EU deportation proposals: the member states sink to new depths

Topic

Country/Region

03 October 2025

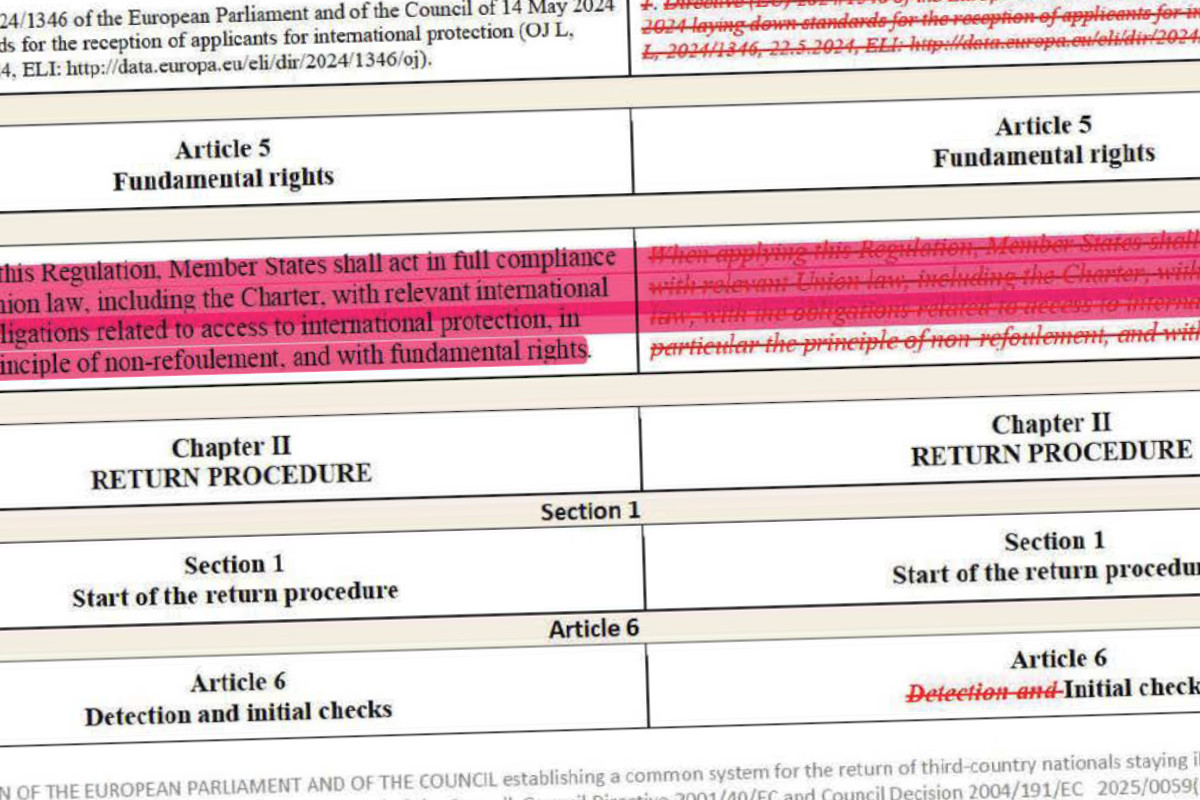

A new compromise text for the upcoming deportation Regulation was recently circulated by the Danish presidency of the Council of the EU. Alongside two other legal proposals currently under discussion, the deportation Regulation forms the legal basis for the EU’s plan to increase deportations, in particular by forging new ‘Euro-Rwanda’ deportation schemes. The latest text makes even more cuts to safeguards and protections.

Support our work: become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Beyond rock bottom

In 2012, EU law professor Steve Peers concluded that the member states had hit “rock bottom” in proposals on reception conditions for asylum-seekers.

The most recent Council presidency version of the proposed deportation Regulation (pdf) shows that, in fact, they have found new depths to sink to when it comes to the (mis)treatment of foreign nationals.

The summary below demonstrates the degree to which the Council may be willing to reduce, limit or eliminate safeguards for people subject to deportation orders. Changes in the latest proposed version of the text, produced by the Danish presidency:

- remove administrative barriers to deportation at multiple stages of the process;

- dilute protections, human rights safeguards and legal remedies;

- allow people to be deported with far less information on their rights and the process;

- place asylum seekers at greater risk of detention, and allows for detention in prisons with no access to the open air, if considered necessary;

- enact measures designed to keep people out of Europe for good;

- dilute protections for children and their families, including by removing references to the best interests of the child, a principle of international law; and

- transfer procedural duties and obligations from member states onto deportees.

The presidency’s compromise text reflects a desire to remove as many human rights barriers and administrative hurdles to deportation as possible.

A lot of the changes can be seen simply as ‘tuning up’ the language of the text to remove ambiguities, but there are also significant differences in the compromise document from the previous version of the proposal.

Administrative barriers

The compromise text would allow member states to bypass many existing procedures in order to effect deportations as quickly as possible.

Examples of this are:

- Under Article 8 (Exceptions from the obligation to issue a return decision), language has been removed protecting people from return decisions if they have a current visa application/renewal pending.

- Under Article 25 (Legal assistance and representation) language is diluted on the requirements to provide free, automatic representation, as well as the various administrative tasks associated with that representation. Legal assistance from people with potential conflicts of interest is no longer explicitly proscribed.

- Under Article 17 (…agreements or arrangements) member states would no longer be obliged to inform the EU of an agreement prior to its conclusion.

- Member state powers to remove a person on the grounds of them being a ‘security risk’ have been expanded, and subsequent entry bans could be made indefinite “where justified and proportionate” to security risks.

- Various sections of the proposal appear to take procedural responsibility away from member states and place it on the person to be deported, particularly in ways that incentivise compliance. This includes reviews on entry bans becoming the individual’s responsibility to request and justify, and only where they have previously “complied” with a deportation. Similarly, the language of the text appears to place on the individual the burden of substantiating a claim of refoulement

- States would be freer to limit where individuals can live and travel to on their territory, in order to “ensure an effective return”. They are also given wider search and seizure powers, without consent and including the collection of biometric data “using means of coercion”.

- Member states are also afforded flexibility in mutual recognition of deportation orders and will be supported in returns with EU funds.

- Time limits for ‘voluntary’ return are notably missing, apparently leaving it to member states’ discretion.

- References to measures ensuring readmission after a deportation have been removed. Member states are not obliged to make use of EU reintegration programmes.

Clear, accessible communication

Member state obligations to ensure people subject to deportation are fully informed about their rights and the process are significantly diluted.

For instance:

- Under Article 7 (Return decision), member states may, under the new wording, “use generalised information sheets or translations, including machine-generated translations” when communicating the details of the return decision and available legal remedies.

- Under Article 24 (Right to information):

- a person would no longer be explicitly mandated to receive information about the duration and steps of a removal procedure, nor “information on the available legal remedies and time limits”;

- information would no longer have to be provided in “simple and accessible language”; and

- authorities would not be obliged to confirm receipt of communication.

- Under Article 46 (Support for return and reintegration), language is modified to make the provision of “information about return and integration” voluntary.

- Individuals may be notified orally of a detention decision.

Elsewhere, more subtle changes can be found, such as information being delivered in a language someone “can communicate in” rather than “speaks” (this is also found in the language on age-appropriate communication with children). Numerous examples of dilutions, similar to those above, can be found throughout the proposal.

Expanded detention powers, degraded conditions

Member states would be equipped with much greater powers to place people in detention or subject them to “alternatives to detention” (which may include, for example, GPS tagging), and requirements to ensure detainees’ safety and wellbeing have been reduced.

- Article 29 (Grounds for detention) expands the list of justifications for detaining a person. Such reasons now include non-cooperation in obtaining travel documents, as well as “other relevant grounds” without those grounds having to be laid down in national law.

- Where people cannot be returned, they may still be detained or subject to other consequences in order to ensure compliance.

- Article 30 (Risk of absconding) now includes “explicit expression of intent of non-compliance” with a return decision, or “actions clearly demonstrating” the same, as grounds to detain. “Violent” resistance to a removal has been changed to “physical”. Member states may also work from their own criteria.

- Under Article 34 (Detention conditions):

- safeguards that prevented detained people being housed in prisons or, failing that, to be separated from the regular prison population, are now optional;

- detainees may be deprived of access to open-air space if considered “necessary” for facility operations;

- attention should be paid to the “needs of vulnerable persons”, but “accommodation” to those needs would no longer be required;

- member states are afforded considerable freedom in restricting visitation rights of family and legal representatives.

- Under Article 31 (Alternatives to detention), measures no longer would have to be “proportionate” to absconding risks, and member states would no longer have to take into account a person’s vulnerabilities in applying ATD measures. Member states may also apply their own ATD conditions under national law.

- Article 22 (Consequences in case of non-compliance with the obligation to cooperate leaves member states free to impose their own consequences or “dissuasive measures” for non-compliance.

- Article 32 (detention period) would see member states given greater latitude to extend detention if deemed necessary. Some of the language suggests that detention may be extended for the sole reason of keeping a person physically to hand for a deportation where a “reasonable prospect” of that removal has emerged (if new information has come to light or cooperation with a third country has improved, for instance). Someone complying with a voluntary return may nonetheless be detained throughout “to ensure effective return”.

- Regarding the detention of unaccompanied minors (Article 35), gender-based protections have been removed, as have explicit requirements to provide “appropriate hygiene, food (and) health services”.

Diluted protections, remedy, safeguards

- Under Article 27 (Appeal before a competent judicial authority), a requirement for national law to ensure “an adequate and complete examination” of appeals against deportation decisions has been deleted.

- Article 33 (Review of detention orders) appears to remove language ensuring member states provide “all relevant facts, evidence and observations” to a detention order review.

- A section in Article 26 (The right to an effective remedy) mandating that the “principle of non-refoulement is verified by the competent judicial authority” has been deleted.

- Under Article 25 (Legal assistance and representation) language ensuring automatic, free legal assistance and representation for unaccompanied children has been diluted. A previous exception for monetary and time limits on legal assistance to children has been deleted.

- Regarding the ‘suspensive effect’ of a deportation order, language in Article 28 (Suspensive effect) has been changed so that it must be requested, rather than apply automatically. Another section ensuring decisions on suspension be made within 48 hours has been deleted.

- Personal data protections have been significantly watered down. Under Article 38 (Information sharing between member states), rules on how data is transferred between member states have been loosened, and a requirement that requested data be “adequate, relevant, accurate (and) limited to what is necessary for the intended purpose” has been deleted. Limitations on the various categories of data that can be shared – identity and personal information, legal status, pending residence applications – have been loosened. “Information on compliance” has been added.

- Rules on data transfer to third countries or third parties have been similarly loosened.

- Frontex would no longer have to satisfy itself that “the transfer of data does not risk (refoulement)” prior to the data being sent.

- Entry bans could now be extended to twenty years, if “duly substantiated”.

Protections for families and children weakened or removed

As has been noted in delegation discussion documents, member states consider it acceptable to roll back protections for unaccompanied children. The compromise proposal reflects this, and also weakens protections for families with children.

- Under Article 19 (Age assessment of minors), age assessments requirements have been significantly diluted. Where previously a “multi-disciplinary assessment, including a psychosocial assessment… by qualified professionals” was required, the new test says only that age assessments have to be in line with national law. Member states may also rely on age assessments made previously, including in other member states.

- Under Article 20 (Return of unaccompanied minors) the following passage has been deleted: “Before deciding to issue a return decision in respect of an unaccompanied minor, assistance by appropriate bodies other than the authorities enforcing return shall be provided in accordance with the best interests of the child.”

- Language over the kind of representation a child must be provided with has been diluted. Requirements for clear and accessible communication have been similarly loosened.

- Under Article 17 (Return to a third country…) families with minors are no longer protected from deportation.

Documentation

Our work is only possible with your support.

Become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Spotted an error? If you've spotted a problem with this page, just click once to let us know.