Bosnia and Herzegovina: “a society that has gone through a genocide is more prone to it happening again”

Topic

Country/Region

26 September 2025

The Srebrenica massacre remains the only event on European soil since the Holocaust to be formally recognised as genocide - and, in a tale all too familiar, it unfolded as Europe looked on.

Support our work: become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

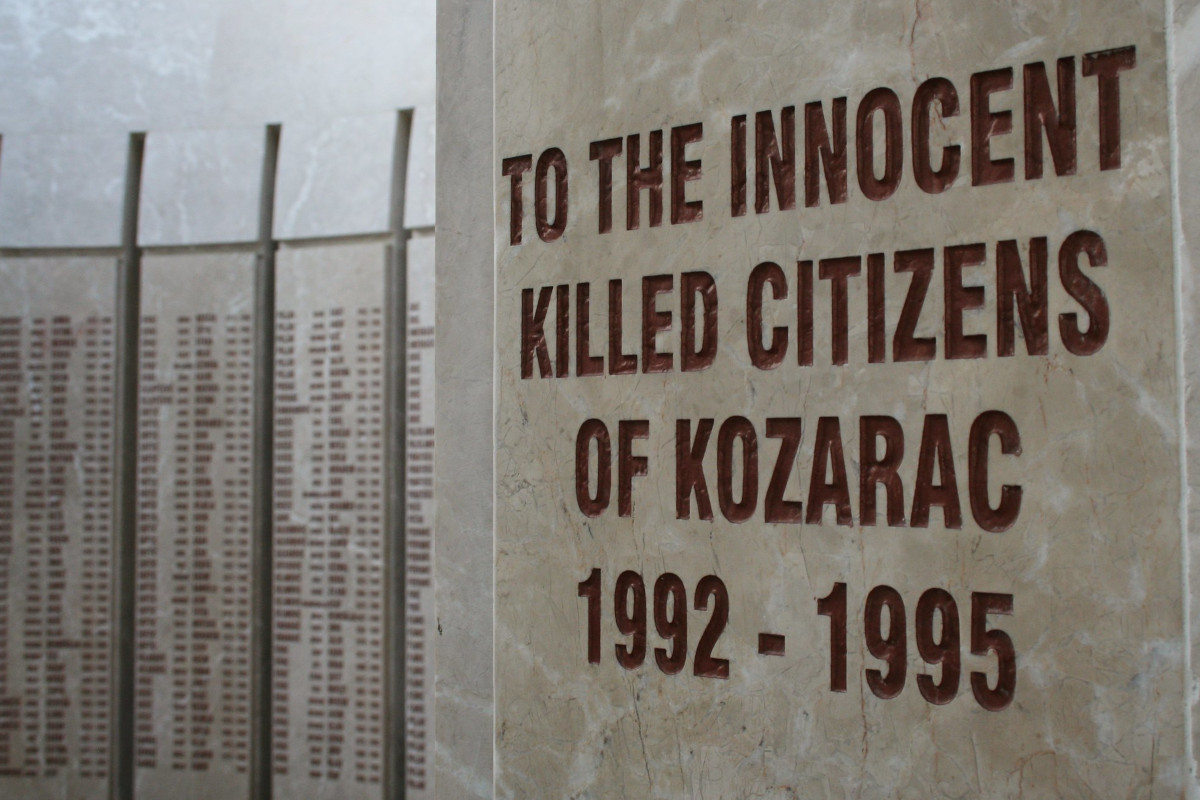

A genocide memorial in Kozarac. Image: The Advocacy Project, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Elmina Kulasić was preparing to start Year 1 when Bosnian Serb forces reduced her hometown to rubble, forcing her and her family into a concentration camp.

"I was seven years old when my hometown was demolished,” she says. “It was actually attacked on my seventh birthday."

Kozarac, a town in northwestern Bosnia and Herzegovina with just over 4,000 residents, was targeted in May 1992 - just two days after Bosnia was admitted as a member of the United Nations and just weeks after declaring independence from Yugoslavia. Over three days, forces loyal to Ratko Mladić, commander of the Bosnian Serb Army, shelled Kozarac relentlessly, attacking it because its population was largely Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim).

Soldiers blared orders from loudspeakers, demanding the surrender of the town’s residents and promising them safety. But when civilians complied, the shelling continued and killed over 1,000 people.

Survivors, including Elmina, her parents and sisters, fled into the surrounding hills, where they slept the night. At dawn, they were rounded up and forced to march on foot to concentration camps. Elmina's family was sent to Trnopolje, previously a local primary school.

Survivors, including Elmina, her parents and sisters, fled into the surrounding hills, where they slept the night. At dawn, they were rounded up and forced to march on foot to concentration camps. Elmina's family was sent to Trnopolje, previously a local primary school.

The irony is not lost on her. "I was being kept in a school at the time when I was supposed to start first grade,” she says. “Except I did not start first grade - I was being starved."

Inside Trnopolje, Elmina describes days "consumed by fear and hunger." Prisoners survived on boiled greens and bread. Classrooms stripped of desks became holding cells where detainees lay on bare floors before being dragged away for interrogation. Elmina, her mother and one sister were kept in one section, while her father and the other sister were held elsewhere in the camp.

“I have vivid memories of where we were placed and the screams I heard when they came in and took certain individuals out of the classroom. Some of the people they took came back, others didn’t," Elmina says.

"We children were pushed into the corners of the rooms we were held in and were hushed by parents. I remember my cousin made a doll from a couple of towels she had, so I played with it - but we never heard any laughter or joy."

An estimated 30,000 people - mainly Bosniaks, but also Croats and Serbs - passed through Trnopolje between May and November 1992. Survivor groups like Prijedor 92 estimate that about 90 people died inside the camp, while prosecutors for the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) argue the number may have been several hundred. Over 3,000 civilians were killed in 1992 in the Prijedor area, which included the camp, according to the ICTY, through mass executions and enforced disappearances.

The UN condemned these crimes in December 1992, describing them as part of “the abhorrent policy of ‘ethnic cleansing’, which is a form of genocide”. It reported being "gravely concerned about the deterioration of the situation in the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina owing to intensified aggressive acts by the Serbian and Montenegrin forces”.

The following year, the organisation declared Srebrenica a "safe area" under UN protection, deploying Dutch ‘peacekeepers’ to guard the enclave. But international protection failed. By the end of the war in 1995, around 100,000 people had been killed in Bosnia - most of them Bosniak civilians. That July, Serb forces overran Srebrenica, killing over 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys in 72 hours.

After a month in Trnopolje, Elmina and her family were moved south to Gračanica, where she began school in 1993. With the help of the Red Cross, the family was later recognised as refugees and fled first to Zagreb, then to Chicago, where Elmina earned two Master’s degrees - in Public Policy and in Human Rights and Democracy.

She says that, with age and education, she came to grasp the full scale of the human rights abuses she and other Bosniaks faced. "The international community could have and should have prevented the war,” she adds. “The Bosnian flag was flying in New York at the UN at the time when it was attacked.”

The Srebrenica massacre was formally recognised as genocide by the ICTY in 2004 and later by the International Court of Justice in 2007. Mladić was convicted of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity by the ICTY in 2017. Yet the wider atrocities committed across Bosnia from 1992 onwards - described by the UN at the time as “genocide” - have never received the same legal designation, being instead classified as crimes against humanity and war crimes.

Bosnia’s central government has officially recognised the events in Srebrenica as genocide, with the country’s parliament designating July 11 as a national day of remembrance for the victims in 2004. But even this recognition is deeply contentious.

In the Serb-majority entity of Republika Srpska (RS), politicians have persistently rejected the legal classification of the massacre, as well as blocking attempts to pass a nationwide genocide denial ban and celebrating in 2021 an outlawed holiday marking Bosnian Serbs' declaration of independence within Bosnia.

Milorad Dodik, who was RS president from 2010 to 2018 and from 2022 to 2025, has been at the forefront of these denials. At a rally in Banja Luka last April, he told thousands of people that while Srebrenica was a “mistake” and a “huge crime” “it wasn’t genocide”. A wider group of Bosnian Serb officials and ethno-nationalist politicians similarly reject the term genocide when it is applied to the broader ethnic cleansing campaign that ravaged Bosnia from 1992.

Asked whether Bosnia has developed a sense of collective guilt and responsibility comparable to post-Holocaust Germany - and to some extent Austria - Elmina Kulasić shakes her head. “We never had a process of acknowledgement that the crimes actually took place,” she says.

“Despite the ICTY and Bosnian Court judgments and despite the fact that the genocide in Srebrenica is the most documented in modern history, survivors are still being put in a position where they have to explain why they were victims in the first place.”

The denial extends beyond Bosnia and Serbia. On April 15, Austria’s national broadcaster ORF aired an interview with novelist and playwright Peter Handke, in which he dismissed the Srebrenica massacre as ‘Brudermord’ (biblical fratricide), refusing to use the term “genocide”. Despite widespread criticism for giving Handke - who has previously expressed these views - a platform, ORF defended its decision.

Today, Elmina works to educate others about the nature of genocide. She collaborates with the Mothers of Srebrenica, an organisation founded in 2002 by Hatidža Mehmedović - who lost her husband and both sons in the massacre - and run by other survivors’ mothers.

"We don't want revenge,” Elmina says, “but we do want the lessons of what happened in Bosnia to be learnt so that they do not happen in Bosnia again, because we know that a society that has gone through a genocide is more prone to it happening again."

Author: Eliana Nunes

Our work is only possible with your support.

Become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Further reading

Participants in Israeli "counter-terrorism" summit must withdraw

State officials planning to participate in a "counter-terrorism" summit hosted by Reichman University in Israel must withdraw, says a statement signed by more than 50 organisations, including Statewatch. The statement says that participation in the event is "particularly unconscionable at a time when, just 80 kilometres away, over two million Palestinians are subjected to constant bombardment and mass starvation."

Will the EU finally stop financing Israel’s genocide in Gaza?

Last Tuesday, the European Commission proposed to partially suspend Israel from its €80bn Horizon science research programme, citing the “severe” humanitarian crisis in Gaza. But this proposal comes late, after years of funding military-linked research with minimal transparency or accountability. As the death toll mounts and Gazans face man-made famine, the EU’s role in bankrolling violence is under scrutiny.

Spotted an error? If you've spotted a problem with this page, just click once to let us know.