3. Security AI in EU agencies

EU agencies are already developing and using various types of AI technology. This section looks in particular at projects and activities launched by eu-LISA and Europol, as well as Frontex, Eurojust and the EU Asylum Agency. There are a wide variety of AI technologies - from facial recognition to machine learning and 'predictive' technologies - that have been examined or are actively deployed.

Support our work: become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

In this section

3.1 eu-LISA

3.1.1 Algorithmic profiling of travellers

3.1.2 AI in the shared Biometric Matching System

3.1.3 Digitalising the visa application process: visa chatbot

3.2 Europol

3.2.1 From challenge to opportunity

3.2.2 Machine learning

3.2.3 Facial recognition

3.2.4 Data protection and European policing

3.3 Frontex

3.3.1 AI in the maritime domain

3.4 EU Asylum Agency

3.4.1 Automated dialect recognition for asylum applicants

3.5 Eurojust

3.5.1 Joint Investigation Teams platform

EU agencies are already developing and using various types of AI technology. This includes:

- systems for the algorithmic profiling of travellers (eu-LISA);

- machine learning for the analysis of massive quantities of data (Europol); and

- systems for automatic dialect recognition, to be used to determine the nationality of refugees (EUAA).

The implementation of the Act will require new bureaucratic processes and procedures to justify and manage the use of these systems. However, it is unlikely to fundamentally change how they operate. Whatever impact the Act has will not be felt for some time. A carve-out for the EU’s large-scale IT systems (section 2.3.1) means the rules may not apply to them until 2030.

Even where the Act does apply, it remains to be seen whether EU agencies’ systems for internal accountability, combined with the external supervision of the European Data Protection Supervisor, will ensure the law is applied as intended.

3.1 eu-LISA

The EU Agency for the Operational Management of Large-Scale IT Systems in the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice is usually referred to as eu-LISA. It has its headquarters in Tallinn, Estonia, with technical infrastructure hosted in Austria and France. It “manages large-scale IT systems that support the implementation of asylum, border management and migration policies in the EU.” These are:

- the European Travel Information and Authorisation System (ETIAS)

- the Schengen Information System (SIS);

- the Visa Information System (VIS).

It is also developing a number of other systems that are due to be introduced:

- the Central Repository for Reporting and Statistics (CRRS);

- the Common Identity Repository (CIR);

- the Entry/Exit System (EES);

- Eurodac;

- the European Criminal Records Information System on Third-Country Nationals (ECRIS-TCN);

- the European Search Portal (ESP); and

- the shared Biometric Matching System (sBMS).

The purposes of these systems include the sharing of information between police, border and judicial authorities (SIS); the storage and processing of information on visa applicants (VIS); the storage of biometric and biographic “identity data” on non-EU citizens (CIR); and the registration of border crossings by all non-EU citizens (EES).[1]

The agency is incorporating various forms of AI into the systems it manages. In 2021, these initiatives – and others – were incorporated into a “roadmap” on AI initiatives. One initiative was the establishment of a Centre of Excellence for AI for justice and home affairs policies, examined in section 4.1.1 as a form of institutional infrastructure. With regard to the use of AI technologies for the EU’s large-scale IT systems, three initiatives from the roadmap are examined below:

- the algorithmic profiling of travellers;

- the use of AI in the shared Biometric Matching System; and

- the development of a “chatbot” to support the visa application process.

3.1.1 Algorithmic profiling of travellers

Of the EU’s current AI projects, the one likely to have the most widespread impact concerns the use of automated risk profiling against travellers. In the years to come, anyone travelling to the Schengen area who requires a short-stay visa or a travel authorisation will be subjected to an array of automated screening and profiling techniques. As remarked in a previous Statewatch report, “people visiting the EU from all over the world are being placed under a veil of suspicion in the name of enhancing security.”[2]

Visas and travel authorisations

Citizens of more than 100 countries must acquire a visa to enter the Schengen area legally. Those countries are largely poor (or, at least, poorer than EU states), with majority non-white populations.[3] Those who wish to travel to the Schengen area must go through a lengthy, invasive and often expensive application process.

The EU is also in the process of creating a separate travel authorisation process, for citizens of countries who do not need a visa to enter the Schengen area.[4] While the application process is neither as expensive, intrusive or inconvenient as that for a visa, it amounts to the same thing: you require government permission to travel, and must pay and hand over information for the privilege.

Both categories of traveller will be subject to AI decision-making techniques, once the EU’s “interoperability” architecture has been set up. The interoperability architecture will interconnect six large-scale policing, migration and criminal justice databases that hold biometric and biographic data on tens of millions of people, and create three new large-scale databases.

The aim is to make it easier for officials to access data on non-EU citizens, and to make it possible to use large amounts of personal data in new ways. For example, large amounts of data must be mined to develop the various “risk profiles” and “screening rules” that will be used to single out supposedly risky travellers.

All Schengen visa applicants have their personal data a stored in a database called the Visa Information System (VIS). For individuals who have to apply for a travel authorisation system, the equivalent is the European Travel Information and Authorisation System (ETIAS). Through the interoperability architecture, visa and travel authorisation applications will be cross-checked against other connected European and international databases. Statistical data will also be used to determine whether an individual belongs to a group considered to pose a potential risk.

Statistical power

As part of the interoperability project, the EU is constructing a database called the Central Repository for Reporting and Statistics (CRRS). This will extract data from the VIS, the ETIAS and four other large-scale databases, to allow the generation of data and statistics on all manner of events: border crossings; refusals of entry; non-EU citizens overstaying their allotted time in the Schengen area; the number of asylum applicants in the EU; and much more.[5]

When it was first proposed by the group of officials that set out the interoperability plans, it was referred to as a “data warehouse.” The aim, in their words, was to:

…help Member States to make better use of the systems, including by taking informed decisions on EU policies in the area of migration and security. It would also provide valuable statistics for relevant agencies in these areas, to perform analytical reviews.”[6]

The “valuable statistics” include those that will be used by the ETIAS Central Unit, hosted at Frontex, to generate “specific risk indicators.” Those indicators will be used to flag travelling individuals as risky or not. They include age range, sex and nationality; country and city of residence; and the type of employment the visa or travel authorisation applicant holds.

|

Basis for the specific risk indicators |

|

|

ETIAS |

VIS |

|

age range, sex, nationality |

age range, sex, nationality |

|

country and city of residence |

country and city of residence |

|

current occupation (job group) |

current occupation (job group) |

|

the Member States of destination |

|

|

|

the Member State of first entry |

|

|

purpose of travel |

|

level of education (primary, secondary, higher or none) |

|

Building an automated profiling system

Work has been ongoing for some time to develop the technology needed to implement this plan. One document that provides further insight was finalised in November 2022. It was produced under a contract with a consortium of companies (Unisys Belgium, Unisys Luxembourg and Wavestone) for Frontex and eu-LISA, as part of a larger contract for constructing the interoperability architecture.[7]

The report is clear that it is “a research document and the outcome does not indicate that the AI Solutions will be utilized in the manner suggested and described in the Study.” Nevertheless, it provides important insight into ideas that have been developed on this topic.

The study outlines a number of requirements for the CRRS. Firstly, it should include “automated mechanisms to predict and discover potential risks.” It should also be expansive, in the sense that the techniques developed should be used in realms other than visa and travel authorisation applications. The report says that the system’s ability “to learn based on data inputs and/or outputs” should “extend beyond the specific objectives of this project.”

The AI techniques deployed in the CRRS should “allow to analyse and draw inferences from data.” At the same time, the CRRS should be only “one of the sources to be utilised by AI technology to analyse current and past information through machine learning capabilities.” The report does not specify what other sources may be used, though this would appear to go beyond the scope of the current legislation.[8]

Finally, the technology used should “enable to identify patterns within the data stored in the CRRS,” but should “not be used to predict or forecast the future.” However, despite saying this, the report includes a diagram for a “predictive analytics” function, and says that it should be possible “to generate new predictions and produce the corresponding results/outcomes.” Indeed, a component of the system called “Produce Predictions” is proposed, which would indicate that there is at least an interest in predictive technologies.

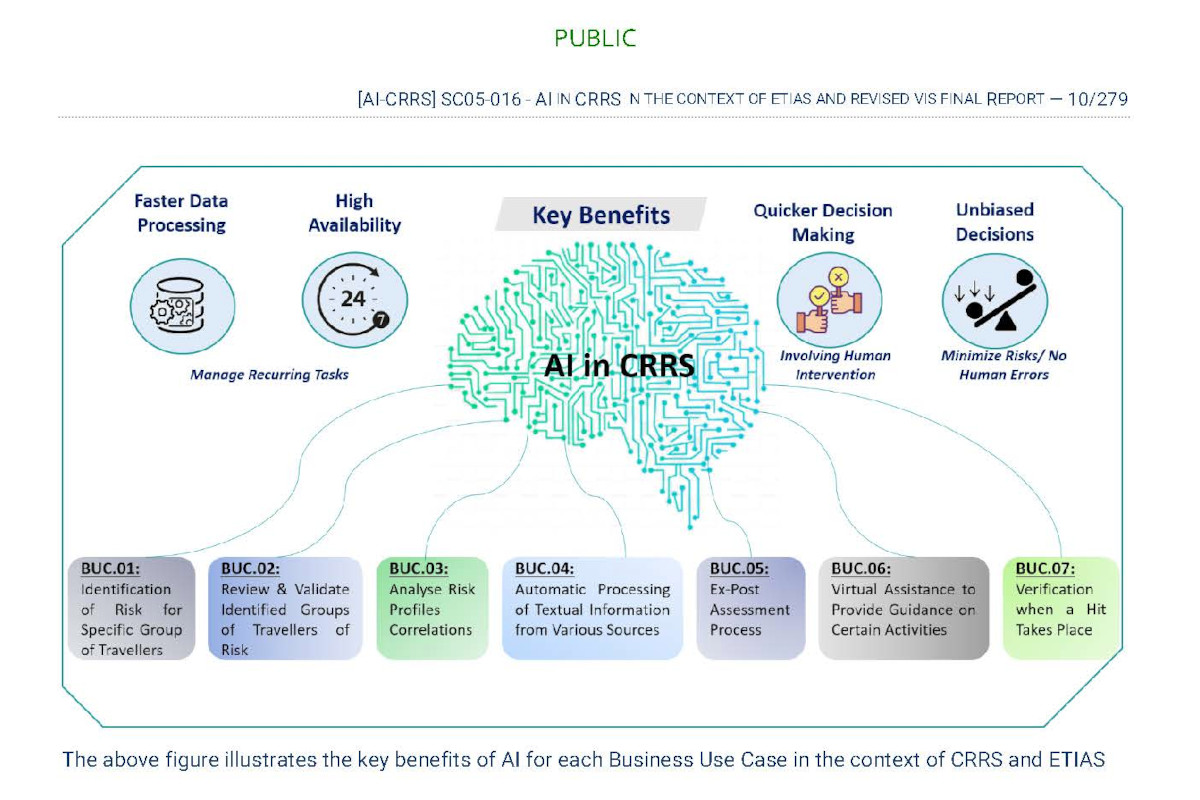

The study also examined seven possible “Business Use Cases” (BUCs) for the application of AI on visa and travel authorisation applicants.

- Identification of risk for specific group of travellers

Here, “the proposed Al technology will identify patterns or a set of common characteristics from the analysis of historical data available in the CRRS.” It would be used to identify “security, illegal immigration or high epidemic risk for a specific group of travellers,” referred to as “clusters.” These could be based on “similar age/education/occupation, etc. or any combination of the input attributes.”[9]

- Review and validate identified groups of travellers of risk

This would involve “an Al Solution that seeks for deviations from the already identified groups of travellers of risk for ETIAS.” The use case is described as “a characteristic scenario of Machine Learning (ML)-based Anomaly Detection.” A series of indicators “commonly agreed with eu-LISA’s stakeholders” would be developed to illustrate “the normal behaviour of the risk profiles.” Any individual deviating from this “‘proper/normal’ behaviour will be marked as ‘suspicious’.”[10]

- Analyse risk profile correlations

This technique would “identify and highlight correlations amongst the risk profiles from its historical data… allowing a more precise definition.” The aim would be “to comprehend the patterns between risk profiles, and further understand any underlying behaviours behind them or improve the classification process to lead to more tangible, robust and reliable results.” Algorithms for pattern recognition would be deployed “to identify any hidden trends and regularities.” The “recognition of trends” could be done by officials, or by using “state-of-the-art Machine Learning techniques.”[11]

- Automatic processing of textual information from various sources

AI technology would be deployed in this scenario to “identify text patterns or a set of common textual characteristics” in the relevant CRRS data. This would be analysed to identify clusters “that meets the criteria for the validation of a proposed risk profile.”[12] The “key concept,” according to the report, is to use CRRS data to “produce valuable insights, such as the required keywords of interest for the ETIAS database.” This would allow travel authorisation applications to be checked for those keywords in order to detect potentially risky individuals.[13]

- Ex-post assessment process

The risk indicators are supposed to be reviewed regularly by Frontex and the other agencies participating in the ETIAS Central Unit. AI technology could also be deployed to “enhance” this “ex-post assessment process.” This would be done “by analysing and detecting deviations and proposing the review of the risk indicators.”[14]

- Virtual assistance to provide guidance on certain activities

This would provide travel authorisation and visa applicants with an automated chatbot “to be provided with answers to certain questions about ETIAS.” Such a service could also be offered to officials making use of the system in their work. The report notes that “similar methodology and design may also be extended and applied to other sub-systems as well.”[15] As noted in section 3.1.3, a separate project is seeking to develop an automated chatbot for the visa application process, which evidently has parallels here.

- Verification when a hit takes place

In this use case, machine learning-based “Anomaly/Fraud Detection” would be used “to identify all relevant patterns within the provided data that will eventually identify ‘hits’.”[16] The report gives the example of when a new ETIAS risk profile is agreed. The technology could assigned a label “based on the previously trained model, indicating whether the specific risk profile is considered a ‘hit candidate’ or ‘no-hit-candidate’.” It thus appears to be a way to use AI to further refine the profiling process.

The "Business Use Cases" examined in the report on AI in the CRRS produced for eu-LISA

3.1.2 AI in the shared Biometric Matching System

The shared Biometric Matching System (sBMS) is used to “support all biometric operations required by the systems that eu-LISA runs.” This would include, for example, matching fingerprint scans taken from individuals with samples stored in the Schengen Information System or Visa Information System; or matching facial image scans with samples stored in Eurodac or the Entry/Exit System.

According to eu-LISA’s AI roadmap, the sBMS uses “Convolutional Neural Networks” for face and fingerprint matching and to generate templates from face and fingerprint scans:

Currently, the sBMS supports two types of biometric operations, both of which use AI:

- Verification, which is a comparison of two images in order to determine if they are the same. In this context, AI is used in order to analyse the image and build the templates (a mathematical representation of the image), while the comparison itself is done without using AI.

- Identification, where the AI computes the template of a specific image, associated with a specific context. The template is then stored in the database and used for later comparisons.[17]

This includes the use of AI “to enhance the ability to extract more accurate templates, specifically in cases of low quality, thus reducing the risk of false negative and false positive matches.”[18]

As the shared Biometric Matching System is a component of the large-scale information systems operated by eu-LISA, it is excluded from the scope of the AI Act until 1 January 2031. From this point onwards, it must meet the Act’s requirements. Before then, the law ostensibly designed to ensure “human centric and trustworthy artificial intelligence”[19] will not apply to it.

3.1.3 Digitalising the visa application process: visa chatbot

In November 2023, new rules for a digital Schengen visa application process were approved by EU interior ministers.[20] This will simplify the process of applying for a short-stay Schengen visa, at least for those with access to and the ability to use an online system. However, the new rules make no changes to the way in which applications are assessed or the substantive requirements for acquiring a visa.

The rules establish an EU Visa Application Platform (EU VAP), through which visa applicants will be able to enter all the information necessary to apply for a visa, with the exception of fingerprints. This will digitise substantial amounts of information that were previously provided by applicants on paper forms.

Despite this, the new rules do not introduce requirements to store this data in the Visa Information System, the EU’s large-scale centralised database on short-stay Schengen visa and residence permit applications. The newly digitised data will be stored by the state with which the visa application is filed. Given the likely perceived utility of that data for profiling and “screening” visa applicants, it may be that the rules are changed further in the future, to facilitate centralised collection of the data.

One of the novelties that will be introduced with the new digital platform is a chatbot. This is defined as “software that simulates human conversation through interaction by text or voice.”[21] The visa chatbot is supposed to provide answers “on the visa application procedure, the rights and obligations of applicants and visa holders, the entry conditions for third-country nationals, contact details, and data protection rules.”[22]

The law on digitalising the visa process does not state that the chatbot is a form of AI. Nevertheless, under the AI Act, people must be made aware when they are interacting directly with an AI system, “unless this is obvious from the point of view of a natural person who is reasonably well-informed, observant and circumspect, taking into account the circumstances and the context of use.”[23] The chatbot will also not be “the only means by which the applicant could get information on the visa procedure,” according to the law.[24]

Given that eu-LISA will manage the chatbot and that it will be related to – if not part of – the Visa Information System, it may be excluded from the scope of the AI Act until the end of the decade.[25] However, it is hard to see what benefit this would bring to either authorities or visa applicants.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the visa chatbot is that its development was intended to serve as the first project for the AI Centre of Excellence, to be based at eu-Lisa, though it has now seemingly been shelved (section 4.1.1). Both the development of the CoE and the development of the chatbot itself were farmed out to Deloitte under a 2020 contract with the European Commission. One of the reports produced under that contract states:

Approaching the CoE with a ‘dream big, start small’ vision, implies that whilst defining the end state of the CoE is the main goal, starting the implementation of the CoE from a practical project, i.e. the Visa Chatbot, is desired.[26]

By February 2022, five EU member states were involved in the chatbot project, and were working on a “proof of concept.” The aim was to put the chatbot into service from 2023 onwards.[27] However, the rules on digitalising the visa application process were not approved until November of that year, and an array of implementing decisions have to be approved by the Commission before the system can be put into use.

3.2 Europol

The EU Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation, better known as Europol, is tasked with supporting EU member states in “in preventing and combating all forms of serious international and organised crime, cybercrime and terrorism.”[28] It primarily does this by gathering and receiving large quantities of data on individuals and objects (for example, vehicles or firearms). It then analyses that data to inform and advise police operations and investigations.

In May 2021, the agency reported that it was using six types of AI technology:

- biometrics;

- “facial recognition modules”;

- “automatic identity extraction modules”;

- automatic translation software;

- tools for the automated analysis of images and videos; and

- an “AI tool for malware analysis.”[29]

An article by an unnamed Europol offers an insight into the use of some of these tools:

Europol uses AI to support high-profile investigations to extract and classify information from an increasingly large number of data sources. As such, analysts supported by the data science team use a set of AI models to classify images by automatically assigning tags to millions of pictures or to extract named entities from text, including the names of people, locations, phone numbers, or bank accounts. Other AI models allow analysts to search for images of cocaine bricks with a specific logo or detect useful information in pictures, like the number on the door of a shipment container or the name and date of birth from a picture of a badge.[30]

However, as this report demonstrates, the agency is also seeking to use other forms of AI, such as machine learning (see section 3.2.2)

As with all policing agencies, the work of Europol has high potential risks for individual rights and freedoms. Indeed, the agency has a structural role in upholding and enforcing political and social systems that cause substantial harm. For example, “facilitation of irregular immigration” is one of the EU’s top crime priorities, and Europol plays a key role in aiding investigations.[31]

The “war on smugglers” that has been ongoing for the last decade has done little to alleviate “illegal” immigration. Instead, it has pushed people to use more dangerous routes, putting their lives at risk. As a result of these enforcement efforts, thousands of people who did nothing more than drive boats have been imprisoned in Europe since 2014 on charges of facilitating illegal entry, primarily in Greece and Italy. Apparently impervious to the fact that a relentless focus on law enforcement has changed little (if anything) for the better, politicians remain wedded to it.[32]

The upshot for law enforcement agencies has been increases in their budgets and powers. In 2023, the European Commission published a proposal that would extend Europol’s powers even further, specifically in relation to the offences of human smuggling and trafficking. It was announced at the launch of the Commission’s “Global Alliance to Counter Migrant Smuggling,” and another legislative proposal, together intended to ensure a “new legal, operational and international cooperation framework against migrant smuggling.”[33] It remains to be seen whether the proposal will result in any substantial changes,[34] but its key aim is to increase the amount of data sent to Europol.

The 2023 proposal follows legal reforms that came into force in 2022. These were specifically designed to make it simpler for the policing agency to process mass quantities of data, to ease cooperation with non-EU states, and to get involved in “the development and use of artificial intelligence for analysis and operational support,”[35] in large part to simplify the processing of massive datasets.

Police and state officials frequently claim that new technologies such as AI are needed to “keep pace” with criminals. In the words of an unnamed Europol official writing in Police Chief magazine, AI can “make policing more efficient and effective.”[36] This may well be true. Whether it is ultimately a desirable outcome, however, remains open to question.

No matter how efficient and effective law enforcement agencies may be, turning complex social, political and economic issues (such as the smuggling of people across state borders) into matters to be primarily dealt with through police power sidesteps more fundamental and potentially effective responses. Attempting to increase police powers at a time of growing support for far-right political parties – already in power in a number of European states – is also giving would-be authoritarian politicians precisely what they want.

3.2.1 From challenge to opportunity

In April 2019, Catherine de Bolle, a Dutch police officer who had been appointed as head of Europol just under a year earlier, wrote to the European Data Protection Supervisor with concerns over “major compliance issues with the Europol Regulation.” She referred to those issues as the agency’s “big data challenge.”[37]

The rules that governed the agency at the time set out relatively strict rules on how it may process data on various categories of persons.[38] For example, the agency could process far more types of data on suspects than it could on victims or witnesses. However, the EDPS’ inquiry found that “it is not possible for Europol, from the outset, when receiving large data sets to ascertain that all the information contained in these large datasets comply with these limitations.”[39]

The agency had evidently been receiving vast quantities of personal data for some time. Following the terrorist attacks in Paris and Brussels in 2015, it received over 16.7 terabytes of data from national law enforcement agencies.[40] It would therefore appear that the agency was breaking the law for several years, until de Bolle was appointed and, just under a year after coming into the job, alerted the EDPS to the situation.

The EDPS’ inspection report said:

The processing of data about individuals in an EU law enforcement database can have deep consequences on those involved. Without a proper implementation of the data minimisation principle and the specific safeguards contained in the Europol Regulation, data subjects run the risk of wrongfully being linked to a criminal activity across the EU, with all of the potential damage for their personal and family life, freedom of movement and occupation that this entails.[41]

In September 2020, the EDPS formally admonished the agency and set out a number of changes the agency needed to make to comply with the law. Europol failed to meet these requirements. In response, the EDPS issued a deletion order at the beginning of 2022. The supervisory authority noted that while Europol had put in place “some measures” since September 2020, the agency:

…had not complied with the EDPS’ requests to define an appropriate data retention period to filter and to extract the personal data permitted for analysis under the Europol Regulation. This means that Europol was keeping this data for longer than necessary, contrary to the principles of data minimisation and storage limitation, enshrined in the Europol Regulation.[42]

The response to this decision came from the European Parliament and the Council of the EU. Rather than seeking to ensure compliance with the law as it stood, they changed it to legalise Europol’s practices. In June 2022, changes to the law governing the agency came into force. These allowed the agency to continue processing the personal data of individuals with no established link to criminal activity. What was once a big data challenge had become a big data opportunity.

Europol’s Management Board then landed itself in hot water with the EDPS in relation to the changes. The Management Board had to adopt decisions setting out how the agency would implement the legal changes. At the end of June 2022, it did so – but did not consult the EDPS, which it was legally required to do. After the EDPS raised the issue with Europol, the Parliament, the Council and the Commission, an agreement was reached between the EDPS and the Management Board.[43]

Despite all these twists and turns, the saga is not over yet. In September 2022, the EDPS filed a legal case against the Parliament and Council that sought to annul the relevant parts of the legislation, noting that “the co-legislators have decided to retroactively make this type of data processing legal,” contrary to the EDPS order to delete the data in question. The EDPS said that the changes to the law undermined “the independent exercise of powers by supervisory authorities,” and that the legal action sought to ensure that legislators could not “unduly ‘move the goalposts’ in the area of privacy and data protection.”[44] However, the Court of Justice of the EU found the complaint inadmissible. An appeal is pending.[45]

3.2.2 Machine learning

While the EDPS investigation into Europol’s “big data challenge” was ongoing, it also had a number of other cases to deal with. In May 2019, a month after de Bolle wrote to the EDPS about Europol’s big data challenge, the EDPS launched an inquiry on a different topic. The supervisory authority sought information on “the use of operational data for data science purposes,” namely “the training, testing and validation of machine learning models.”

According to the multinational computing corporation IBM:

Machine learning (ML) is a branch of artificial intelligence (AI) focused on enabling computers and machines to imitate the way that humans learn, to perform tasks autonomously, and to improve their performance and accuracy through experience and exposure to more data.[46]

The aim of the EDPS inquiry was to understand “the lawfulness of data processing activities taking place in this context and of the safeguards put in place to address the data protection risks linked to the use of machine learning tools.”[47] It appears that it did not reach the level of understanding hoped for:

We requested, on several occasions, detailed information about the policies in place; the appropriate legal basis for the processing operations; the safeguards put in practice to protect individuals’ personal data; and the specific projects that were at this point carried out by Europol. The replies and information sent to us were not considered satisfactory.[48]

This inquiry was subsequently merged with another one. In October 2020, perhaps wary of the admonishment on the “big data challenge” issued by the EDPS the previous month, Europol officials had requested an informal consultation on the use of machine learning techniques.

Europol wanted to use machine learning techniques for the “operational analysis” of large datasets shared with the agency by national law enforcement agencies. It seems likely that the data in question related to the Encrochat[49] or SkyECC[50] cases.[51] In those cases, law enforcement authorities hacked and/or bugged two encrypted communications services to gain access to large quantities of messages (in the SkyECC case, police reportedly obtained around one billion messages[52]).

Through the use of machine learning, Europol aimed to facilitate “the pre-selection, for review and assessment, of communications or users of these illegal communications.” The development of machine learning models would “help the selection of messages that could be of higher relevance” for investigators.

While Europol officials had sought an informal consultation with the EDPS, exchanges between the two sides led to the EDPS opening a formal consultation procedure in February 2021. The following month, the EDPS issued an opinion on the topic.[53]

The opinion described Europol’s explanation of the proposed data processing as “often incomplete,” and “completely lack[ing] any description of the processing operations. This is problematic as this is the foundation for the rest of the prior consultation process.” It notes that the information shared by Europol:

…does not allow the EDPS to sufficiently understand the full effects of the new processing operations in detail, from the selection of models, to the use of the operational data, including how all the processes are monitored.[54]

The opinion also raised potential issues with the necessity and proportionality of the use of machine learning; with the data minimisation principle; and risks related to bias, statistical accuracy, errors and security. It concluded by saying that the EDPS was unable “to assess whether the notified processing operations comply with the provisions of the Europol Regulation.” Europol was requested to implement an array of measures set out in an action plan and a letter, though these remain unavailable to the public.

One action that did follow the EDPS opinion was the introduction of a specific policy on machine learning for operational analysis. This was signed off by the agency’s Management Board in June 2021. It defines operational analysis as a process by which:

…personal data is used specifically to determine operational action against (a group of) individuals in relation to one or more criminal offences, which may include the seizure of goods, the arrest of suspects and the deployment of investigative techniques to collect evidence.[55]

The policy states that it does not cover techniques such as predictive policing or automated decision-making, nor the use of machine learning used in or developed for research and innovation projects.

The policy requires that any “use and development of machine learning tools for the purpose of operational analysis shall be necessary and proportionate,” and goes on to explain how these two requirements can be assessed and met. It goes on to do the same with the principles of data minimisation, data bias, data accuracy, human intervention, data retention and data security. It also includes provisions on auditing and includes a “by no means exhaustive” list of unacceptable uses of machine learning tools.

Large parts of the policy, which was released to Statewatch in response to an access to documents request, are censored, making it difficult to fully assess its comprehensiveness. However, the fact that it was only released in response to a formal request is noteworthy.

“The development and use of machine learning tools is considered as a form of application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) entailing a number of risks to the fundamental rights and freedoms of individuals,” says the policy. Keeping it locked away until a request was made for its release, and then censoring substantial parts of it, does nothing to aid scrutiny of it.

3.2.3 Facial recognition

More recently, Europol has sought data protection advice on a new facial recognition system it planned to use. In mid-October 2023, the EDPS received a request from Europol for a prior consultation on a “Face Recognition Solution” based on the corporation NEC’s NeoFace Watch system.[56]

As with the “big data challenge” and the introduction of machine learning techniques, the need for a new facial recognition system was premised on the growing amount of data informing Europol’s work. While the agency had been using a facial recognition system known as “FACE” since 2016, new technology was acquired due to the rising volume of requests for assistance from “Europol’s stakeholders,” says the EDPS opinion.

NEC markets the NeoFace Watch system on the basis of its ability to be used in real time. “Faces of individuals are captured and extracted from the video feed and quality matched in real-time. NeoFace Watch software is able to process multiple camera feeds extracting and matching thousands of faces per minute,” say the company.[57] However, Europol uses the system on images and video transmitted to it post facto, and not on live video feeds. The system can also be purchased with a machine learning component, though Europol did not acquire this.

Although large parts of the EDPS opinion released to Statewatch are censored, it appears evident that the data protection impact assessments drawn up by Europol were insufficient. For example, while the agency said it aimed to use facial recognition for three different purposes, it only included an assessment for one of these, operational analysis.

In relation to this issue, the EDPS concluded it was “necessary for Europol to specify the categories of individuals for whom facial recognition will be used” in Europol’s portfolio of Analysis Projects. These sit within the Europol Analysis System and “focus on certain crime areas from commodity-based, thematic or regional angles, e.g. drugs trafficking, Islamist terrorism, Italian organised crime.”[58] Failing to specify on whom facial recognition would be used “creates risks of non-compliance with the principle of purpose limitation,” the EDPS noted.

Europol also intended to use facial recognition for the purposes of cross-checking and for determining whether data it received was relevant to its work. The former involves searching through Europol’s repositories to see if information received is connected to other information held. The latter concerns the type of data processing that underpinned the “big data challenge,” examined above.

In both cases, the EDPS was damning of Europol’s failure to describe how the process would work. This left the EDPS unable to provide an opinion “on whether the intended processing is strictly necessary and proportionate for this purpose.” Failing to assess the necessity and proportionality of the proposed processing would risk “incompliance with the conditions of strict necessity and proportionality” set out in the Europol Regulation.[59]

The EDPS thus recommended that Europol undertake the relevant assessments of necessity and proportionality. The opinion also called on the agency to set out the categories of individuals in Analysis Projects to whom facial recognition would be applied. A “pilot project” approach to the NeoFace Watch system was recommended, “to allow evidence-based decision-making”. The results of that pilot project should be submitted to the EDPS.

The EDPS also sought further information on the accuracy of the NeoFace Watch algorithm for children under 12; to set out a plan for migrating images from the FACE system to the new system; and make sure that when images were deleted from NeoFace Watch, they could not be recovered.

There are several other issues mentioned in the EDPS opinion that were not examined in any more detail by the supervisory authority. The opinion notes that documents provided by Europol mention “the possibility to query external systems (such as those hosted by eu-LISA) with facial images,” but its data protection impact assessment did not examine this matter.

Despite noting that “the possibility to query external systems or to open Europol’s database to external queries considerably increases the impact of the processing on data subject’s rights and freedoms,” the EDPS did not investigate further.[60]

3.2.4 Data protection and European policing

Europol’s frequent requests for assistance from the EDPS to comply with the law will no doubt be seen as welcome by many. Indeed, the EDPS was appointed as supervisor of Europol’s personal data processing “to ensure strengthened and effective supervision.”[61] However, the documents analysed here indicate multiple shortcomings in Europol’s own data protection assessments. Whether or not the agency complied with the recommendations issued by the EDPS remains unknown, as this information is not made public.

Beyond this, however, there are structural questions that arise following the changes to the Europol Regulation that came into force in June 2022. As the EDPS itself has noted:

The amendments to the Europol Regulation… have shifted the balance between data protection and Europol’s operational needs, as it expands considerably the Agency’s mandate regarding exchanges of personal data with private parties, the use of artificial intelligence, and the processing of large datasets. We believe that these changes heighten the risks to individuals’ personal data.[62]

This highlights the political problem underpinning the changes to the law: governments and MEPs felt it appropriate to retroactively legalise prohibited practices.

The resource constraints on both EU and national data protection authorities leave many of them unable to fulfil their statutory duties.[63] In this context, it is hard to see how the promise of “strengthened and effective supervision” of an increasingly powerful agency can be met. This problem will become increasingly acute as Europol continues to acquire ever more data, and as it moves into the business of developing its own artificial intelligence tools and technologies, an issue examined further in section 4.

It should also be noted that even if the data protection regime for the agency were to function as intended, it would do nothing to alleviate the structural role of the agency in policies that cause widespread harm to groups and individuals – a political question that goes far beyond issues of data protection, and which requires a more fundamental reassessment of whether, where and how social issues should be treated as questions of criminality.

3.3 Frontex

Frontex is responsible for ensuring the development and implementation of the EU’s model of “European integrated border management” (EIBM). Amongst other things, this requires “the use of state-of-the-art technology including large-scale information systems.”[64]

As has been well-documented, this includes the use of technologies such as surveillance drones. In the Mediterranean, drones are used to spot boats departing from southern Mediterranean countries – such as Libya and Tunisia – so that the so-called Libyan Coast Guard can be directed to intercept them.

Many of the people intercepted will face “systematic and widespread abuse when forcibly returned to Libya.” Frontex is directly complicit in these human rights violations through its surveillance operations.[65] New technologies thus play a key role in further cementing the EU’s violent and harmful system of border management.

The AI Act requires that AI technologies should not “infringe on the principle of non-refoulement,” or be used “to deny safe and effective legal avenues into the territory of the Union, including the right to international protection.”[66] It remains to be seen whether this legal provision will lead to any change in current practices.

Every year, the agency’s management board decides the amount of technical equipment that will be needed for the agency’s operations, which can take place at EU and non-EU borders.[67] Equipment ranges from “lethal and non-lethal weapons” to binoculars, heartbeat detectors, cars and vans, drug and explosives detectors, and a host of systems for air, land and sea surveillance.[68]

Forms of AI will become increasingly integral to many of these tools and technologies, and the agency explicitly aims to increase the use of AI in its work. Indeed, tools for verifying travel documents are regulated as a form of AI under the Act, though they are not considered high-risk.[69] Frontex has also explored, with other EU agencies, ways to use AI for more intensive screening and monitoring of travellers.[70] In EU-level fora for advancing the use of AI, the agency has referred to one specific use case.

3.3.1 AI in the maritime domain

At the first meeting of eu-LISA’s Working Group on AI in May 2021, a Frontex representative was noted as saying that “one of the key areas is the maritime domain. Proof of concept has been conducted and capabilities have been procured and implemented.”[71] There is no further information provided, but this may be a reference to the agency’s procurement of the services of Windward, a company promising “predictive risk insights” for “proactively identifying behavioral [sic] patterns and uncovering hidden threats.”[72]

Windward was founded by two former officers in the Israeli navy. One of them, Ami Daniel, has said that the company’s software “can take all the shipping information on vessels, cargos, and companies, and put that together with one dynamic view of risk, and a profile of activity.”[73] Since December 2021, it has been listed on the London Stock Exchange.[74]

At the end of 2020 Frontex awarded the company a contract worth €2.6 million, with the possibility to renew it up for up to a further three years.[75] Windward also signed a one-year contract worth €3.2 million with the Greek government towards the end of 2023.[76] Even if the contract with Frontex were extended to the maximum length possible, it should by now have expired. It is unknown if the company is still providing services to Frontex. The EU has been seeking to develop its own AI tools to analyse and predict maritime traffic and vessel behaviour, through the PROMENADE project,[77] in which Frontex has taken an active interest.[78]

3.4 EU Asylum Agency

The EU Asylum Agency (EUAA) was established in 2021, and is the successor to the European Asylum Support Office (EASO). It is tasked with supporting member states in their implementation of EU asylum law and policy, including through “effective operational and technical assistance.”[79]

This can include the deployment of “asylum support teams” to aid in interviewing of asylum-seekers, or to provide interpretation services. These teams may be deployed alongside Frontex and Europol officials in areas designated as “hotspots” by the EU, thus enabling deployments of additional border guards, police officers and asylum officials.

EUAA officials deployed in Greece have been accused of “routinely fail[ing] survivors of pushbacks and survivors of human trafficking,” accusations which are the subject of an ongoing European Ombudsman inquiry.[80] EASO, the predecessor agency, was the subject of similar accusations.[81]

The agency has declared its interest in “the potential and challenges of artificial generative intelligence and applied machine learning,” and plans to work with other EU agencies “to leverage these and other technological innovations.” A role is seen for using AI in “collecting and analysing data and offering support functions for asylum procedures and reception services.”[82] One specific project is currently pursuing these ambitions.

3.4.1 Automated dialect recognition for asylum applicants

In September 2023, the EU Agency for Asylum (EUAA) announced its intention to develop a “Common European platform to identify the country of origin of [asylum] applicants through language assessment.” It has been given name CELIA: Common European Language Indication and Analysis.

Using AI technologies to determine people’s nationality would be given primacy over human assessment. Language and dialect analysis by human specialists would be relegated to the “second-line.” A pilot project “demonstrated that the model is feasible and can be implemented in practice,” and EU member states “expect the EUAA to play a central role in the establishment of a European system.”[83]

The first phase of the project runs from 2024-27 and will be undertaken by the Dutch authorities, with financial backing from the EU’s Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF). This phase will focus on “Arabic dialects only.” It aims to:

- validate “(semi-) automatic language analysis” techniques;

- develop training and selection procedures for human analysts; and

- produce a report on the legal and technical requirements for implementing the system.[84]

The academic Cecilia Manzotti has offered a preliminary assessment of some of the issues raised by such a tool. In her view, in the context of the new asylum and migration laws being introduced by the EU, there are substantial risks for individual rights.

All asylum applicants will be subject to a “screening” process under the new rules. This aims to identify applications that are likely to be considered inadmissible or unfounded, and to refer them to accelerated procedures with fewer safeguards.

Manzotti concludes that:

…the use of an AI language recognition tool to establish asylum seekers’ country of origin during the pre-entry screening would not be without consequences on the credibility assessment of asylum seekers’ nationality claims…

…combined with the systematic channelling of applicants from certain countries of origin into the border procedure [an accelerated assessment procedure], the use of automatic language indication would compromise the applicants’ right to seek asylum. With their asylum applications being examined at the border and under limited procedural guarantees, applicants identified as originating from certain countries would face significant obstacles asserting their claim and challenging the first instance authorities’ decision.[85]

3.5 Eurojust

The use of AI in the field of criminal justice is increasing at both national and EU level. The EU action plan for e-Justice includes a specific action on “Artificial Intelligence for Justice.”[86] A number of EU reports have explored the potential uses of AI technology in the criminal justice area. These are outlined in Annex II to this report. Amongst the potential use cases are:

- automated document processing, for example by extracting and sorting relevant information;

- automated production of case law summaries;

- biometric recognition technologies for tracking individuals across video, photo or audio evidence; and

- automated anonymisation of personal data in evidence.

In December 2024, the EU Justice and Home Affairs Council, made up of member states’ justice and interior ministers, agreed a set of conclusions on AI and justice systems. The conclusions emphasise that “final decision-making must remain a human-driven activity.” However, they also note with approval that judicial decision-making can be supported by AI.

In order to propel the development and uptake of AI technology in the justice sector, the conclusions call on the European Commission to create a “Justice AI Toolbox”:

…a repository of AI use cases (in particular, actors, scope, target, purpose, functionality, scenarios, expected benefits) and tools in the justice sector. The AI tools to be included in the toolbox, whether developed with or without EU funding, could be made available to all Member States.[87]

Even if final decisions in the judicial sector are made by humans, the use of AI technologies for justice – whether criminal or civil – poses enormous procedural and substantive risks. The AI Act prohibits judicial authorities using AI systems for “researching and interpreting facts and the law and in applying the law to a concrete set of facts, or to be used in a similar way in alternative dispute resolution.”[88] However, there are multiple other ways AI systems can be used within judicial procedures, and the EU is evidently keen on exploring them.

While many such systems are being developed and deployed in member states, the EU’s judicial cooperation agency, Eurojust, will also host and use AI technologies. Eurojust’s main task is to “support and strengthen coordination and cooperation between national investigating and prosecuting authorities” in relation to various criminal activities[89] affecting two or more EU member states.[90] It can act in response to requests from member states, on its own initiative, or following a request from the European Public Prosecutor’s Office.

Unlike other EU justice and home affairs agencies, Eurojust’s current work programme makes no specific mention of AI. However, it does make a commitment to “continue to improve our digital infrastructure.” There is at least one specific initiative at the agency making use of AI technology.

3.5.1 Joint Investigation Teams platform

Legislation approved in 2023 will see the EU’s judicial cooperation agency, Eurojust establish a new IT platform for “Joint Investigation Teams” (JITs). JITs are made up of “the competent authorities of two or more Member States” who wish to “carry out criminal investigations in one or more of the Member States setting up the team.”[91]

The platform is supposed to improve cooperation and coordination between members of JITs. It will incorporate “functionalities required for the coordination and management of a JIT,” including AI technology. At a minimum, it will provide a system for “machine translation of non-operational data” – that is, data concerned with financial and administrative issues.[92]

This is the only form of AI mentioned specifically in the legislation establishing the platform. At least on the surface, it seems to pose limited issues in relation to fundamental rights, particularly in relation to other forms of AI that could be used for criminal justice purpose.

There were initial suggestions that a revamped JIT platform could use AI for “analysis of unstructured data (e.g. named entity identification), analysis of different types of audio-visual media for the identification of crime victims or perpetrators, etc.”[93] It remains to be seen whether these will be developed and incorporated into the platform. A 2021 meeting report indicates that JITs were to be given access to a system developed by Europol for the same purposes.[94]

< Previous section

2. Cop out: security exemptions in the Artificial Intelligence Act

Next section >

4. Building the infrastructure

Notes

[1] More detailed information on each system is available in an interactive map produced by Statewatch: EU agencies and interoperable databases, https://www.statewatch.org/eu-agencies-and-interoperable-databases/

[2] ‘Automated Suspicion: the EU’s new travel surveillance initiatives’, Statewatch, July 2020, https://www.statewatch.org/automated-suspicion-the-eu-s-new-travel-surveillance-initiatives/

[3] List of third countries whose nationals are required to be in possession of a visa when crossing the external borders of the member states, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32018R1806#anx_I

[4] List of third countries whose nationals are exempt from the requirement to be in a possession of a visa when crossing the external borders of the member states for stays of no more than 90 days in any 180-day period, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32018R1806#anx_II

[5] For a detailed overview, see: ‘Content of and access to the CRRS’ in ‘Frontex and interoperable databases: knowledge as power?’, Statewatch, February 2023, https://www.statewatch.org/frontex-and-interoperable-databases-knowledge-as-power/

[6] Ibid.

[7] The report was produced as part of Lot 1 of the Framework Contract on the Transversal Engineering Framework (TEF), procured by Frontex and eu-Lisa in October 2020. See: ‘LISA/2019/OP/01’, https://ted.europa.eu/en/notice/-/detail/626975-2020

[8] A previous collaboration between Frontex and Europol also examined developments on this topic: ‘Future Group on Travel Intelligence and Border Management’, Statewatch, 7 September 2021, https://www.statewatch.org/observatories/frontex/access-to-documents-requests/future-group-on-travel-intelligence-and-border-management/

[9] eu-Lisa, ‘AI in CRRS in the Context of ETIAS and Revised VIS Final Report’, 14 November 2022, p.8, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4755/eu-ai-in-crrs-profiling-travellers-final-report-2022.pdf

[10] ‘AI in CRRS in the Context of ETIAS and Revised VIS Final Report’, p.88

[11] ‘AI in CRRS in the Context of ETIAS and Revised VIS Final Report’, p.92

[12] ‘AI in CRRS in the Context of ETIAS and Revised VIS Final Report’, p.95

[13] ‘AI in CRRS in the Context of ETIAS and Revised VIS Final Report’, p.97

[14] ‘AI in CRRS in the Context of ETIAS and Revised VIS Final Report’, p.98

[15] ‘AI in CRRS in the Context of ETIAS and Revised VIS Final Report’, p.101

[16] ‘AI in CRRS in the Context of ETIAS and Revised VIS Final Report’, p.106

[17] eu-LISA, ‘Roadmap for AI initiatives at eu-LISA’, October 2021, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4756/roadmap-for-ai-initiatives-at-eu-lisa.pdf

[18] Ibid.

[19] Recital (1), AI Act, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32024R1689

[20] ‘Council gives green light to the digitalisation of the visa procedure’, 13 November 2023, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/11/13/council-gives-green-light-to-the-digitalisation-of-the-visa-procedure/

[21] Article 2(2)(b), Regulation (EU) 2023/2667 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 November 2023 as regards the digitalisation of the visa procedure, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32023R2667

[22] Article 2(3), Regulation (EU) 2023/2667 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 November 2023 as regards the digitalisation of the visa procedure, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32023R2667

[23] Article 50(1), AI Act, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32024R1689#art_50

[24] Recital (8), Regulation (EU) 2023/2667 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 November 2023 as regards the digitalisation of the visa procedure, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32023R2667

[25] Article 111(1), AI Act, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32024R1689#art_111

[26] Deloitte study for European Commission, ‘Deliverable 3.01: AI Centre of Excellence definition’, HOME/2020/ISFB/FW/VISA/0021, undated, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4757/deliverable-d3-01_-ai-centre-of-excellence-definition.pdf

[27] Deloitte study for European Commission, ‘Deliverable D2.01: Target architecture and design’, HOME/2020/ISFB/FW/VISA/0021, undated, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4758/deliverable-d2-01-target-architecture-and-design-report.pdf

[28] Europol, ‘About Europol’, undated, https://www.europol.europa.eu/about-europol

[29] eu-Lisa Working Group on AI, 1st meeting minutes, 11 May 2021, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4759/annex-10-minutes-1st-wgai-meeting-document-7-_redacted.pdf

[30] ‘Policing in an AI-Driven World’, Police Chief Online, 24 April 2024, https://www.policechiefmagazine.org/policing-ai-driven-world-europol/

[31] Europol, ‘Facilitation of illegal immigration’, undated, https://www.europol.europa.eu/crime-areas/facilitation-of-illegal-immigration

[32] Julie Bourdin et al., ‘The Human Toll of Europe’s ‘War on Smuggling’’, New Lines, 13 December 2022,

https://newlinesmag.com/reportage/the-human-toll-of-europes-war-on-smuggling/

[33] European Commission, ‘Commission reinforces EU rules and launches a Global Alliance to Counter Migrant Smuggling’, 28 November 2023, https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/news/commission-reinforces-eu-rules-and-launches-global-alliance-counter-migrant-smuggling-2023-11-28_en

[34] ‘Europol migrant smuggling proposal torn to shreds by the Council’, Statewatch, 10 May 2024, https://www.statewatch.org/news/2024/may/europol-migrant-smuggling-proposal-torn-to-shreds-by-the-council/

[35] ‘EU: Council's plans for Europol: mass processing of personal data, simplified cooperation with non-EU states, artificial intelligence’, Statewatch, 24 November 2020, https://www.statewatch.org/news/2020/november/eu-council-s-plans-for-europol-mass-processing-of-personal-data-simplified-cooperation-with-non-eu-states-artificial-intelligence/

[36] ‘Policing in an AI-Driven World’, Police Chief Online, 24 April 2024, https://www.policechiefmagazine.org/policing-ai-driven-world-europol/

[37] EDPS, ‘EDPS Decision on the own initiative inquiry on Europol’s big data challenge’, 18 September 2020, https://www.statewatch.org/media/1397/eu-edps-decision-redacted-inquiry-europol-big-data-challenge-10-20.pdf

[38] Annex II, Europol Regulation, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32016R0794#d1e32-109-1

[39] EDPS, ‘EDPS Decision on the own initiative inquiry on Europol’s big data challenge’, 18 September 2020, https://www.statewatch.org/media/1397/eu-edps-decision-redacted-inquiry-europol-big-data-challenge-10-20.pdf

[40] Council of the EU, ‘Information sharing in the counter-terrorism context: Use of Europol and Eurojust’, 9201/16, 31 May 2016, https://www.statewatch.org/media/documents/news/2016/jun/eu-council-c-t-info-sharing-9201-16.pdf

[41] ‘Europol unlawfully processing personal data of vast numbers of innocent people, says report’, Statewatch, 8 October 2020, https://www.statewatch.org/news/2020/october/europol-unlawfully-processing-personal-data-of-vast-numbers-of-innocent-people-says-report/

[42] EDPS, ‘Annual report 2021’, April 2022, https://www.edps.europa.eu/system/files/2022-04/2022-04-20-edps_annual_report_2021_en.pdf

[43] ‘Europol management board in breach of new rules as soon as they came into force’, Statewatch, 3 November 2022, https://www.statewatch.org/news/2022/november/europol-management-board-in-breach-of-new-rules-as-soon-as-they-came-into-force/

[44] EDPS, ‘EDPS takes legal action as new Europol Regulation puts rule of law and EDPS independence

under threat’, 22 September 2022, https://www.edps.europa.eu/system/files/2022-09/EDPS-2022-23-EDPS-request%20to%20annul%20two%20new%20Europol%20provisions_EN.pdf

[45] Appeal in Case T-578/22, 16 November 2023, https://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?text=&docid=281002&pageIndex=0&doclang=EN&mode=lst&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=1499515

[46] IBM, ‘Machine learning’, undated, https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/machine-learning

[47] EDPS, ‘Annual report 2021’, April 2022, https://www.edps.europa.eu/system/files/2022-04/2022-04-20-edps_annual_report_2021_en.pdf

[48] Ibid.

[49] ‘Euro police forces infiltrated encrypted phone biz – and now 'criminal' EncroChat users are being rounded up’, The Register¸ 2 July 2020, https://www.theregister.com/2020/07/02/encrochat_op_venetic_encrypted_phone_arrests

[50] ‘Dutch cops take out encrypted chat service SkyECC; Thirty arrests’, NL Times, 9 March 2021; https://nltimes.nl/2021/03/09/dutch-cops-take-encrypted-chat-service-skyecc-thirty-arrests

[51] There are references in the EDPS opinion to “messages”, “decrypted communications” and a “platform.” It has also been widely-reported that a Europe-wide Joint Investigation Team (JIT) was set up for the Encrochat investigation. The request sent by Europol to the EDPS refers to the use of machine learning “in the context of a specific Joint Investigation Team.”

[52] Daniel Boffey, ‘Colombia’s cartels target Europe with cocaine, corruption and torture’, The Observer, 11 April 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/apr/11/colombias-cartels-target-europe-with-cocaine-corruption-and-torture

[53] EDPS, ‘Opinion on a prior consultation requested by Europol on the development and use of machine learning models for operational analysis (Case 2021-0130)’, 5 March 2021, p.1, https://www.edps.europa.eu/system/files/2022-06/22-03-05_europol-prior-consultation-machine-learning-opinion_redacted_en.pdf

[54] EDPS, ‘Opinion on a prior consultation requested by Europol on the development and use of machine learning models for operational analysis (Case 2021-0130)’, 5 March 2021, p.8, https://www.edps.europa.eu/system/files/2022-06/22-03-05_europol-prior-consultation-machine-learning-opinion_redacted_en.pdf

[55] Europol policy, ‘Development and Use of Machine Learning Tools for the Purpose of Supporting Operational Analysis at Europol’, 11 June 2021, EDOC # 1162317v5, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4760/1162317-policy-on-the-development-and-use-of-machine-learning-tools-at-europol.pdf

[56] EDPS, ‘Supervisory opinion on a prior consultation requested by the European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (Europol) on a face recognition solution’, Case 2023-1104, 20 December 2023, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4761/edps23-12-20_edps_prior_consultation_opinion_en.pdf

[57] NEC, ‘NeoFace Watch’, undated, https://www.nec.com/en/global/solutions/biometrics/face/neofacewatch.html

[58] Europol, ‘Europol Analysis Projects’, undated, https://www.europol.europa.eu/operations-services-innovation/europol-analysis-projects

[59] DPS, ‘Supervisory opinion on a prior consultation requested by the European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (Europol) on a face recognition solution’, Case 2023-1104, 20 December 2023, p.14, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4761/edps23-12-20_edps_prior_consultation_opinion_en.pdf

[60] ‘Supervisory opinion on a prior consultation requested by the European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (Europol) on a face recognition solution’, p.8

[61] Recital (51), Europol Regulation, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32016R0794

[62] EDPS, ‘Annual report 2022’, April 2023, https://www.edps.europa.eu/system/files/2023-04/23-04-26_edps_ar_2022_annual-report_en.pdf

[63] ‘Data protection: 80% of national authorities underfunded, EU bodies “unable to fulfil legal duties”’, Statewatch, 30 September 2022, https://www.statewatch.org/news/2022/september/data-protection-80-of-national-authorities-underfunded-eu-bodies-unable-to-fulfil-legal-duties/

[64] Article 3(1)(j), Frontex Regulation, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32019R1896

[65] ‘EU: Frontex Complicit in Abuse in Libya’, Human Rights Watch, 8 December 2022, https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/12/12/eu-frontex-complicit-abuse-libya

[66] Recital 60, AI Act, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32024R1689

[67] ‘EU: Frontex: equipment requirements for 2023 include “lethal and non-lethal weapons”’, Statewatch, 21 April 2022, https://www.statewatch.org/news/2022/april/eu-frontex-equipment-requirements-for-2023-include-lethal-and-non-lethal-weapons/

[68] ‘Management Board Decision 12/2023 of 22 March 2023’, https://prd.frontex.europa.eu/wp-content/uploads/mb-decision-12_2023-adopting-the-rules-relating-to-te-to-be-deployed-in-frontex-coordinated-activities-in-2024.pdf

[69] Annex III(7)(d), AI Act, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32024R1689#anx_III

[70] ‘EU: Police plans for the “future of travel” are for “a future with even more surveillance”’, Statewatch, 30 August 2022, https://www.statewatch.org/news/2022/august/eu-police-plans-for-the-future-of-travel-are-for-a-future-with-even-more-surveillance/

[71] eu-Lisa Working Group on AI, 1st meeting minutes, 11 May 2021, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4759/annex-10-minutes-1st-wgai-meeting-document-7-_redacted.pdf

[72] Windward, https://windward.ai/industries/gov/

[73] LaToya Harding, ‘Maritime company Windward floats on LSE in first Israeli listing in five years’, Yahoo! Finance, 6 December 2021, https://uk.finance.yahoo.com/news/maritime-company-windward-floats-on-lse-in-first-israeli-listing-in-five-years-145603962.html

[74] ‘London Stock Exchange welcomes Windward Ltd. to AIM’, London Stock Exchange, 6 December 2021, https://www.londonstockexchange.com/discover/news-and-insights/london-stock-exchange-welcomes-windward-ltd-aim

[75] ‘Poland-Warsaw: Maritime Analysis Tools’, Tenders Electronic Daily, 12 January 2021, https://ted.europa.eu/en/notice/-/detail/10370-2021

[76] ‘Greece-Piraeus: License management software package’, 17 November 2023, https://ted.europa.eu/en/notice/-/detail/699946-2023

[77] ‘imPROved Maritime awarENess by means of AI and BD mEthods’, CORDIS, last updated 2 April 2024, https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/101021673

[78] Frontex, ‘PROMENADE: Artificial intelligence and big data for improved maritime awareness, 29 March 2023, https://www.frontex.europa.eu/innovation/eu-research/news-and-events/promenade-artificial-intelligence-and-big-data-for-improved-maritime-awareness-NoxagQ

[79] Article 2, Regulation (EU) 2021/2303 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 December 2021 on the European Union Agency for Asylum, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2021/2303/oj/eng

[80] ‘European Ombudsman opens an inquiry into how the European Union Agency for Asylum addresses allegations of fundamental rights violations in its activities in Greece’, I Have Rights, 17 July 2024, https://ihaverights.eu/european-ombudsman-opens-an-inquiry-into-how-the-european-union-agency-for-asylum-addresses-allegations-of-fundamental-rights-violations-in-its-activities-in-greece/

[81] ‘Greek hotspots: Complaint against European Asylum Support Office to the EU Ombudsperson’, ECCHR, undated, https://www.ecchr.eu/en/case/greek-hotspots-complaint-against-european-asylum-support-office-to-the-eu-ombudsperson/

[82] EUAA, ‘Single Programming Document’, 25 September 2024, https://euaa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/2024-10/SPD_2025-2027_adopted_Sept_2024.pdf

[83] EUAA, ‘Strategy on Digital Innovation’, September 2023, pp.28-29, https://euaa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/2023-10/2023_EUAA-Strategy-on-Digital-Innovation-in-Asylum-Procedures-and-Reception-Systems_EN.pdf

[84] Immigration and Naturalisation Service, ‘CELIA: Common European Language Indication and Analysis - phase 1’, December 2024, https://ind.nl/en/documents/12-2024/flyer-celia.pdf

[85] Cecilia Manzotti, ‘A European language detection software to determine asylum seekers’ country of origin: Questioning the assumptions and implications of the EUAA’s project’, ADiM Blog, November 2024, https://www.adimblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Manzotti_DEF.pdf

[86] ‘European e-Justice Strategy and Action Plan 2019-2023’, Eur-LEX, last updated 12 June 2019, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/summary/european-e-justice-strategy-and-action-plan-2019-2023.html

[87] ‘Council Conclusions on the use of Artificial Intelligence in the field of justice’, 16 December 2024, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-16933-2024-INIT/en/pdf

[88] Annex III, Article 8(b), AI Act, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32024R1689#anx_III

[89] Annex I, Regulation (EU) 2018/1727, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2018/1727/oj/eng#anx_%C2%A0I

[90] Regulation (EU) 2018/1727, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2018/1727/oj/eng

[91] Council Framework Decision of 13 June 2002 on joint investigation teams, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32002F0465

[92] Article 6(a), Regulation (EU) 2023/969 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 May 2023 establishing a collaboration platform to support the functioning of joint investigation teams, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32023R0969#art_6

[93] eu-LISA, ‘Roadmap for AI initiatives at eu-LISA’, October 2021, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4756/roadmap-for-ai-initiatives-at-eu-lisa.pdf

[94] “Another tool is Entity Extraction, which allows the electronic analysis of written text in order to extract identified entities and links by way of the use of Artificial Intelligence. Whilst currently only available internally within Europol, during 2021 the plan is that it will be deployed to external users in the EU Member States and third parties.” See: ‘Conclusions of 16th Annual Meeting of the National Experts on Joint Investigation Teams’, 10 November 2020, https://www.eurojust.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2021-02/conclusions_of_the_16th_annual_meeting_of_the_national_experts_on_jits.pdf

Our work is only possible with your support.

Become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Spotted an error? If you've spotted a problem with this page, just click once to let us know.