EU Council seeks swifter deportations with even lower standards on “safe” countries

Topic

Country/Region

03 October 2025

Discussions are ongoing in the Council of the EU on proposals to establish an EU list of “safe countries of origin” to which people can be deported, and to revise the principle of the “safe third country.” The Danish presidency of the Council, taking into account delegations’ comments, presented proposed new versions of the texts at the beginning of September.

Support our work: become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Image: EU Council Eurozone, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The presidency's compromise texts of the proposed safe third country and safe country of origin rules were obtained by Agence Europe and have been seen by Statewatch.

The legislation on safe countries of origin would estabish a common EU list of countries deemed "safe", meaning asylum applications from citizens of those states can be processed more swiftly and are more likely to be refused.

The safe third country concept, meanwhile, means that a member state applying can issue a negative decision on an asylum application, "claiming that the person can receive protection in a third country"

The presidency has gone to great lengths to accommodate member states’ desire for swifter deportations with less oversight.

Along with the upcoming deportation Regulation, the proposed amendments on safe countries of origin (the ‘SCO proposal’) and safe third countries (‘STC proposal’) are key pillars of the EU’s project of further outsourcing migration management to non-EU countries.

“In general, the Presidency noted strong support from delegations to remove regulatory obstacles in order to allow for a more effective application of the safe third country concept in the future,” reads the explanatory note on the STC proposal (emphasis added).

The key points at issue are:

- the “connection criteria” in EU law, mandating someone may not be deported to a country with which they have no connection;

- the definition of “transit” as regards safe third countries;

- the definition of “arrangement” or “agreement” with an STC, and whether that would limit more informal schemes;

- whether appeals against a deportation order should have an automatic suspensive effect, meaning physical removal is paused during the appeal process;

- whether a country can be considered “safe” if conflict or other dangers persist in certain regions;

- whether EU accession candidate countries should be included in safe country lists as a group or explicitly referred to individually;

- whether, and when, member states are obliged to notify the EU of a deportation agreement made with a third country; and

- to what extent third countries’ subsequent processing of asylum applications must be monitored.

Connection criteria

The European Commission proposed three different options for the “connection criteria”:

- doing away with it altogether;

- leaving member states free to interpret it through their own national laws; and

- providing new definitions of ‘connection’ (including transit through another country before reaching the EU, as well as broader family, linguistic, cultural and “similar” connections).

Noting that “a broad majority of delegations” were in favour of the Commission’s proposals, the Danish presidency proposed to leave options open and allow member states to choose. A German diplomatic cable from July, obtained by Statewatch, said that 13 member states were broadly in favour of this approach.

At the same time, the presidency considers whether an asylum seeker may develop a “connection” with a third country if they have stayed there for a long enough period of time, potentially complicating application of the “transit” concept. This issue is addressed in the expanded possible definitions of “connection”, which now would include countries where “the applicant has settled or stayed”.

‘Transit’ through safe third countries

The presidency has taken into account delegations’ concerns over how “transit” is defined. For instance, if someone has been through an international airport in a given country, that could count as “transit”.

The new wording expands the definition of “transit” to include such situations, provided a person “had the possibility… to request effective protection” without reference to the various reasons someone may not have been able to do so.

“Arrangements” and “agreements”

Member states, apparently anxious not to be limited by technical definitions, argued that the phrase “agreement or an arrangement” in the proposal “should be interpreted broadly”. The presidency has added wording to include both legal and informal schemes.

Suspensive effect

In cases where a person’s asylum application is rejected on the basis of coming from or via an STC, rather than on the individual merits of the application, the Danish presidency proposes wording taking away the automatic suspensive effect of appeals against removal.

There would remain an exemption for cases involving risks of refoulement, though the presidency expressed scepticism about even this: “any refoulement claim with regard to removal to the safe third country is likely to be non-arguable,” says the text. This point will be addressed at future meetings of the Working Party on Integration, Migration and Expulsion (IMEX).

The ‘whole vs part’ problem

On the problem of whether a country can be considered “safe” if conflict or other dangers persist in specific areas, the presidency compromise text suggests exceptions can be made for “specific parts of (the country’s) territory or clearly identifiable categories of persons” who might face danger.

In the case of EU candidate countries, the presidency takes the view that it “may be disproportionate to remove the designation of an EU candidate country completely where an armed conflict is circumscribed to a specific geographical area” and people have access to protection elsewhere in the country.

EU accession candidates

The question of how EU accession candidates should fit into the overall proposals generated considerable debate, particularly whether they should be included in “safe” lists as a group, and whether countries where accession negotiations had been delayed or paused should be included or removed.

The presidency proposes that EU accession candidates “should be considered as safe countries of origin” at the EU level. However, “due account should be taken of the fact that the situation in an EU candidate country could change to the extent that the designation of the country as a safe country of origin should no longer apply.”

Under the presidency’s proposals, if armed conflict (for example) were to break out in a candidate’s territory, then exceptions to the SCO list would “come into effect automatically” and cease when the cause for the exception no longer exists. The presidency proposes the Commission oversee that process.

The presidency proposed exempting accession candidates from safe lists only if accession negotiations were formally suspended. The aim is to avoid a revolving door situation, wherein candidate countries fall in and out of safe lists as accession negotiations stall and re-start.

It is not clear how Ukraine, an EU candidate country currently at war, fits into this larger issue.

Third countries’ asylum processes

The presidency has proposed that STC schemes should only oblige third countries to examine asylum requests “if such requests are made”. The presidency considers people might not apply for asylum in a receiving third country for various reasons, including if they are offered some other kind of residency, or voluntarily depart.

The proposal also appears to leave member states free to decide the process for notifying receiving countries about a deportee’s previous asylum application(s) in the EU. It says that an EU-level requirement to do so “could be an unnecessary administrative burden for the Member States, especially where a safe third country scheme is established on a larger scale.”

Other notable items in the two Presidency texts are:

- With “unanimous agreement among delegations”, the presidency revised the SCO proposal to establish lists based on criteria from the Asylum Procedure Regulation, as previously recommended by the Commission. This list, according to the Presidency, should include Bangladesh, Colombia, Egypt, India, Morocco, Tunisia and Kosovo, as “those countries satisfy the criteria” to be considered SCOs. This does not preclude member states keeping their own lists, or the EU-level list being expanded.

- The Presidency proposes that, in cases where an agreement with a third country is made with both the EU and an individual member state, the former should not limit the latter in making use of “the relevant provisions of both type of agreements”. This is to ensure, reads the presidency’s note, member states can “make full use” of the various STC tools available to them.

- Member states will be afforded some flexibility on when they are required to notify the EU of an STC agreement.

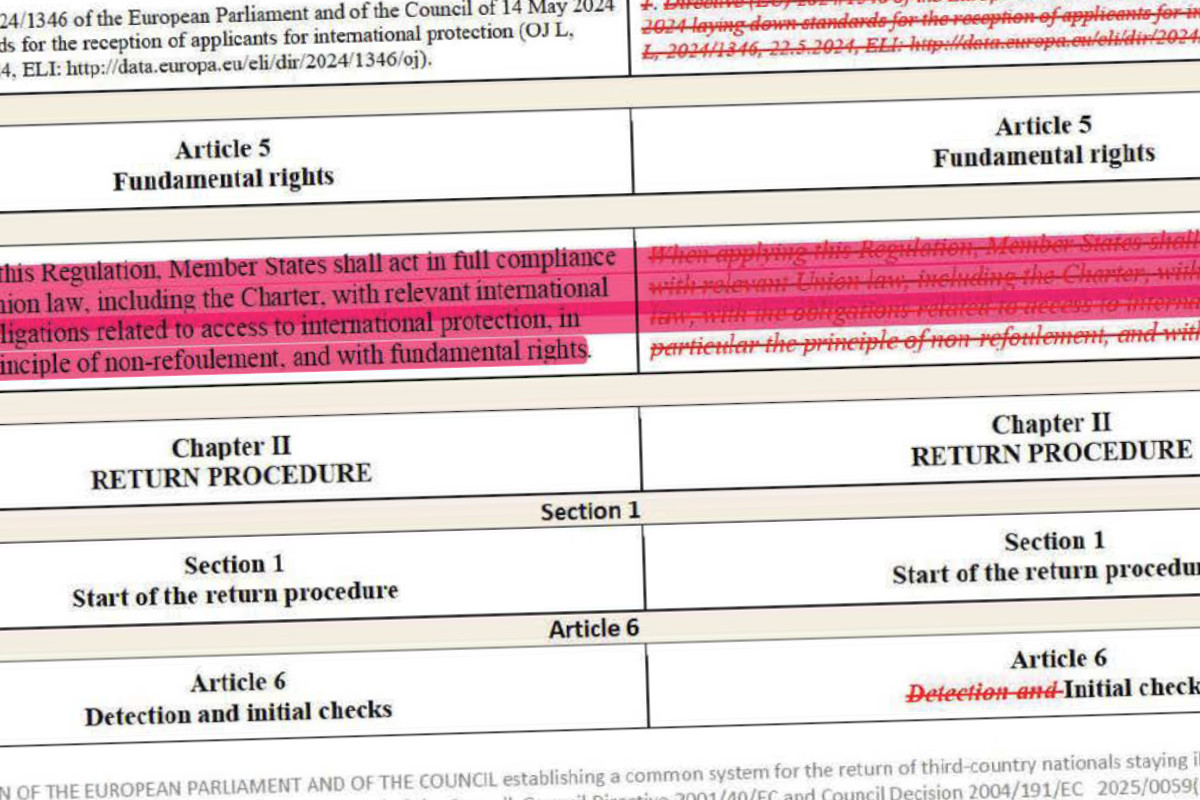

- Where previous proposals had explicit exemptions protecting unaccompanied minors from deportation, the Presidency, believing the desired deterrence effect “would be most effectively reinforced by a provision that applies, in principle, to all asylum applicants” has proposed to remove that explicit protection. Accordingly, the phrase “the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration” has been deleted from the text in the relevant section.

- The presidency also invites delegations to consider what potential there is for new STC schemes to be “circumvented or outright abused” by asylum applicants, or to lead to “an increase in unfounded asylum applications”. By way of example, the presidency envisions people repeatedly arriving in the EU to claim asylum after “the unsuccessful application of the (STC) concept”.

- The new texts leave room for member states to begin applying “accelerated examination procedures” for citizens or residents of countries with an international protection recognition rate under 20%, as provided for in the new pact, before those amendments come into force in June 2026, provided the relevant provisions have been properly transposed to national law.

Our work is only possible with your support.

Become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Further reading

EU wants to deport people to countries with which they have no connection

A German diplomatic cable obtained by Statewatch shows that 13 member states would like to be able to deport people to any country they wish – even if the person has no connection to it. The demands have been accommodated in the most recent version of the proposed law on “safe third countries.” The cable also shows plans to remove the “suspensive effect” of appeals against deportation, while refugee resettlement pledges from member states are lower than ever.

Border externalisation: Deportation law negotiations, EU budget proposals, projects in Africa

The latest issue of our bulletin on border externalisation, Outsourcing Borders, is out now. Including: updates on EU deportation law negotiations; EU budget proposals and external migration control; details on EU projects designed to increase deportations and limit "irregular remigration"; and much more.

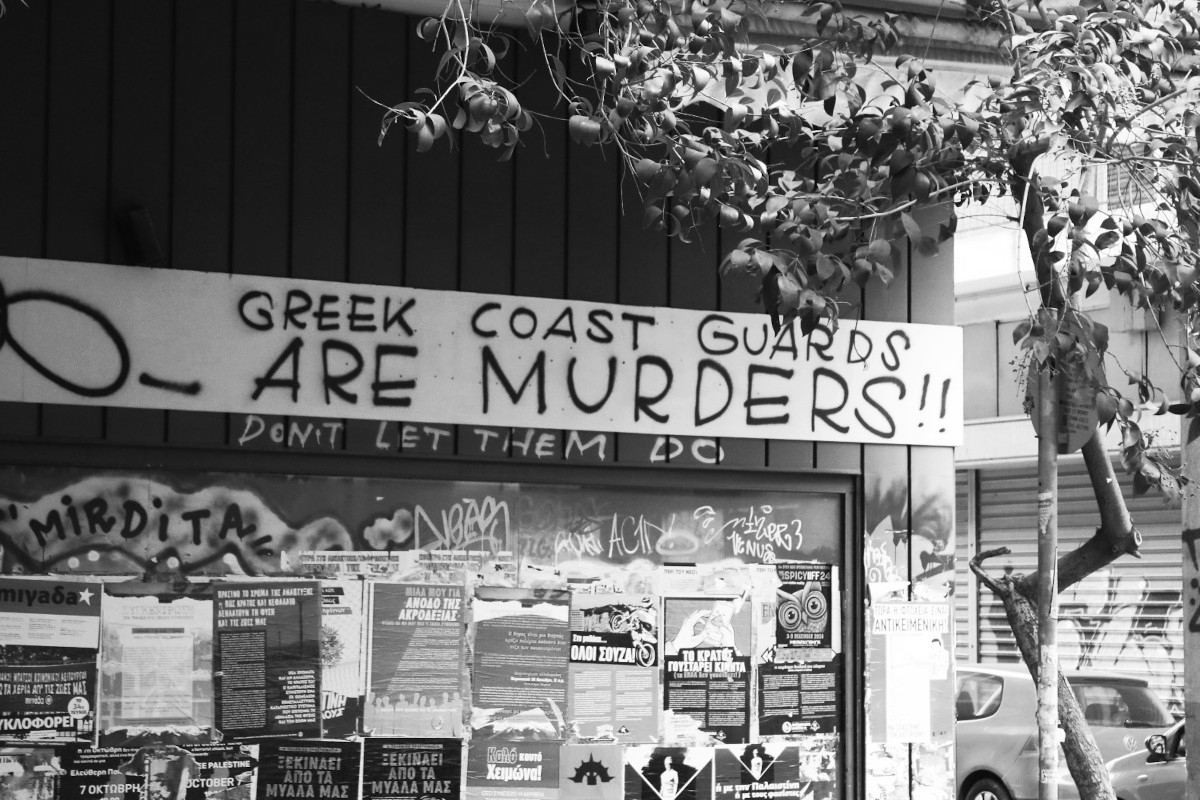

Greece: Illegal, violent deportations: the heavy toll of seeking asylum in Europe

Asylum seekers in Lesvos report that violent pushbacks by masked Greek coastguard forces persist, involving physical abuse, strip searches, theft, and potential use of migrants as auxiliaries.

Previous article

UK: Police footage of protests can be held for decades

Next article

EU deportation proposals: the member states sink to new depths

Spotted an error? If you've spotted a problem with this page, just click once to let us know.