EU: Commission halts migration cooperation with Niger, but for how long?

Topic

Country/Region

07 September 2023

EU-promoted migration control policies have caused discontent in Niger, and it has been suggested they may have contributed to the unpopularity of toppled president Mohamed Bazoum, who was ousted in a military coup in July. After the coup, the European Commission halted its support for security and migration projects in the country. However, its willingness to cooperate with institutions and actors that violate human rights elsewhere raises the question: for how long?

Support our work: become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

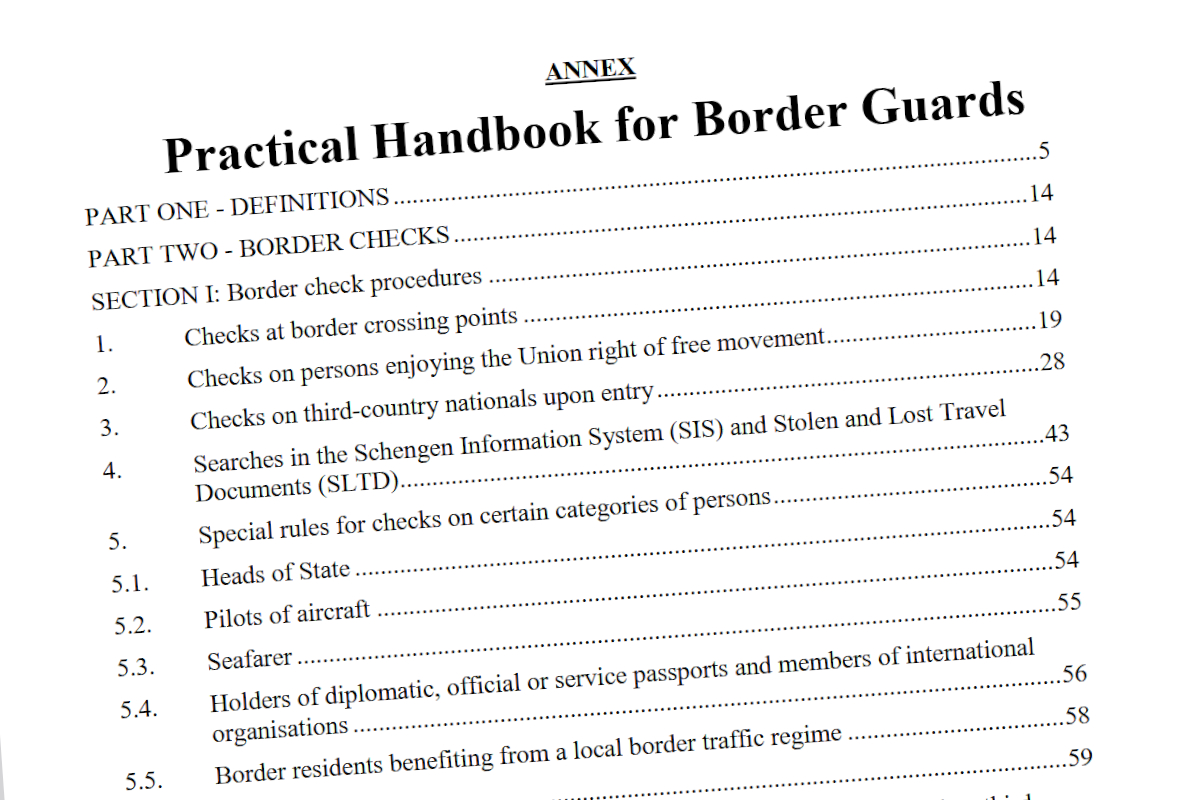

Former EU Migration & Home Affairs Commissioner, Dimitris Avramopoulos, meets then-interior minister of Niger, Mohamed Bazoum, in 2015. Image: Dimitris Avramopoulos, CC BY-SA 2.0

Military takeover

On 26 July, Niger’s presidential guard detained the president, Mohamed Bazoum. They justified their actions by citing a “deteriorating security situation and bad governance.”

Two neighbouring countries, Mali and Burkina Faso, which are also under junta control, backed the military takeover. In response to statements from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) that “force” could be used to restore Niger’s constitutional order, Mali and Burkina Faso announced that any military intervention would be seen as a “declaration of war.”

A week after the putsch, European countries evacuated their citizens and cut off financial assistance to Niger, which has come to play a key role in the EU’s attempts to externalise migration controls – the mayor of Agadez once said that his city and region had “become a laboratory for Europe’s migration policies.”

Niger: key to EU border externalisation policy in Africa

The coup will come as a blow to the politicians and officials who have sought to cultivate Niger as a link in the chain of the EU’s externalised border controls. The European Commission has put its migration and security projects in Niger “on hold for further assessment of their impact,” a spokesperson confirmed to Statewatch, though EU-funded projects run by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) are ongoing.

As far back as 2004, the Commission cultivated contacts with Nigerien authorities to discuss possible cooperation on migration. Nigerien officials highlighted the beneficial aspect of migration into Libya and the economic and social importance for the local population of assisting in the travel of migrants.

EU officials, for their part, suggested that government concern about rebels in Niger’s north and “international concern about possible terrorist links” could be used to “offer a ground for a common understanding of the desirability of control and of addressing the issue of illegal immigration.”

An echo of this approach came 17 years later, following a visit to Niger by a senior EU military official, Esteban Pérez, the Director of the EU’s Civilian Planning and Conduct Capability.

In his report on the visit, he noted that the main strategic challenges highlighted by Nigerien authorities were the state’s lack of reach in remote areas, their lack of investigative capacities, and poor coordination between agencies dealing with crime and terrorism.

An EU official cited by Pérez, meanwhile, considered that “Terrorism, Organised Crime and Illegal Migration constitute the main elements that currently pose a serious threat to the security and stability of the Country.” None of the Nigerien officials cited by Perez mentioned the issue of “illegal migration”.

Shifting mandates, new missions

A lot happened between those two official visits to Niger.

In 2012, the EUCAP Sahel Niger mission was launched with the tasks of reducing insecurity and terrorism, and in 2016 was given a role in combating irregular migration. Some 150 officials from EU member states make up the mission, and in September 2022 it was extended for a further two years and awarded a budget of €72 million.

That extension came two months after the Commission announced a new “operational partnership” on migrant smuggling with Niger, declaring that the EU’s relationship with the country was “moving up a gear, from both an operational and a political point of view.”

In July, Frontex also signed a working arrangement with EUCAP Sahel Niger, as part of a broader plan for the agency to gain a stronger foothold in the country.

As highlighted in the Statewatch report Secrecy and the externalisation of EU migration control, Frontex deployed a liaison officer to Niamey, the Nigerien capital, in 2017, and in 2018 opened a “Risk Analysis Cell” (RAC) in the country. The role of the RAC is “collect and analyse strategic data on cross-border crime in various African countries and support relevant authorities involved in border management,” including by sharing data with Frontex.

These deployments followed the Nigerien government’s adoption of a 2015 law introducing severe penalties, including fines and imprisonment, for involvement in smuggling or trafficking. Subsequently, police and border guards from EU member states started setting up offices in the country and provided training and materials for local authorities, paving the way for Frontex.

Frontex’s report on cooperation with third countries in 2022 notes that its trips to Niger in partnership with European Commission officials had led to “an agreed working arrangement text with Niger.” That arrangement could allow the exchange of personal data between Nigerien authorities and Frontex, as well as other forms of cooperation. When or whether that agreement will be signed, however, is an open question.

Still Europe’s border guard?

Agadez is a town bordering the Sahara whose economy suffered substantially following the criminalization of passeurs under the 2015 law. It also plays host to a US military drone base. In the days following the coup, a demonstration took place there in support of the military and denouncing Western influence in Niger.

Another demonstration on Sunday 20 August in front of the offices of the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) and the United Nations Council for Refugees (UNHCR) called for the law to be repealed.

An article in The Guardian explicitly linked Bazoum’s support for the EU’s migration demands and his subsequent overthrow in a coup:

“Bazoum became interior minister in 2016, the same year the law was implemented. The legislation became known as the ‘Bazoum law’.

(…)

The legislation was opposed by figures in the Nigerien military who had previously benefitted financially from bribes paid by people smugglers and those being smuggled.”

The Guardian quotes a resident of Agadez who noted that it was not just the military that benefited from the previously free movement of people to and from Libya:

“The army officers who used to stand on the checkpoints, the people who drove the migrants, the people who would take migrants into Libya – the whole population used to depend on this business.”

The law itself may be in trouble, however – and not just from a new administration that may not be inclined to continue cooperating with European migration policies.

Back in 2004, the Nigerien authorities warned Commission officials that restrictions on travel for citizens of ECOWAS member states would be illegal – the ECOWAS treaty that grants freedom of circulation across all its members.

A case pending at the ECOWAS Court of Justice is seeking to overturn the Bazoum law, with the complaint emphasising that it has “resulted in the multiplication of violations of freedom of movement in the ECOWAS area over the past six years and has exposed people in transit to violence, abuse and torture.”

On hold… for how long?

The EU has demonstrated a clear willingness to support institutions, groups and governments with scant respect for human rights in order to implement its border externalisation policies.

The UN has accused the EU of aiding crimes against humanity through its support for the Libyan coast guard. An open letter signed by almost 400 academics and members of civil society (including the Director of Statewatch) has accused the EU of “opportunistically and irresponsibly backing the [Tunisian] President’s stances and fueling anti-migrant and anti-Black hatred.” Previous EU support for Sudan saw it equip and empower the notorious Rapid Support Forces paramilitary group, and “reinforce the surveillance capabilities of a Sudanese government that has violently suppressed Sudanese citizens for the past 28 years.”

Meanwhile, the Commission told Statewatch that: “The EU has firmly condemned the coup and called for the restoration of the constitutional order in Niger. We do not recognise those currently in power in Niger.” This is the only logical stance for an institution ostensibly committed to human rights and democratic standards to take – but given the overwhelming political priority given to halting irregular migration, many will be wondering how long that stance can hold.

Our work is only possible with your support.

Become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Further reading

“PUSH BACK FRONTEX”: campaign in Senegal targets deployment of EU border agency

A campaign against the deployment of Frontex in Senegal is seeking to halt a proposed agreement between the EU and the West African state and to denounce “how the EU collaborates with our complicit regimes killing people in the Mediterranean and in transit countries.”

EU border mission in Libya gets revamp

The EU Border Assistance Mission (EUBAM) in Libya is about to receive an update to its tasks. References to supporting institutional reform and cooperation with the UN Support Mission in Libya are to be removed from its mandate. The current budget is to be extended by three months, pending a decision by the Council on funding for the next two years.

Spotted an error? If you've spotted a problem with this page, just click once to let us know.