UK: Electronic tagging: the normalisation of a “fascist or totalitarian” technology

Topic

Country/Region

27 June 2025

Electronic tagging has long been a controversial means of monitoring and restricting the movement of people outside of prisons. The British government is expanding the use of electronic tagging against people with criminal convictions, asylum seekers and migrants. A report from 1989, held in the Statewatch Library & Archive, shows remarkably fierce opposition to the practice from what might seem an unlikely source: the Prison Officers’ Association.

Support our work: become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Image: Scottish Government, CC BY 2.0

Technology to solve the “prison crisis”

Last year, four months after coming into office, the government launched a landmark sentencing review that it claimed would end the “prison crisis.”

The review noted that “the prison population has roughly doubled in the last 30 years - but in the last 14 of those years, just 500 places were added to the country’s stock of jail cells.” There are currently almost 88,000 people in prison in England and Wales.

Electronic tagging: a “prison outside prison”

The sentencing review argues that to deal with this situation, “we must expand and make greater use of punishment outside of prison.” This will include “tough alternatives to custody, such as using technology to place criminals in a ‘prison outside prison.’”

In the 1960s, electronic monitoring was developed by two Harvard social psychology students as a way to encourage young offenders to attend events on time. This system rewarded offenders with free haircuts, pizza or concert tickets for attending work, education or drug treatment.

In the years since they were first developed, electronic tags (usually attached to the ankle) have become a tool used by the courts to restrict an individual’s movement at certain times and in certain locations.

Electronic tagging of refugees and migrants

In March this year the government proposed expanding its use of electronic tagging to include asylum seekers and migrants with “limited leave to enter or remain in the UK.”

Electronic tagging of asylum seekers was first proposed in 2003 by former home secretary David Blunkett. He argued: “we can do it in relation to cars. We can certainly do it in relation to people.”

The use of electronic tagging against migrants has been labelled a form of “psychological torture” by human rights organisations, with those forced to wear tags facing serious mental and physical suffering.

It has however been a cash cow for corporations – in particular, G4S and Serco.

In November 2023 G4S were awarded a £175m contract to supply monitoring technology to the Ministry of Justice. In the same month Serco won a £200m, six-year contract from the government for managing electronic tagging in England and Wales

This has come after G4S and Serco were forced to repay the government £100m and £70.5m respectively, after overcharging for tagging devices and services in 2013. This repayment also came with fines of £19.2m and £38.5m respectively, for fraud and false accounting.

“Either fascist or totalitarian”

The use of electronic tags has been repeatedly extended and become increasingly normalised in recent decades. It is still strongly criticised and resisted by campaign groups. Back in 1989, there was also fierce opposition from what might seem an unlikely source – the Prison Officers’ Association (POA).

The POA was founded in 1939. It is the largest union representing uniformed prison and secure psychiatric unit staff in the UK, with more than 35,000 members. It has recently celebrated a government commitment to “extend the use of PAVA, an incapacitant pepper spray to a select number of staff at three youth detention centres in Werrington, Wetherby and Feltham.”

In a 1989 publication held in the Statewatch Library & Archive, the POA described tagging as “associated with either fascist or totalitarian regimes.”

“In a humane and democratic society, such a humiliating and oppressive mechanism is not the proper way to deal with persons who… are to be considered innocent until proven guilty,” the organisation noted, referring to people facing criminal charges.

They also argued that “tagging will require that probation officers become practitioners of surveillance and control” and that “to put an electronic tag on an offender would be a most conspicuous expression of no confidence in that persons [sic] capacity for rehabilitation and reintegration.”

The 1989 publication also foresaw the issue of privatisation. The POA said it was “uneasy about agencies with renowned lobbying capabilities being involved in the most sensitive realm of sentencing policy.”

An “irrelevant gimmick”

“We call on the government to abandon the irrelevant gimmick of electronic tagging,” the POA concluded. “Crime presents Government with a serious and complex problem. Sadly with electronic monitoring the Government have produced an inane and superficial response.”

Times seem to have changed, however. When asked by Statewatch for comment, the POA said that they “acknowledge the benefits of electronic tagging,” though they consider it “morally repugnant to put such an important piece of work in the hands of profiteers.”

A 2022 report by parliament’s Public Accounts Committee investigated the government’s waste of £100m on a scrapped plan to introduce a new electronic tagging system. Importantly, the report concluded that the Ministry of Justice and Prison and Probation Service failed to rigorously evaluate if electronic tagging actually reduces reoffending.

Conclusion: coercive surveillance

The response of the POA to the introduction of electronic tagging in 1989 shows how it was long seen as a tool of “humiliating and oppressive” coercive surveillance.

The current Labour government’s plans to expand electronic tagging demonstrate the normalisation and expansion of British authoritarianism over the past four decades.

These practices, presented by the Home Office as new and technologically innovative are not only dated, but were initially rejected over three decades ago by those working in the very criminal detention system supposed to use them.

Author: Aron Pandian

Our work is only possible with your support.

Become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Further reading

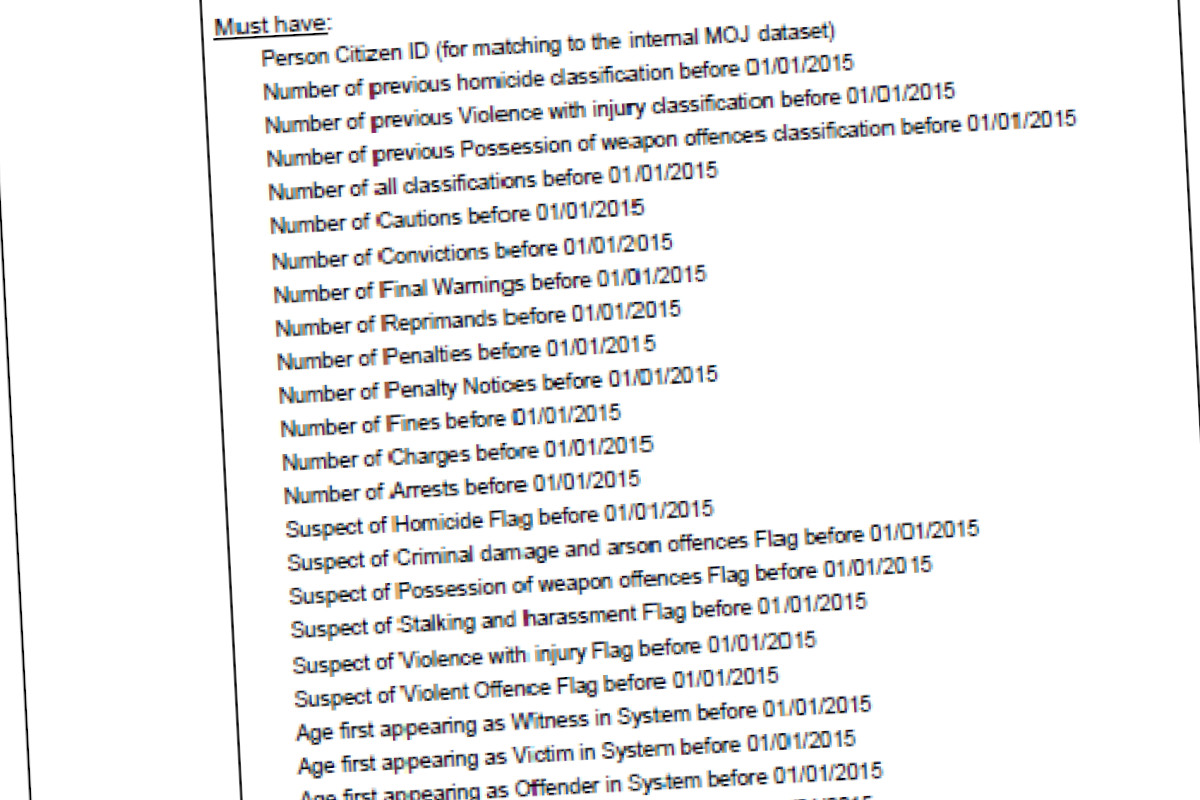

UK: Ministry of Justice secretly developing ‘murder prediction’ system

The Ministry of Justice is developing a system that aims to ‘predict’ who will commit murder, as part of a “data science” project using sensitive personal data on hundreds of thousands of people.

UK: Racist violence does not justify proposed expansion of police surveillance technology

Following the racist pogroms that broke out across England at the end of July and beginning of August, the prime minister, Keir Starmer, announced a range of new policing measures - including a proposal for "wider deployment of facial recognition technology." A letter signed by more than two dozen organisations, including Statewatch, says that an expansion of live facial recognition "would make our country an outlier in the democratic world" and calls for the plan to be dropped.

Spotted an error? If you've spotted a problem with this page, just click once to let us know.