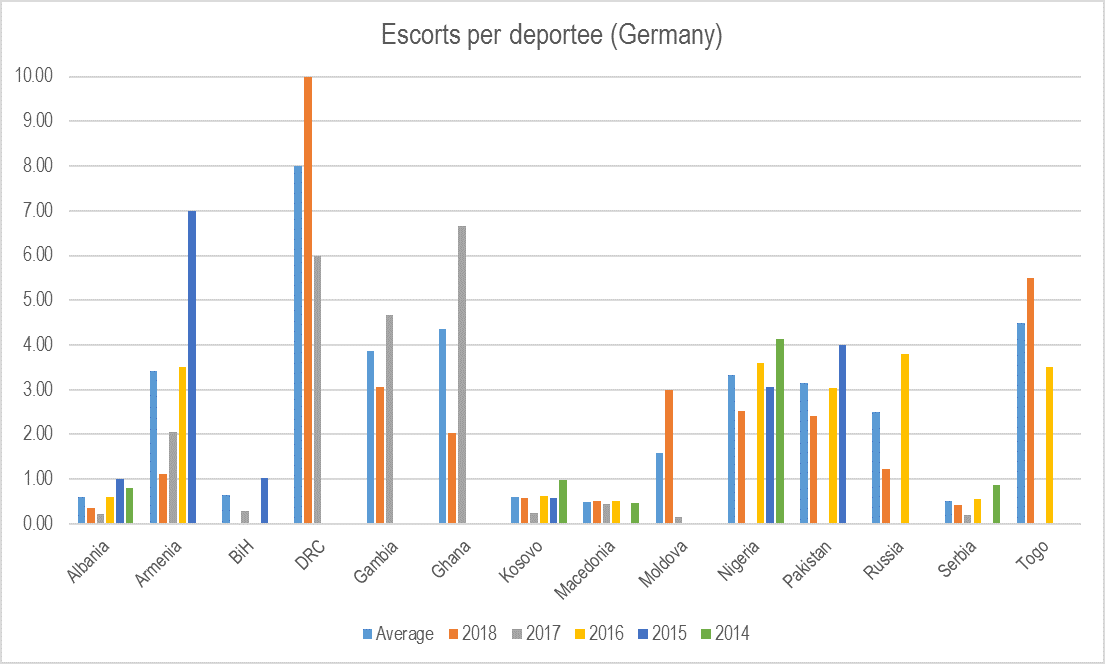

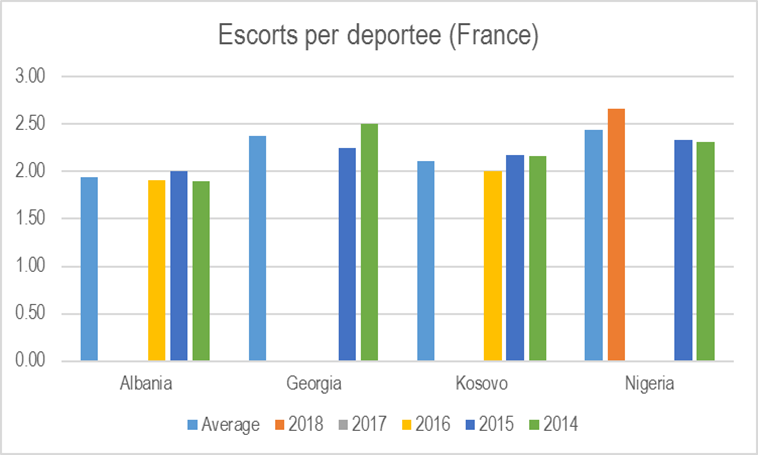

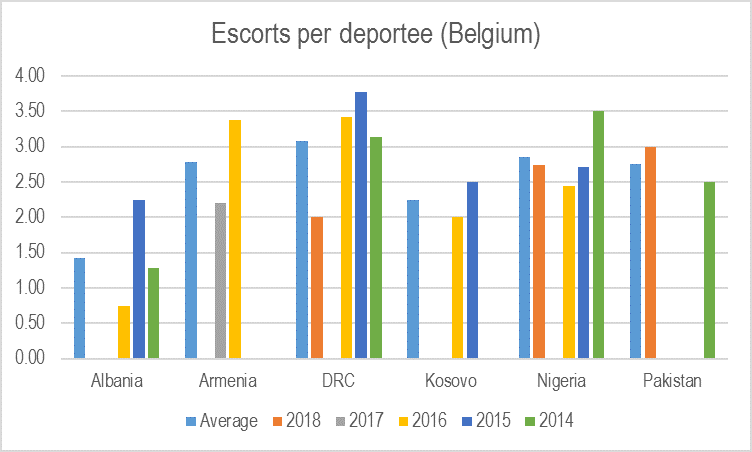

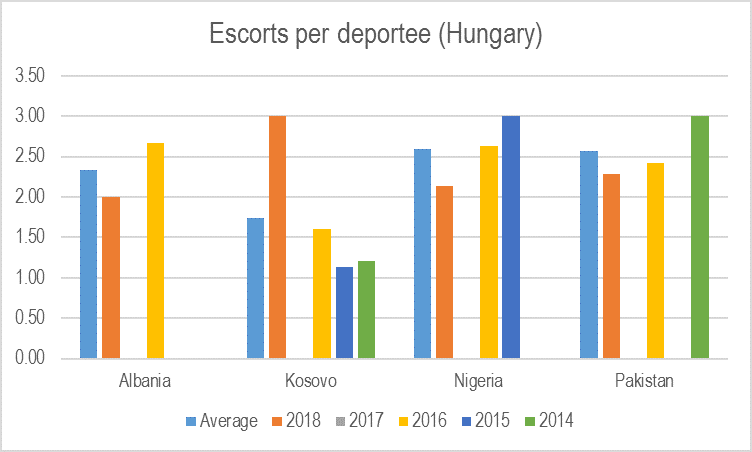

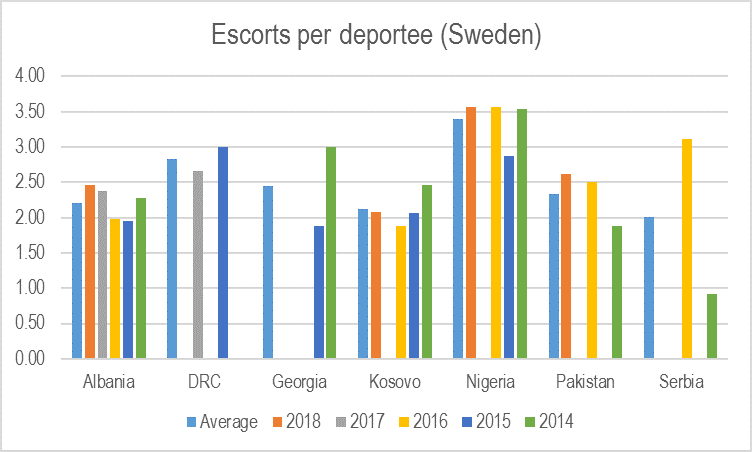

The data available on Frontex-coordinated removal operations, although limited, makes it possible to take a further step back and examine some of the results of risk assessment procedures across different member states. Specifically, it is possible to examine the number of escorts deployed by national authorities per deportee, according to the nationality of those people.[43] The results are, in some cases, striking. They suggest that the risk assessment processes used by national authorities in four different states generally result in people of colour – that is, those being removed to states in Africa, the Middle East and Asia – being accompanied by a greater number of escorts than individuals facing expulsion to states where the majority of the population would generally be considered as ethnically ‘white’.

In the case of Germany, individuals being deported to Balkan states are almost invariably accompanied by far fewer escorts per deportee than people being expelled to states such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria and Pakistan. Less data is available from Austria, Sweden and Belgium, but here a similar (if less-pronounced) pattern emerges. The data from France and Hungary, meanwhile, paints a more nuanced picture.

Of course, it may be that people of certain nationalities are more likely to resist their removal. The CPT has stated:

“Removal operations by air to Nigeria are considered by many national authorities in Europe as the most difficult return operations to be carried out (i.e. difficulties both before and during the flight, at disembarkation, etc.). This conclusion is in particular shared by many national escort teams in Europe and by the relevant independent monitors.” [44]

Talking to Statewatch, a deportation monitor working in Germany also expressed this view, noting that people being removed to countries further from the EU often have a lot more to lose by being expelled. At the same time, she highlighted that it often seems restraints are applied to people unnecessarily. Without more detailed investigations and a more extensive set of data it is not possible to draw any firm conclusions about the patterns that emerge from the data. Nevertheless, they give the impression of concerning practices.

Figure 14: Escorts per deportee (Austria, 2014-18)

Figure 15: Escorts per deportee (Germany, 2014-18)#

Figure 16: Escorts per deportee (France, 2014-18)

Figure 17: Escorts per deportee (Belgium, 2014-18)

Figure 18: Escorts per deportee (Hungary, 2014-18)

Figure 19: Escorts per deportee (Sweden), 2014-18

Monitoring forced removals

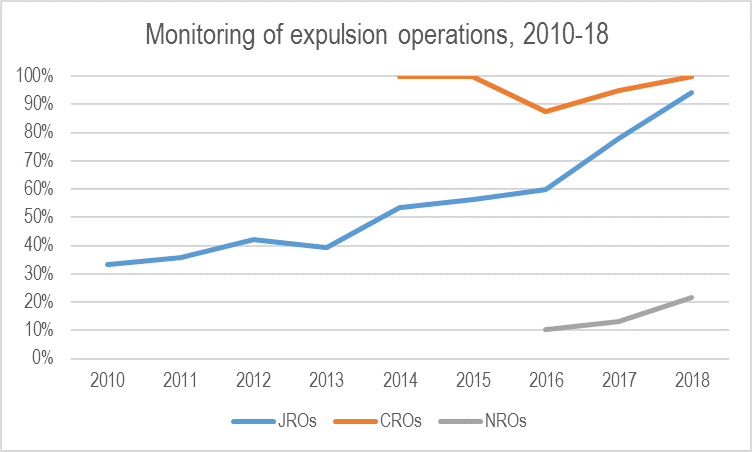

Figure 20: Monitoring of expulsion operations, 2010-18

The deployment of monitors is key to ensuring that individuals are not physically abused or otherwise mistreated during deportation operations. An increase in the use of deportation charter flights by states in the 1990s and 2000s led to corresponding concerns from jurists, scholars, journalists and NGOs that abuses could take place unseen by the outside world. The only other passengers on the plane are the crew and the officials deployed by states: “Since charter flights take place away from the watching eye of the fellow passenger they place detainees in a particularly vulnerable position, outnumbered as they are by the security and escort teams.”[45] Recognition of this problem led to growing calls for the establishment of independent monitoring systems, and in 2008 the EU Returns Directive introduced an obligation for member states to “provide for an effective forced-return monitoring system.”[46]

The Directive provides no further clarity on what precisely this means, but generally, member states identify and appoint independent forced return monitors able to observe and report on all aspects of forced removals, short of what happens after an individual has been disembarked in the destination country. An overview of forced return monitoring systems in the member states published by the EU’s Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) in June 2019 identified four member states – Cyprus, Germany, Slovakia and Sweden – that still lacked an effective forced return monitoring system. Cyprus had no system in place, while in the other three states the monitoring body was part of the same state institution responsible for expulsion operations, and thus lacking in independence.[47] However, the FRA noted that “two of these [states] were taking steps to have effective monitoring systems by 2019,” although it did not identify them.[48]

Following the Ombudsman’s inquiry in 2015, Frontex agreed that the presence of monitors on all removal flights was necessary. However, it noted that while the Returns Directive does require a forced return monitoring system in every member state it “does not imply an obligation to monitor each removal operation.” Furthermore, said the agency, it had no power to direct the activities of national monitoring bodies and so “is not the decision maker on whether there is or is not a monitor present”. Nevertheless, engagement with national authorities had led to an increase in the number of flights monitored and, as the chart below shows, this has improved in the years since. However, the number of NROs with a monitor present remains extremely low – in 2018, only 22% of NROs were monitored, according to data provided by Frontex and analysed for this report.[49]

The Ombudsman also proposed that the JRO Implementation Plan include a requirement for monitors’ reports to be forwarded to Frontex. Frontex agreed with the idea and said that it “would like to see those reports,” but “the national forced-return monitoring bodies are independent and Frontex does not have decisive influence on their activities”. While “monitors contribute with their findings to the OMS Final Return Operation Report… only a few national monitoring bodies have so far provided their complete reports directly to Frontex.”

Starting in 2018, the agency began publishing a six-monthly report summing up the results of all types of return operation and highlighting new developments,[50] although the level of detail in these reports is rather limited. Fundamental rights monitoring and serious incident reporting are given slightly more attention in the report for the latter half of 2018, though it does not refer to the biannual report issued by Frontex’s own Fundamental Rights Office (FRO) covering the same period or acknowledge this report’s concern for the low number of serious incident reports filed compared to the incidents logged in forced return monitors’ reports to the FRO.[51]

Figure 21: The process of setting up a Frontex-coordinated removal operation

Figure 21: The process of setting up a Frontex-coordinated removal operation

The FRO and the requirement to produce reports on forced return operations were both introduced by the 2016 Regulation, which significantly changed the legal basis in force at the time the Ombudsman’s report was issued. It introduced an obligation to constitute a pool of forced-return monitors, drawn from national authorities, who would be invited to monitor Frontex-coordinated expulsion operations. It became active in January 2017. Prior to this, monitors could only be deployed when made available by national authorities for any given operation.

The ‘pool’ monitors conduct their work only on behalf of the member state that has requested their presence – that is, the member state organising any given operation that is coordinated by Frontex (this issue was also raised in submissions to the Ombudsman’s inquiry[52]). They do however report to Frontex, submitting operation reports to the fundamental rights officer. When the 2019 Regulation enters into force, the pool will remain in place, but it will also be possible for Frontex staff to act as monitors. The agency is obliged to appoint 40 fundamental rights officers within the first year of the Regulation’s entry into force, and they will be assigned by the FRO either to particular operations or to the pool by the FRO.[53] A ‘roadmap’ produced by the agency and the European Commission outlines a plan to recruit “at least 40 Fundamental Rights Monitors” who will be provided with “enhanced fundamental rights training” by the last quarter of 2020.[54]

While this may make it possible to monitor a greater number of flights, the independence of the structure is questionable. Frontex funds and manages the pool of forced return monitors, provides training[55] and even selects the individual monitors who will attend operations.[56] Given that the entire process and activity is managed by the agency itself, it is doubtful whether the system can be truly independent. Indeed, the EU’s Fundamental Rights Agency has recommended that an independent actor, rather than Frontex, manages the pool of forced-return monitors.[57] The Council of Europe Committee for the Prevention of Torture has also concluded that “current arrangements cannot be considered as an independent external monitoring mechanism”.[58]

The process of monitoring an individual operation ends with the submission of a report from the monitor to the executive director, the fundamental rights officer and the competent national authorities after the handing over of deportees to third country authorities. Following this, “if necessary, appropriate follow-up shall be ensured by the executive director and competent national authorities respectively”, including further communication (at the discretion of the executive director) with member states and the European Commission.[59] Monitors themselves do not necessarily receive any specific response to the reports they have submitted, seeing only a summary of outcomes, recommendations and “best practices” in the fundamental rights office’s biannual observations. They cannot identify any specific response to incidents reported or recommendations made, how specific member states have responded to breaches, or what measures have been implemented to improve fundamental rights compliance in return operations.

It is extraordinary that despite longstanding, formal recognition of the link between forced removals and violence or mistreatment, the monitoring systems and reporting mechanisms that have rightfully been introduced have not been coupled with effective regimes of accountability. Of course, it must be recognised that these systems and mechanisms in some ways serve to legitimise coercive state practices, and that legitimacy may be called into question if effective accountability regimes were also part of the equation. As the following section demonstrates, shortcomings may also be found in another of the accountability mechanisms that Frontex has been obliged to introduce in recent years – a complaints mechanism for those affected by its operations.

The complaints mechanism: improved but insufficient

While the deployment of monitors can play an important role in preventing fundamental rights abuses during forced removals and preventing them occurring again in the future, the need for other accountability mechanisms with regard to Frontex’s role in deportations has long-been recognised. In 2013, the European Ombudsman called for the establishment of a complaints mechanism. Frontex rebuffed the suggestion, arguing that rights violations were the responsibility of the member states involved in an operation;[60] the Ombudsman raised the issue again in 2015.[61] The 2016 Frontex Regulation introduced a binding obligation on the agency to set up a complaints mechanism and the 2019 Regulation adds further provisions. These provide some improvements, but it is still not possible to consider the agency’s complaints mechanism as truly independent or effective.

A 2018 study published by the Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) provided a systematic examination of regional, international, and supranational human rights law and set out the minimum standards that could qualify a complaints mechanism as an effective remedy.[62] These include institutional independence, accessibility in practice, adequate capacity to conduct thorough and prompt investigations based on evidence, and a suspensive effect in the context of joint expulsions.[63]

For a remedy to be considered institutionally independent, the procedure needs to be impartial.[64] Furthermore, “if complaints are only allowed before the same authority responsible for conducting checks at the EU borders”, it must be possible to appeal the decisions made by that authority.[65] The criterion of accessibility requires adequate access to information, procedural clarity and fairness, respect for privacy and confidentiality, the possibility for returnees to file a complaint “either immediately upon arrival or on board the plane prior to arrival.” The mechanism must also be open to all persons concerned – not only the affected individual(s), but also the responsible supervisory authorities and anyone aware of the violation (for example, journalists or NGOs).[66] Finally, thorough and prompt investigations require adequate capacity in both procedural and practical terms – a “genuine complaints mechanism” must be based on transparent procedures, the exclusion of large margins of appreciation[67] and thoroughness in follow-up procedures.[68] With the changes introduced by the 2019 Regulation, Frontex’s complaints mechanism has come some way towards meeting these criteria. Nevertheless, there are still significant shortcomings.[69]

The 2019 Regulation gives the fundamental rights officer (who reports directly to the agency’s management board, rather than the executive director, and must be able to act autonomously and independently[70]) an expanded role in the complaints procedure. They will now have a greater say in determining the admissibility of complaints, in ensuring that the agency and the member states follow up on complaints concerning their staff, and in recommending to the executive director the action to be taken in response to complaints (including “referral for the initiation of civil or criminal justice proceedings,” where deemed appropriate).

Nevertheless, institutional independence is still sorely lacking – it remains the job of the executive director to “ensure the appropriate follow-up” to complaints accepted and registered by the fundamental rights officer. There is no mention in the Regulation of the possibility to appeal against decisions.

The 2019 Regulation takes some steps to make the complaints mechanism more accessible. Under the 2016 rules, individuals could submit a complaint if they considered that the actions of staff involved in the agency’s operational activities[71] had breached their fundamental rights. Now, complaints may also be submitted in relation to a failure to act by Frontex or member state officials. Furthermore, the onus to complain is not only on the affected individual – since 2016, it has been possible for complaints to be submitted by any party representing the affected individual.[72]

New provisions also require that the standardised complaint form “be easily accessible, including on mobile devices,” and Frontex is obliged to provide “further guidance and assistance” to complainants.[73] Complainants must be given information on the registration and assessment of their complaint and informed when a decision is made on its admissibility. An “appropriate procedure” must be established for inadmissible or unfounded complaints, which must be re-assessed where new evidence is submitted. Any decision on a complaint must also be provided in written form that states the reasons for the decision.[74] Complaints are treated confidentially unless the complainant explicitly states otherwise.[75] Furthermore, the implementation of the complaints mechanism should become more transparent when the 2019 Regulation enters into force – the FRO’s annual report must now include “specific references to the Agency’s and Member States’ findings and the follow-up to complaints.”[76]

The low number of submitted complaints has raised questions regarding the accessibility of the remedy. Carrera and Stefan indicate that only two complaints were registered in 2016, and 13 in 2017.[77] They have also noted that complaints must be signed (that is, they cannot be anonymous) and the complaint must be submitted in writing, while the admissibility criteria do not seem to take into account the practical difficulties individuals in an irregular situation may face in accessing justice, especially when the individual has been subject to deportation. Nevertheless, the overall accessibility of the complaints procedure has clearly been improved – on paper. The question is whether they will be put into practice effectively. Current practices show a clear need for improvements – it has been reported that deportees are not always provided with complaint forms, despite the fact that a member of Frontex staff is present on every Frontex-coordinated expulsion flight.[78]

Finally, an effective complaints mechanism requires thorough and prompt investigations. As noted above, it remains the executive director’s responsibility to examine the complaint, reach “a preliminary view” and ensure “appropriate follow-up”, if considered necessary.[79] Without further details on the handling of complaints received by the agency so far, it is hard to evaluate whether this can be considered a “thorough” investigation. However, there is now a requirement for the fundamental rights officer to recommend the appropriate course of action on any given complaint, which reduces the executive director’s margin of appreciation.[80] In the case of complaints directed to national authorities, the thoroughness of any given investigation is dependent on the legislation and practice in the member states. Complaints concerning members of Frontex teams (rather than the agency’s own staff) must be forwarded to national authorities and fundamental rights bodies, “for further action in accordance with their mandate.”[81]

There is no clear requirement for investigations to be prompt. Complainants must be informed that “a response may be expected as soon as it becomes available,” but there are no further details on time limits. Nor is there any limit on how long the executive director may take in reaching their decision. There is a requirement for the executive director to provide a report to the fundamental rights officer on follow-up within a “determined timeframe”, but both the legislation and the implementing rules are silent as to what that timeframe is.

One overarching issue for an effective complaints mechanism is the provision of sufficient staff and resources to the fundamental rights officer. As the European Parliament highlighted in April 2018, “the fundamental rights officer has received five new posts since 2016”. However, at that time, three remained vacant – a situation that the Parliament “deeply deplored.”[82] The situation had not improved significantly by the end of the year, when the Consultative Forum warned that the Fundamental Rights Office’s work was still “compromised in areas such as monitoring of operations, handling of complaints, provision of advice on training, risk analysis, third country cooperation and return activities.”[83]

The Consultative Forum’s 2018 report noted that new rules on the complaint mechanism had been drafted by the fundamental rights officer. These were a “remarkable improvement” on the existing rules, but had not been adopted. When the 2019 Regulation comes into force it will be necessary for the agency to adopt new implementing rules, providing an opportunity to address several issues relevant to the complaints mechanism. Nevertheless, although the 2019 Regulation has introduced an explicit requirement that the complaints mechanism be “independent and effective”,[84] the legislation governing it does not meet these requirements. There is still no truly effective remedy available to individuals who have had their fundamental rights violated by Frontex staff or agents – and even the insufficient rules that do exist cannot be properly implemented if the staff and resources for doing so are not available.

"Regaining control": new powers for Frontex

Conclusions

[1] It is unknown whether this was a Frontex-coordinated flight. However, the agency’s data shows that Italy was the organising member state for two flights to Nigeria around that time, on 26 January and 23 February. The interior ministry’s memo made said that 50 places for women were being made available in Rome and 45 for men would be distributed between Turin (25) Brindisi (10) and Caltanissetta (10), from 26 January to 18 February 2017. The note said the places must be made available "without exceptions", even if it meant releasing other occupants ahead of schedule.

[2] Italy: Police instructed to target Nigerians – There’s a charter plane to fill and interviews with Nigerian authorities have already been agreed, Statewatch News Online, 2 January 2017, http://www.statewatch.org/news/2017/feb/italy-nigeria.htm

[3] Ibid. A further report on an incident in Italy in which “two women were repatriated, despite the suspension of their deportation decreed by the court,” is available here: Yasha Maccanico, ‘Italy: Mass discrimination based on nationality and human rights violations – Nigerian refugees and trafficking victims deported from Rome’, Statewatch Analysis, March 2016, http://www.statewatch.org/analyses/no-287-italy-mass-discrimination.pdf

[4] European Court of Human Rights, ‘Collective expulsion of aliens’, July 2019, https://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/FS_Collective_expulsions_ENG.pdf

[5] ‘EU-Turkey statement, 18 March 2016’, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/03/18/eu-turkey-statement/

[6] Amnesty International, ‘Greece: Evidence points to illegal forced returns of Syrian refugees to Turkey’, 28 October 2016, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2016/10/greece-evidence-points-to-illegal-forced-returns-of-syrian-refugees-to-turkey/

[7] Migreurop, ‘New Group Deportation Flight Coordinated by FRONTEX as means of Collective Expulsion towards Serbia: Rights violation and the impunity of member-states’, 20 April 2012, http://www.migreurop.org/article2113.html?lang=en

[8] Bill Frelick, ‘Déjà vu on the Greek-Turkey border’, Human Rights Watch, 20 December 2018, https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/12/20/deja-vu-greek-turkey-border

[9] ‘Greece – 2018 update’, Asylum Information Database, https://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/greece

[10] European Ombudsman, ‘Decision in case 735/2017/MDC on the European Asylum Support Office’s’ (EASO) involvement in the decision-making process concerning admissibility of applications for international protection submitted in the Greek Hotspots, in particular shortcomings in admissibility interviews’, 5 July 2018, https://www.ombudsman.europa.eu/en/decision/en/98711. See also: FRA, ‘Update of the 2016 Opinion of the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights on fundamental rights in the ‘hotspots’ set up in Greece and Italy’, February 2019, https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2019-opinion-hotspots-update-03-2019_en.pdf

[11] Elliott Douglas, ‘Greece illegally deported 60,000 migrants to Turkey: report’, DW, 4 November 2019, https://www.dw.com/en/greece-illegally-deported-60000-migrants-to-turkey-report/a-51234698

[12] The Greek Ombudsman, ‘Return of Third Country Nationals’, pp.24-25, https://www.synigoros.gr/resources/docs/english-final.pdf

[13] For example, in 2017 the recognition rate for asylum applicants from Iraq was 8% in Denmark and 86% in France; for people from Afghanistan the recognition rate was 35% in the UK but 75% in Greece; and for Ethiopian applicants the rate was 37% in Sweden but 92% in Italy. There are numerous other examples. See: ‘Asylum Recognition Rates in the EU/EFTA by Country, 2008-2017’, Migration Policy Institute, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/asylum-recognition-rates-euefta-country-2008-2017

[14] M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece, para. 301, http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-103050

[15] Such concerns have been expressed, for instance, also with respect to Hungary (Hungarian Helsinki Committee, ‘Serbia as a safe third country: Revisited’, 2012, http://helsinki.hu/wp-content/uploads/Serbia-report-final.pdf) and Germany (see footnote 279).

[16] ‘Immigration Detention in Bulgaria: Fewer Migrants and Refugees, More Fences’, Global Detention Project, 29 April 2019, https://www.globaldetentionproject.org/immigration-detention-bulgaria-fewer-migrants-refugees-fences

[17] A report on a joint return operation that departed from the Netherlands raised concerns regarding access to a lawyer, medical examinations and the possibility for deportees to make phone calls to their relatives prior to removal. Similar issues were raised in relation to an inspection of a deportation from Spain, as well as the fact that the individuals being expelled were notified just 12 hours before their removal. Because of the lack of time given to prepare for removal a number of deportees were unable to withdraw money from their Spanish bank accounts, and one man was even deported in his work uniform. See: ‘Report to the Government of the Netherlands’, CPT/Inf(2015) 14, 5 February 2015, https://rm.coe.int/168069782c; ‘Report to the Spanish Government’, CPT/Inf(2016) 35, 15 December 2016, https://rm.coe.int/16806ce534

[18] ‘'Inhumane' Frontex forced returns going unreported’, EUobserver, 30 September 2019, https://euobserver.com/migration/146090

[19] ‘EU agency kept in dark on forced flight abuse’, 9 October 2019, https://euobserver.com/migration/146203

[20] ‘'Inhumane' Frontex forced returns going unreported’, EUobserver, 30 September 2019, https://euobserver.com/migration/146090

[21] ‘Report to the Italian Government’, CPT/Inf (2016) 33, p.9, https://rm.coe.int/16806ce532

[22] ‘Hungary’s coerced removal of Afghan families deeply shocking – UNHCR’, UNHCR, 8 May 2019, https://www.unhcr.org/ceu/10940-hungarys-coerced-removal-of-afghan-families-deeply-shocking-unhcr.html

[23] Tineke Strik, ‘Pushback policies and practices in Council of Europe member states’, http://website-pace.net/documents/19863/5680684/20190531-PushbackPolicies-EN.pdf/4ecacee9-6c04-4202-a555-0eed58299b63. In May 2017 the Commission took the first step in infringement proceedings against Hungary for its violation of asylum-seekers’ rights – but it was doing so for the second time. It is only recently that it has gone a step further and sent a ‘reasoned opinion’, the step in the process before the initiation of a case before the CJEU. See: ‘HUNGARY: Commission takes next step in the infringement procedure for non-provision of food in transit zones’, European Commission, 10 October 2019, https://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_INF-19-5950_EN.htm; and ‘Commission takes first steps against Hungarian asylum law - for the second time’, Statewatch News, 17 May 2017, http://www.statewatch.org/news/2017/may/eu-com-hungary-asylum.htm.

[24] ‘Post-Deportation Monitoring Network - Suggested Reading List’, Rights in Exile, http://www.refugeelegalaidinformation.org/post-deportation-monitoring-network-suggested-reading-list

[25] May Bulman, ‘Afghan father who sought refuge in UK 'shot dead by Taliban' after being deported by Home Office’, The Independent, 13 September 2018, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/zainadin-fazlie-deport-home-office-taliban-afghanistan-shot-dead-refugee-a8536736.html

[26] ‘Post deportation monitoring’, Rights in Exile, http://www.refugeelegalaidinformation.org/post-deportation-monitoring

[27] UNHCR, ’Hungary’s coerced removal of Afghan families deeply shocking’, 8 May 2019, https://www.unhcr.org/ceu/10940-hungarys-coerced-removal-of-afghan-families-deeply-shocking-unhcr.html

[28] HIAS, Islamic Relief USA, ‘EASO’s Operation on the Greek Hotspots An overlooked consequence of the EU-Turkey Deal Greece Refugee Rights Initiative’, March 2018, https://www.hias.org/sites/default/files/hias_greece_report_easo.pdf; EU Ombudsman, Decision in case 735/2017/MDC on the European Asylum Support Office’s’ (EASO) involvement in the decision-making process concerning admissibility of applications for international protection submitted in the Greek Hotspots, in particular shortcomings in admissibility interviews, July 2018, https://www.ombudsman.europa.eu/nl/decision/en/98711.

[29] Vaughne Miller, ‘Taking a complaint to the Court of Justice of the European Union’, 11 March 2010, https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN05397/SN05397.pdf; ‘Complaints to the European Court of Justice’, Eurofound, 20 September 2011, https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/observatories/eurwork/industrial-relations-dictionary/complaints-to-the-european-court-of-justice

[30] Council of Europe, ‘EU accession to the ECHR’, undated, https://www.coe.int/en/web/human-rights-intergovernmental-cooperation/accession-of-the-european-union-to-the-european-convention-on-human-rights; European Parliament Think Tank, ‘ EU accession to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)’, 6 July 2017, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/da/document.html?reference=EPRS_BRI%282017%29607298

[31] Decision of the European Ombudsman closing her own-initiative inquiry OI/9/2014/MHZ concerning the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union (Frontex), para. 37, 4 May 2015, https://www.ombudsman.europa.eu/en/decision/en/59740

[32] UNITED continues to compile a list of deaths of people who have died due to “the restrictive policies of ‘Fortress Europe’”. See: ‘The Fatal Policies of Fortress Europe’, http://www.unitedagainstracism.org/campaigns/refugee-campaign/fortress-europe/

[33] Frontex, ‘Guide for Joint Return Operations by Air coordinated by Frontex’, 9 June 2016, https://frontex.europa.eu/publications/guide-for-joint-return-operations-by-air-coordinated-by-frontex-PkKeDV

[34] Frontex, ‘Fundamental Rights in return operations’, undated, http://statewatch.org/docbin/eu-frontex-deportation-fro-return-specialists-training-11-17.pdf

[35] Restraint techniques that can cause positional asphyxia are, however, covered in training sessions for escorts organised by the agency. See, for example: Frontex, ‘National training Athens18/3/2019-22/3/2019’, http://statewatch.org/docbin/eu-frontex-deportations-training-agenda-athens-3-19.pdf

[36] Clara Lecadet, ‘Deportation, nation state, capital: Between legitimisation and violence’, Radical Philosophy, December 2018, https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/article/deportation-nation-state-capital

[37] Section 1.2.6, ‘Arrangements regarding the number of escorts’, cited in European Commission, ‘Return Handbook’, undated, p.43, https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/proposal-implementation-package/docs/return_handbook_en.pdf

[38] Section 6.1.16, ‘Risk assessment’, in Frontex, ‘Guide for Joint Returns Operations by Air coordinated by Frontex’, 12 May 2016, https://frontex.europa.eu/assets/Publications/General/Guide_for_Joint_Return_Operations_by_Air_coordinated_by_Frontex.pdf

[39] Home Office, ‘Use of restraint(s) for escorted moves – all staff’, Detention Services Order 07/2016, August 2016, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/543806/DSO_07-2016_Use_of_Restraints.pdf

[40] European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT), ‘Report to the German government on the visit to Germany from 13 to 15 August 2019’, CPT/Inf (2019) 14, p.17, https://rm.coe.int/1680945a2d

[41] Frontex, ‘Organisation of a RO – Pre return phase’, undated, http://statewatch.org/docbin/eu-frontex-deportations-organisation-of-ro.pdf

[42] Diane Taylor, ‘Shackles and restraints used on hundreds of deportees from UK’, The Guardian, 11 August 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2019/aug/11/shackles-and-restraints-used-on-hundreds-of-deportees-from-uk

[43] The data used here concerns those joint removal operations for which data was available on the number of escorts deployed per deportee for each destination (thus excluding, for example, flights with two destinations where the number of escorts was not disaggregated by destination). Charts have been produced for member states with data on at least four destination states over at least two years. It is assumed that the nationality of the individuals being deported is that of the country to which they are being removed, although this may not always be the case.

[44] ‘Report to the Government of the Netherlands’, CPT/Inf(2015) 14, 5 February 2015, p.7, https://rm.coe.int/168069782c

[45] William Walters, ‘The Microphysics of Deportation. A Critical Reading of Return Flight Monitoring Reports’ in Matthias Hoesch and Lena Laube (eds.), Proceedings of the 2018 ZiF Workshop: Studying Migration Policies at the Interface between Empirical Research and Normative Analysis, ULB Münster, 2019, pp.166-186

[46] Directive 2008/115/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on common standards and procedures in Member States for returning illegally staying third-country nationals, article 8(6)

[47] FRA, ‘Effective forced return monitoring systems 2018’, https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/forced_return_monitoring_overview_2018_en.pdf

[48] FRA, ‘Forced return monitoring systems - 2019 update’, June 2019, https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2019/forced-return-monitoring-systems-2019-update

[49] In an evaluation of return operations carried out in the first half of 2018, Frontex said: “it has to be highlighted that the number of NROs physically monitored referred only to operations where a national monitor was also on board. The other 24 return operations in which only one Member State returned non-EU country nationals are considered joint operations because of the presence of a monitor from the Frontex pool, provided by another Member State.” In any case, it is clear that national authorities are clearly failing to meet the highest standards when it comes to monitoring forced return operations.

[50] In accordance with Article 28(8) of the 2016 Regulation, now Article 51(6) in the 2019 Regulation.

[51] FRO biannual report, report-frontex-document-104.pdf

[52] “With regard to so-called "representative monitoring" under Article 14(5) of the Code, the Ombudsman notes some respondents' scepticism as to how a monitor from one Member State could monitor the behaviour of escorts from another Member State, given that they act according to their national rules. The Ombudsman, however, sees potential in such monitoring, provided that monitors are properly briefed on the means of restraint agreed in the Implementation Plan.” See: ‘Decision of the European Ombudsman’, para. 41, https://www.ombudsman.europa.eu/en/decision/en/59740 s

[53] Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the European Border and Coast Guard and repealing Regulation (EU) n° 1052/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Regulation (EU) n° 2016/1624 of the European Parliament and of the Council, article 107(a), (1)(a), (2)(a), (2)(v)(b), (3), (4).

[54] ‘'Roadmap' for implementing new Frontex Regulation: full steam ahead’, Statewatch News, 25 November 2019, http://www.statewatch.org/news/2019/nov/eu-frontex-roadmap.htm

[55] After undertaking studies for the European Commission on the monitoring of forced removals, the International Centre for Migration Policy Development was then contracted to implement three FReM (Forced Returns Monitoring) projects. FReM I ran from 2013-15 and was co-funded by the European Return Fund. A new, €1.1 million FReM II project was launched to complement the 2016 upgrade to Frontex’s mandate. A third iteration of the project is due to be handed over to Frontex. The agency has been closely involved with the FReM projects “since day one”, according to ICMPD staff responsible for the project, and they do not think much will change following the handover.

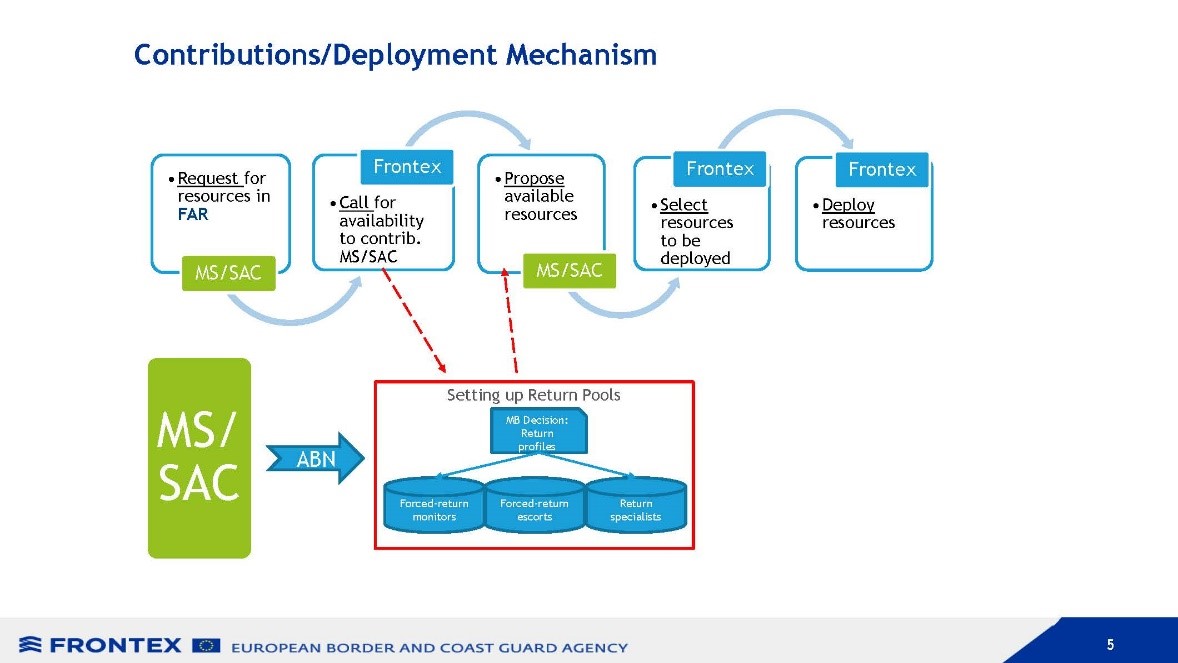

[56] To request a monitor on an operation, member states or Schengen Associated Countries (MSSAC) submit a call to the ECRet, via the FAR, specifying any additional eligibility criteria (for instance, experience in cooperation or working with Frontex, or knowledge of languages spoken in countries of destination of the return operation). The Pooled Resources Unit of Frontex then puts out an open call to all MSSAC who contribute to the Frontex forced-return monitors pool. Any experts offered by these competent authorities must be members of the pool, and must have received the standard FReM training from Frontex, the ICMPD and the FRA. Once Frontex receives the request from a MSSAC for resources, Frontex puts out a call for availability to contributing MSSAC. Based on the proposed candidates from the states’ competent authorities, Frontex then select and deploy monitors to return operations.

[57] Fundamental Rights Agency, ‘The revised European Border and Coast Guard Agency and its fundamental rights implications’, 2018, https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2018-opinion-ebcg-05-2018_en.pdf

[58] ‘Report to the German government on the visit to Germany carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment from 13 to 15 August 2018’, CPT/Inf (2019) 14, 9 May 2019, p.24, https://rm.coe.int/1680945a2d

[59] Article 52(5a)

[60] European Ombudsman, ‘Ombudsman calls on Frontex to deal with complaints about fundamental rights infringements’, 13 November 2013, https://www.ombudsman.europa.eu/en/press-release/en/52487

[61] In this case, however, there was no mention of a complaints mechanism, but rather a call for the provision of a standardised complaint form to deportees.

[62] Sergio Carrera and Marco Stefan, ‘Complaint Mechanisms in Border Management and Expulsion Operations in Europe: Effective Remedies for Victims of Human Rights Violations?’, CEPS, 2018, https://www.ceps.eu/system/files/Complaint%20Mechanisms_A4.pdf

[63] Ibid., p.5

[64] Ibid., p.13

[65] Ibid., p. 36

[66] Ibid., p.13. Such public interest complaints were for the Ombudsman a necessary precondition for an effective complaints mechanism in Frontex operations. See: ‘Draft recommendation of the European Ombudsman in his own-initiative inquiry OI/5/2012/BEH-MHZ concerning the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union (Frontex)’, http://www.ombudsman.europa.eu/en/cases/draftrecommendation.faces/en/49794/html.bookmark.

[67] ‘Complaint Mechanisms in Border Management and Expulsion Operations in Europe: Effective Remedies for Victims of Human Rights Violations?’, p. 24

[68] Ibid., p36

[69] In the case of complaints declared inadmissible or unfounded, however, the agency must now set up “an appropriate procedure” (Article 111(5)).

[70] Articles 109(4) and (5), 2019 Regulation

[71] Specifically, Article 111(2) of the 2019 Regulation lists the following activities in relation to which a complaint may be submitted: “a joint operation, pilot project, rapid border intervention, migration management support team deployment, return operation, return intervention or an operational activity of the Agency in a third country.”

[72] The rules on the complaints mechanism adopted by the executive director in order to implement the 2016 Regulation allow the submission of complaints by “any party, whether a natural or legal person, acting on [the affected individual’s] behalf,” as well as by the individual themselves. See: ‘The agency’s rules on the complaints mechanism’, https://frontex.europa.eu/assets/Key_Documents/Complaints/Annex_1_-_Frontexs_rules_on_the_complaints_mechanism.pdf

[73] Article 111(10), 2019 Regulation

[74] Article 111(5), 2019 Regulation

[75] Article 111(11), 2019 Regulation

[76] Article 111(9), 2019 Regulation

[77] ‘Complaint Mechanisms in Border Management and Expulsion Operations in Europe: Effective Remedies for Victims of Human Rights Violations?’, p. 25

[78] FRO report 2018

[79] Article 10, ‘The agency’s rules on the complaints mechanism’, https://frontex.europa.eu/assets/Key_Documents/Complaints/Annex_1_-_Frontexs_rules_on_the_complaints_mechanism.pdf

[80] Article 111(6), 2019 Regulation: “In the case of a registered complaint concerning a staff member of the Agency, the fundamental rights officer shall recommend appropriate follow-up, including disciplinary measures, to the executive director and, where appropriate, referral for the initiation of civil or criminal justice proceedings in accordance with this Regulation and national law.”

[81] Article 111(4), 2019 Regulation

[82] ‘European Parliament decision of 18 April 2018 on discharge in respect of the implementation of the budget of the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) for the financial year 2016’, para. 17, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2018-0164_EN.html. Frontex’s Consultative Forum on Fundamental Rights has also repeatedly raised this issue, stating in its 2018 report that inadequate staffing is “seriously undermining the fulfilment” of the agency’s fundamental rights obligations. See: ‘NGOs, EU and international agencies sound the alarm over Frontex's respect for fundamental rights’, Statewatch News, 5 March 2019, http://www.statewatch.org/news/2019/mar/fx-consultative-forum-rep.htm

[83] ‘NGOs, EU and international agencies sound the alarm over Frontex's respect for fundamental rights’, Statewatch News, 5 March 2019, http://www.statewatch.org/news/2019/mar/fx-consultative-forum-rep.htm

[84] Article 111(1), 2019 Regulation

Spotted an error? If you've spotted a problem with this page, just click once to let us know.