When informal means illegal: Italian interior ministry guilty of pushbacks to Slovenia

Topic

Country/Region

26 January 2021

A court in Rome has ruled that “informal readmissions” from Italy to Slovenia are unlawful, in a case concerning a Pakistani asylum seeker who was subjected to a series of violent pushbacks stretching from Italy to Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Support our work: become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Informal readmissions unlawful

A ruling by Rome tribunal (personal rights and immigration section) on 18 January 2021 declared the practice of "informal readmissions" from Italy to Slovenia that have intensified since the spring of 2020 to be unlawful, Altreconomia reports.

The ruling concerned a case brought by lawyers Caterina Bove and Anna Brambilla on behalf of a Pakistani asylum seeker who was sent back from Italy after reaching Trieste, and who ended up living in destitution in Sarajevo in a case involving serial pushbacks.

The legal complaint cited violence suffered at the hands of Slovenian authorities and torture and inhuman treatment meted out by the authorities in Croatia. The court was asked to recognise the plaintiff’s right to apply for asylum in Italy and for the competent administrations to allow him access to asylum procedures, in accordance with Article 10.3 of the Italian Constitution.

In her ruling, judge Silvia Albano specified that informal readmissions based on a 1996 bilateral agreement between Italy and Slovenia clearly contravened the Constitution, the European Convention on Human Rights and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, not just for asylum seekers, but for anyone who reaches Italy’s north-eastern border.

The judgement states that such readmissions knowingly placed people at the risk of inhuman and degrading treatment along the Balkan route and torture in Croatia, and orders the authorities to allow "the plaintiff’s immediate entry into Italian territory as an asylum seeker" (emphasis in original) and file his application for international protection.

In an interview with Altreconomia, Caterina Bove welcomed the ruling and noted its systemic importance concerning practices that have become routine at Italy’s north-eastern border, adding that it does not just apply to asylum seekers and that Italy has an obligation to register any asylum applications that are made.

Inhumane treatment

The plaintiff had fled his home country, where he was persecuted for his sexual orientation and for stating that he was an atheist. Having eventually arrived in Trieste in July 2020, after having tried to cross the border ten times, he was subjected to a series of refoulements over a 48-hour period.

While the applicant was seeking assistance from volunteers in Trieste, two plainclothes officers asked about his migration route and then took him to a site run by the border authorities. Despite his repeated requests to apply for asylum, he was not taken to the competent authorities. Instead, a file that included his photograph was compiled before he was held with a group of other people, informally and without any judicial order.

He was made to sign some documents written in Italian and had his mobile phone confiscated. Then, he was handcuffed, loaded onto a van, left in a hilly area near the Slovenian border and told to run with his fellow migrants. They stopped when they heard gunshots and the Slovenian police detained them.

They spent a night in Slovenia without access to hygienic services, food or water, and officers laughed or ignored them when they asked to use a toilet. They were subsequently expelled to Croatia, whereby the plaintiff and his fellow migrants were "dumped" by the police at the border, where Croatian police officers wearing dark blue T-shirts, black trousers and boots were waiting for them.

Still in Slovenia, they were made to lie down, cuffed, beaten with kicks and truncheon blows at a border post before the handover, and they were beaten again, kicked in the back and struck with truncheons wrapped in barbed wire by the Croatian police.

They were loaded into a van and taken to a place where they said they wanted to apply for asylum, but instead were taken to the Bosnian border where a countdown was followed by a further attack, using blows, pepper spray and a German shepherd dog was spurred to intimidate, bite and run after them.

Once in Bosnia, there was no place for the plaintiff in the overcrowded Lipa camp and he was left in the countryside, from where he reached Sarajevo and found shelter in an abandoned building, semi-destroyed in the war of the 1990s.

The ruling notes an abundance of supporting documentation provided in the case, including photographs, press accounts, NGO reports (Border Violence Monitoring Network closely followed and reported the case), national, EU and international legal sources and answers to parliamentary questions concerning informal pushbacks. The treatment the plaintiff was subjected to was deemed to have been proven, and the Italian interior ministry did not challenge the case brought against it.

Parliamentary confession

In her ruling, Albano analysed a reply from the Italian interior minister, Luciana Lamorgese, to a parliamentary question on the implementation of the 1996 bilateral Italian-Slovenian readmission agreement, and determined that it confirms “unlawful” acts.

The minister had stated:

"… informal readmission procedures to Slovenia are applied to migrants identified near the Italian-Slovenian borderline, when people have arrived from Slovenia, even when the will to apply for asylum has been expressed…" (emphasis in original, underlining by the judge)

Exceptions to this rule cover people who have previously applied for asylum in an EU state (who are registered in the EURODAC database) and to people who have already been granted refugee status.

Lamorgese’s answer also noted that the expedited procedures permitted by the readmission agreement do not foresee any written records being made of the incident. If the preconditions for readmission apply and the Slovenian authorities agree:

"the invitation to the Questura [police chief’s office] to formalise the request for international protection does not take place".

Such practices are unlawful, ruled Albano. The bilateral agreement was never ratified by the Italian Parliament and, therefore, it cannot suspend or derogate the application of Italian laws, EU norms or those deriving from international law.

Illegality in detail

Regarding the practice of informal returns to Slovenia, The ruling sets out further details:

- there is no formal measure issued despite its effects for legal subjects, making appeals or remedies impossible;

- the measure restricts personal freedom and must be validated by a judicial authority;

- the right to legal remedy and to individual assessment of situations (Article 19 Charter of Fundamental Rights, CFR) forbids collective expulsions and also contributes to upholding the absolute ban on inhuman and degrading treatment (Article 4 CFR, Article 3 European Convention on Human Rights, ECHR) and the non-refoulement principle;

- Article 3 ECHR does not allow any derogation or exceptions;

- drawing on abundant jurisprudence by the ECHR and ECJ, 2013 amendments to the EU Dublin Regulation exclude transfers to member states when there is reason to believe that systemic shortcomings in asylum procedures and reception conditions for asylum seekers entail a risk of inhuman and degrading treatment;

- the Italian Court of Cassation upheld the above principle in 2018, requiring an assessment of conditions where people will be transferred to;

- Italian immigration legislation (law 286/98) forbids transfers to countries from which a foreigner may be transferred to another state where they may endure “persecution, torture or inhuman and degrading treatment”;

- Italy should not have enacted informal returns to Slovenia with no guarantees about people’s treatment or that their rights would be upheld;

- the interior ministry should have known (on the basis of plentiful available documentation from international bodies and NGOs) that returns to Slovenia were likely to entail a pushback to Croatia and then Bosnia;

- the ministry should have also been aware of the likelihood that migrants may suffer inhuman and degrading treatment, or veritable torture, at the hands of the Croatian police;

Thus, Albano ruled, Italy must be deemed guilty of violating Articles 3 and 13 of the ECHR, Article 4 of the 4th protocol to the ECHR, as well as Articles 4 and 19 of the CFR, a finding strengthened through reference to the Sharifi et al vs. Italy case.

Regarding the 1996 Italian-Slovenian readmission agreement, the judgment confirms that it is subordinate to EU law, in particular the CFR, and even where the EU Returns Directive (in Article 6(3)) allows readmissions between neighbouring states in presence of bilateral agreement, the Italian state is also bound by Article 13 of its Constitution, on personal freedom. Prevalent supranational norms also oblige the authorities to check the situation to which a person will be returned.

The right to seek asylum

The court also emphasised that:

“informal readmission can never be applied to an ASYLUM SEEKER, without even registering their request, with a praxis that violates the national and international normative frameworks in this field”

The Italian state admits that informal returns take place without distinction between asylum seekers and others, resulting in asylum seekers not having their status recognised in Italy or Slovenia.

Furthermore, the informal return prejudiced the applicant’s right of access to international protection procedures. Even if it is made orally (which the law allows), a request for asylum excludes the possibility of someone being irregularly present in a territory, which means that the bilateral readmission agreement with Slovenia is not applicable, even on its own terms.

The EU Asylum Procedures Directive (2013/31) binds member states to grant applicants effective access to procedures to examine and recognise international protection needs and they should provide a temporary residence permit to request asylum. Article 10.3 of the Italian Constitution rules out the applicability of irregular entry once a person has requested asylum, even if they have entered irregularly.

The Dublin III Regulation requires that identification of the state responsible for examining an asylum application must commence when a request is made in a member state, but transfers to the responsible state are not automatic – they cannot take place if an individual’s rights will be violated or they are at risk of inhuman and degrading treatment, and there must be scope for appealing against a transfer. Further, the ECJ has repeatedly stated that a MS’s compliance with human rights cannot be simply assumed on the basis of EU membership and that certain limits apply to mutual trust.

Hundreds of cases

The pitiful circumstances of the plaintiff’s journey are not unique. At a press conference on 8 September 2020, Lamorgese reported that 852 people had been readmitted in Slovenia.

The nationalities of the people most affected by this practice indicates their likely need to enjoy international protection rather than being repatriated – the largest group were Afghans, followed by Pakistanis, Iraqis, Iranians and Syrians.

Shortcomings in the Slovenian system for managing asylum seekers and the likelihood of chain returns to Croatia (where they were liable to be beaten) and Bosnia were notorious, as has been well-documented by NGOs, the press and international organisations, including the UNHCR.

Since December 2019, the Danish Refugee Council has recorded 14,090 pushbacks from Croatia to Bosnia, with a recent increase accompanied by greater violence in the execution of pushbacks involving violence, torture and the confiscation and destruction of personal belongings.

Both the UNHCR and the UN Special Rapporteur for the human rights of migrants, Felipe Gonzales Morales, have expressed deep concern over the Croatian police’s violence against migrants and asylum seekers. The tough Bosnian winter and the ongoing pandemic have further intensified concern for people’s survival and over the treatment of people classified as vulnerable, including unaccompanied minors.

The Italian organisation ASGI (Associazione Studi Giuridici sull'Immigrazione), of which the lawyers Bove and Brambilla are both members, highlighted that the readmission procedure:

"is undertaken in obvious violation of international, European and internal norms that regulate access to asylum procedures, it is executed without the interested people receiving any formal measure and without their personal situations being examined, hence clearly prejudicing the right to defence and the right to submit an effective appeal." (emphasis in original)

The Serbian Constitutional Court has also recently ruled against irregular pushbacks from Serbia to Bulgaria.

Comment: Yasha Maccanico, Researcher for Statewatch

“The ruling applies to a multitude of cases involving unlawful practices that have become routine, like those at the Italian north-eastern border, on the basis of pseudo-legal bilateral political agreements that undermine superordinate legal instruments and norms.

The practice of informal pushbacks by Italy, Slovenia and Croatia fits into an EU strategy to lower the number of recorded irregular border crossings and asylum applications, within which Frontex has turned its gaze to the Balkan route in recent years and when there has been an increase in human rights violations and outright violence.

It is a welcome development for this legal challenge to have been upheld and it offers a legal remedy for an asylum-seeker who had entered Italy but was not allowed to submit an application.

ASGI, BVMN and several actors deserve praise for this outcome alongside lawyers Bove and Brambilla.

The problem of informal agreements used to undermine prevalent national, EU and international legal instruments may be argued to also apply to bilateral deals struck with Libya by Italy (2017) and Malta (2020) and to the EU-Turkey deal (2016), all of which undermine access to asylum procedures and the absolute prohibition of inhuman and degrading treatment, if not torture.”

Sources

- Ordinanza, Tribunale Ordinario di Roma, Sezione Diritti della Persona e Immigrazione, N. R.G. 56420/2020, 18 January 2021 (link to pdf)

- Duccio Facchini, I respingimenti italiani in Slovenia sono illegittimi. Condannato il ministero dell’Interno, Altreconomia, 21 January 2021

- ASGI, Riconosciuto il diritto a fare ingresso in Italia a chi ha subito una riammissione a catena verso la Bosnia, 21 January 2021

- Nemanja Rujevic, Serbien schiebt Asylbewerber ab - in die EU, DW, 22 January 2021

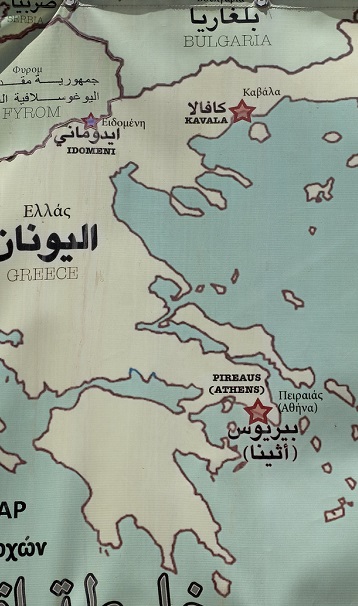

Image: Andrea Diener, published under a CC BY-NC 2.0 licence.

Our work is only possible with your support.

Become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Spotted an error? If you've spotted a problem with this page, just click once to let us know.