Prints in politics: cheap, easily replicated and widely accessible

Topic

Country/Region

14 January 2026

Printmaking is an ideal medium for wide and diverse engagement with art: it is replicable, cheap, and widely accessible. These features have made prints particularly attractive to political activists looking to inspire collective mobilisation. The Statewatch Library & Archive contains a number of examples of the medium, from a wide variety of movements.

Support our work: become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Print in politics

Printmaking played an important role in many of the 20th century’s most influential political movements:

- in Western Europe, expressionist printmakers stood in opposition to the First World War;

- in China, the New Woodcut Movement denounced the Japanese invasion and the Guomindang regime;

- in Latin America, members of the Asociación de Grabadores de Cuba (Cuban Printers’ Association) promoted the revolutionary cause; and

- Mexico’s Taller de Gráfica Popular (Popular Graphics Studio) confronted fascism.

Making prints

Publications held in the Statewatch Library & Archive contain a variety examples of print art, with woodcut and linocut prints featured below.

A woodcut print is produced by carving a block of wood. Ink is then applied onto the surface with a roller, leaving the carved sections untouched by ink. A sheet of paper is then pressed onto the inked surface. The same method is applied to a block made of linoleum to produce linocut prints.

These techniques are accessible to anyone with a carving tool, a woodblock, paper, and ink. Primary school children will often be encouraged to do something similar, using potatoes as the surface to be carved.

Unlike other printing methods such as etching and lithography, woodcuts and linocuts do not require presses, chemicals, stone or metal plates. This concealable simplicity ensured the survival of the clandestine Chinese New Woodcut Movement.

Art and activism

The use of prints for political purposes does not undermine their artistic qualities. Indeed, those qualities may have contributed to their activist role.

Slogans and manifestos can guide and convince, but prints (and other art forms) can stir compassion, and represent the torments and ideals of a group.

Woodcuts have the potential to convey strong emotions, particularly through vivid subjects, clear lines, and striking contrasts.

The harrowing woodcuts produced by Käthe Kollwitz and Lu Xun are some of the most prominent examples of this effect.

Prints in the Statewatch Library & Archive

The following images, included in materials held in the Statewatch Library & Archive, were selected for their artistic and historical value.

Their representation of political events through the aesthetics of woodcuts and linocuts demonstrates the significance this medium has held for campaigning and political groups and organisations.

Clifford Harper

This illustration for the 1999 London Anarchist Bookfair is an ink drawing in the woodcut style. It is Clifford Harper’s ninth and last annual poster for the bookfair.

Much of Harper’s work reflects his commitment to anarchism. He has illustrated multiple books and is a regular contributor to The Guardian. The London Anarchist Bookfair is still held in autumn every year.

Idiot International

This print represents protests in Amsterdam during the spring and summer of 1970.

The article it accompanies (‘Amsterdam pot, pixies, & politics’ by Robin Derricourt) describes students occupying university buildings to advocate university reforms, the student union’s attempt to engage with “industrial militants”, and the diversity of protesters at Dam Square, from “American Express hippies” to Roeland Van Duijn’s Kabouters movement.

The print is the back cover of the July 1970 copy of Idiot International, the short-lived British version of a French newspaper founded by Jean-Paul Sartre and Jean-Edern Hallier. The Statewatch Library & Archive has copies of issues 6, 7 8 and 9 of the magazine.

Atelier Populaire

In May 1968, during the student occupation of the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, a group of artists known as the Atelier Populaire produced posters in support of the massive strike and protest movement of workers and students across France.

The tears in the posters, shown on the cover of an issue of Anarchy, may hint at the polarized reaction of the French public. The print associates the riot police, the Compagnies républicaines de sécurité (CRS), with the infamous Nazi paramilitary group, the Schutzstaffel (SS).

In the magazine, John Vane writes:

…there will be violence in every serious struggle, and violent resistance is better than no resistance — but we must question the current revival of interest in and approval of violent means which brings us closer to our enemies in more ways than one.

Seth Tobocman

Tobocman’s work explores activist struggles spanning from the 1980s to the present day, from opposition to the separation wall in the occupied Palestinian territories to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and, in this pamphlet, gentrification in New York.

His firsthand account of gentrification in New York City’s Lower East Side led to the creation of the book War in the Neighborhood.

Tobocman cites the woodcut printmakers Frans Masereel and Lynd Ward among his creative inspirations.

Ed dela Torre and Mariya Villariba

As the dove and the references to nature and dualism suggest, the character in the picture might be a babaylan, a “mystical wom[a]n who wielded social and spiritual power in pre-colonial Philippine society”.

Mariya Villariba was the director of Isis International, an organization promoting feminist activism. Her husband, Ed dela Torre, was an artist and a Catholic priest.

When this issue of Briefing Papers from the Churches’ Committee for Migrants in Europe was published in 1991, Ed and Mariya had spent the last decade living in political exile from the Philippines.

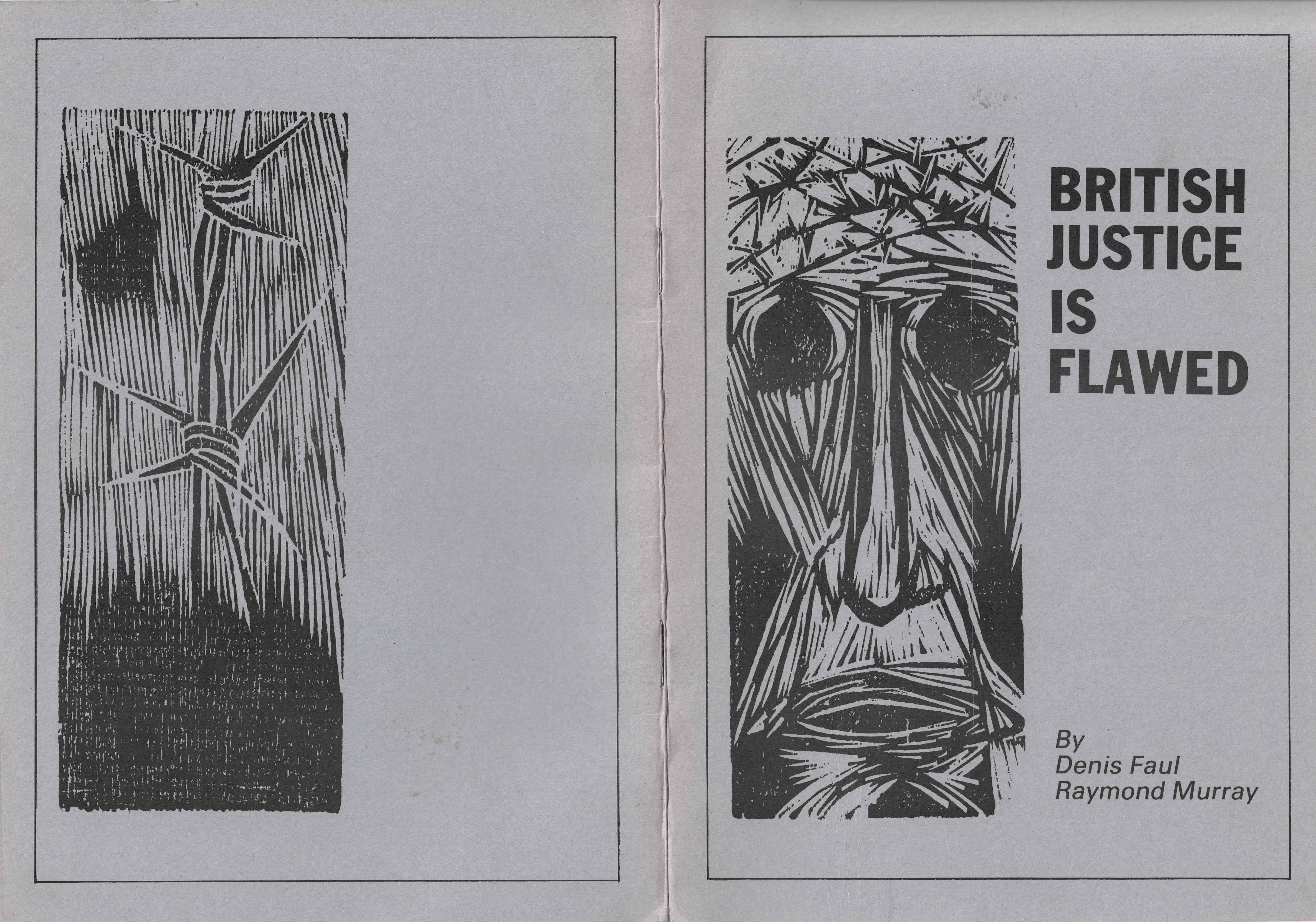

“British justice is flawed”

This 1988 pamphlet expresses concerns about the prospect of extraditions from the Republic of Ireland to the UK and denounces detention conditions for Irish people in England.

Issues included pre-charge detention (up to a week under the Prevention of Terrorism Act 1984, later increased to two weeks under the Terrorism Act 2000); bias among judges in the first appeal for the Birmingham Six case, and discriminatory treatment of Irish prisoners’ families.

Denis Faul and Raymond Murray were Catholic priests and influential advocates for the rights of Irish prisoners. The artist is unknown.

The Statewatch Library & Archive

The Statewatch Library & Archive contains a wealth of materials from social and political campaigns and movements primarily in the UK (with the bulk of the material focused on the 1970s and 1980s), but also from other countries in Europe and beyond.

Visits to the Library & Archive are welcome but should be arranged in advance by phone (+44 7836 296 043) or email (library [at] statewatch.org)

It contains a range of unique materials that are not available at other libraries and archives (whether conventional or otherwise), including:

- nearly 800 books, including classic historical sources;

- over 2,500 items of ‘grey literature’ (pamphlets, zines, reports and more) on political and social struggles and movements;

- hundreds of official government, state and parliamentary reports;

- EU documents: over 1,000 hard copy documents and reports from the pre-web era that are not currently in the Justice and Home Affairs Archive;

- ABC Case Archive donated by Crispin Aubrey’s family, 70+ files;

- The special collection: currently has 45+ unique subject files, some of which ‘dropped off the back of a lorry’, e.g. the BBC TV News discussion files 1977-79;

- Journals: complete and partial runs of 60+ publications; and

- 365+ political badges.

The catalogue can be consulted online.

Our work is only possible with your support.

Become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Further reading

UK: Electronic tagging: the normalisation of a “fascist or totalitarian” technology

Electronic tagging has long been a controversial means of monitoring and restricting the movement of people outside of prisons. The British government is expanding the use of electronic tagging against people with criminal convictions, asylum seekers and migrants. A report from 1989, held in the Statewatch Library & Archive, shows remarkably fierce opposition to the practice from what might seem an unlikely source: the Prison Officers’ Association.

UK: Police monitoring, suspect communities, racism and policing reform – learning from the past to inform the present

Statewatch Library & Archive goes online after event in Bristol

Spotted an error? If you've spotted a problem with this page, just click once to let us know.