Greece: Illegal, violent deportations: the heavy toll of seeking asylum in Europe

Topic

Country/Region

26 August 2025

Asylum seekers in Lesvos report that violent pushbacks by masked Greek coastguard forces persist, involving physical abuse, strip searches, theft, and potential use of migrants as auxiliaries.

Support our work: become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

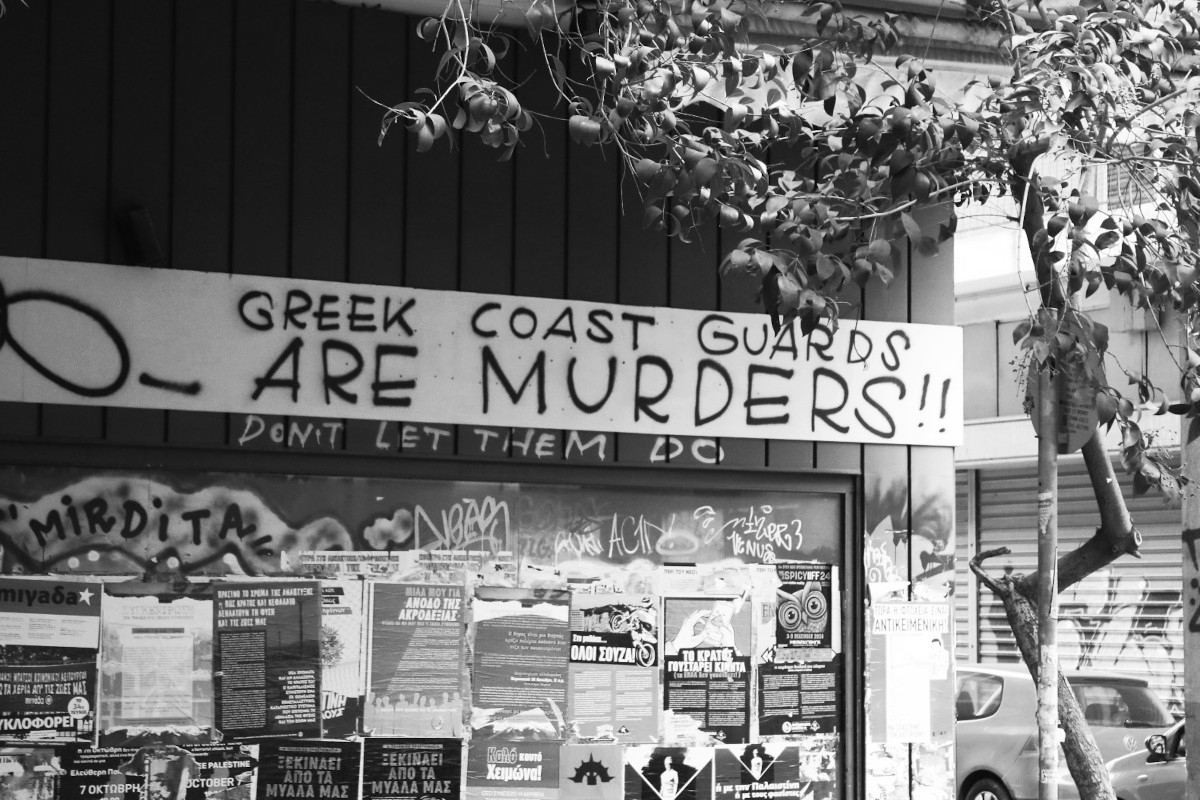

Image: Julia Tulke, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

A special report by Eliana Nunes. Reporting for this article was carried out in summer 2024.

Seeking refuge on the Aegean islands

It's mid-June, and on Lesvos, a Greek island in the north-eastern Aegean Sea, temperatures soar to 35 degrees Celsius.

Just six miles from Turkey at its closest point, the island records the highest number of refugee arrivals in Greece each year and is home to Europe’s largest refugee camp.

Mohamed, a 23-year-old Sudanese man, reached Lesvos in late May. He has asked to use a pseudonym, as he fears that reprisals from the Greek government could jeopardise his asylum status.

Fleeing the civil war in Sudan, by crossing through different tribal areas, was one of the many “hells” he says he endured to reach Greece.

Sea crossings

In February, Mohamed began attempting to cross the sea by boat from Turkey to the Aegean islands.

After four months, during which he was stopped by the Turkish coastguard three times and pushed back by the Greek coastguard three more times, he made it on his seventh attempt.

He shrugs, noting he’s heard worse: his Sudanese roommate at the camp says it took him 17 tries.

From the start of January to the end of July 2024, 4,919 people arrived irregularly by sea on Lesvos. This contributed to a total of 20,784 irregular sea arrivals in Greece during this period, according to data from the UN Refugee Agency.

Mohamed volunteers at the Hope Project, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) in Lesvos, which supports refugees through art and music, as well as providing practical supplies.

Nearby, Abdi, another refugee, whose name has been changed for similar reasons, is frying chips for fellow volunteers. “This is better than KFC,” the 26-year-old Ethiopian says with a smile, gesturing towards the fries.

Abdi fled his hometown, Chancho, near Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, to escape persecution by the government for being a politician of the Oromo Liberation Front.

He began his night-time attempts to cross from Turkey to Greece in July 2023, and reached Lesvos in January – on his 14th attempt.

Each time the Turkish coastguard stopped his boat or rescued him after a pushback by the Greek coastguard, he was detained for up to 20 days for overstaying his Turkish visa.

Pushbacks: forced, informal and illegal deportations

‘Pushback’ is a term that has come to be commonly used as shorthand for forced, informal and illegal deportations of refugees, migrants and asylum seekers.

The practice is associated with the Greek coastguard’s methods of forcing people who have reached Greek territorial waters back towards Turkish waters.

Pushbacks are conducted by authorities in countries across Europe, including Poland, Serbia, North Macedonia, Spain and elsewhere.

Ella Dodd, a lawyer from I Have Rights, a legal aid NGO based on the island of Samos, criticises the term “pushback” as too “sanitised”:

“They [pushbacks] are not simply that someone's taken from one territorial water, or one piece of land and pushed over to the other,” she says.

“There is intense violence, torture, sexual violence, rape, people being stripped, theft, beatings while people are naked, drownings, people dying, people having miscarriages…”

Whatever term is used, the practice violates international laws, including the 1951 Refugee Convention, which prohibits returning refugees to countries where they face persecution.

Violence and abuse near-guaranteed

“Most of the time – 80 per cent – they [Greek authorities] use violence. They beat you. Sometimes they take people back naked,” says Mohamed.

He explains that pushbacks typically take place with unmarked, small speed boats – not just the big Greek coastguard vessels stationed outside the port of Mytilene, the capital of Lesvos.

“They [the Greek coastguard] have small groups who will go with the fast boat. They wear masks. And then this fast boat will be responsible for stopping you in the middle of the sea.”

“If you don't stop, they will beat you terribly,” he says. “Then they get you out and again they beat you.”

On some occasions, his boat driver spoke Arabic and did not understand the masked men’s orders in English.

Masked men speaking Arabic

“Then one of the groups from those pushback people started talking in Arabic… Two minutes, three minutes [later], three of them started talking in Arabic. Then we knew that they [Greek authorities] also use Arabs from Syria,” he says, adding that he believes he has also seen Afghan and African groups.

Though initially stunned by this revelation, he suspects that Greek authorities train “desperate” people to act as “a mafia in the water” in exchange for financial support.

A Human Rights Watch report published in 2022 claimed, based on testimonies, that Greece uses “migrants as police auxiliaries in pushbacks” in the Evros region.

However, the issue has not received media attention since, and there have been no reports of migrants being used in pushbacks on the Aegean islands.

Destruction of boat engines

Mohamed explains that after the men stopped the refugees’ boat, they removed the boat engine and dropped it in the sea.

He notes that the Turkish coastguard similarly destroys the engines of intercepted boats, but that officers remain unmasked, and there is generally no abuse.

The masked auxiliaries of the Greek coastguard then tied the engineless boat to their own and towed it to the coastguard vessel, on which Mohamed and the other passengers were transported closer to Turkish territorial waters.

“When they [the Greek coastguard] see the Turkish [coastguard] is coming, then they run away. They never meet,” he explains.

Left adrift at sea

Near Turkish waters, they were placed on a life raft, relying on local currents to drift the raft away towards Turkey, where they were rescued by the Turkish coastguard.

Twice, Mohamed was just 10 minutes away from reaching Greek land before being pushed back. On one occasion, two passengers jumped off the boat to swim to shore; to his relief, he later learnt that they made it safely.

On 25 May, Mohamed and the 27 others on his boat crossed from Ayvalik, a Turkish coastal town, to Lesvos.

In Lesvos, they trekked for five hours. "I was expecting at any moment that they would push me back, so I didn't feel safe," he says.

When the police arrived, Mohamed, who speaks six languages, acted as the group's interpreter.

“People were really scared. There were some people on the trip with us on that day [who] had reached Lesvos island twice before and they pushed them back,” he says. “They took them, put them in the boats, [and] sent them back.”

The practice of land-to-sea pushbacks was exposed in April 2023 in a viral video published by the New York Times, showing refugees who had arrived on Lesvos being kidnapped by masked men, placed in a van, transported on a speed boat, and abandoned on a raft at sea.

Finding safety

Mohamed, who now works at a hotel in Kos island after having recently obtained asylum, says he is finally “in safe mode”.

Abdi has also received asylum – a right he was denied 13 times due to forced expulsion.

He recounts similar pushback methods to those described by Mohamed, and talks of the theft he faced.

According to Abdi, masked men manhandled him and fellow refugees on his boat, forcing them to remove their clothes in strip searches.

The men confiscated money and mobile phones, which Abdi says that refugees were using to communicate with aid NGOs, including Aegean Boat Report, which documents pushbacks.

"You lose everything to the Greek coastguard," he says.

They then sent the group back to sea, taking them closer to Turkish waters and placing them on a life raft to drift back to Turkey. He points out that only two people were given life jackets by the Greek coastguard.

Death by pushback

As Abdi scrolls through his videos for footage of his rescue by the Turkish coastguard, he pauses on a clip from his recent birthday in Turkey. "You see this guy?” he says, pointing to a man in a video.

“He's dead because of a pushback,” Abdi claims, explaining that he found out about it in late April, while in Lesvos’ camp.

The man is Ashanafi Shambal, a 26-year-old Ethiopian from Nazret, a city southeast of Addis Ababa.

Concerned by a lack of contact, Shambal’s family in Ethiopia reached out to his friends in the Turkish detention centres.

Zelalem Admasu, a close family friend back home in Nazret, says that refugees on Shambal’s boat alleged he drowned after being “pushed off the boat” by “Greek police” in early April.

The allegations of these refugees, currently detained in Turkey, have not been verified. The Turkish coastguard says that Shambal’s body has not been recovered to confirm his cause of death.

The Greek coastguard has faced accusations of drowning people. In June 2024, a BBC documentary revealed testimonies alleging that the coastguard killed 43 people by throwing them into the sea with handcuffs in 15 incidents between May 2020 and 2023.

According to the International Organization for Migration, the Mediterranean has been the deadliest migrant route on record since 2014.

Pushbacks: de facto border control policy after the EU-Turkey deal?

The 2016 EU-Turkey deal aimed to reduce migration to Greece and Europe by returning migrants to Turkey and resettling Syrian refugees from Turkey to EU states. In exchange, Turkey received €6bn (£5.2bn) and visa-free travel for Turkish nationals.

But in March 2020, Turkey announced it would stop preventing migrants from entering Europe; although, in practice, some preventive measures are still enforced.

That year, Greek pushbacks surged. Between January 2020 and 27 July 2024, Aegean Boat Report registered 3,109 pushbacks in the Aegean sea, involving 84,972 people.

According to Marion Bouchetel, a lawyer at Legal Centre Lesvos, an NGO that provides free legal aid to refugees on the island, pushbacks are now “default policy” in Greece.

“It's an exception if you actually manage to cross and take asylum,” she says.

Annina Mullis, another lawyer at the organisation, adds: “Having people say, ‘I tried twice, or three times’ is actually less likely than ‘eight, nine, and ten [times]’” – referencing total attempts, including Greek pushbacks and Turkish preventions.

But Bouchetel warns: “The definition of pushback is that it's a clandestine operation, so there are many that we do not know about.”

Fear of the authorities

Compounding the limited data on pushbacks, refugees who reach Greece are sometimes afraid to speak out.

Rouddy Kimpioka, a refugee from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) who has lived in Lesvos since 2017, says that when approached by a journalist, refugees may think "she’s working for the government. Maybe if I tell her this, I will have a problem with my [asylum] papers."

Pushbacks have not been explicitly addressed or denounced in EU policies.

In April 2025, the European Commission published a paper “on the status of migration management in mainland Greece.”

It made no mention of the practice, aside from an oblique reference to a report by the EU’s Fundamental Rights Agency.

From bad to worse

In fact, human rights organisations are concerned that the new EU Pact on Migration and Asylum, adopted in May 2024, may actually encourage pushbacks.

The pact “does not introduce any specific provisions on border surveillance at sea”, explains Gianluca Cesaro from PICUM, a Brussels-based NGO that supports undocumented migrants.

Instead, it prioritises “migration enforcement (i.e. migrants’ deportations), rather than fundamental rights, such as access to asylum and residence permits,” he adds.

The EU has faced international criticism for allegedly overlooking, and even participating in, Greek pushbacks, through its border and coastguard agency, Frontex.

According to Forensic Architecture, a research group at Goldsmiths, University of London, Frontex directly participated in 122 pushbacks, while having knowledge of 417 more pushbacks between 2020 and 2023.

After criticisms over its operations in Greece, former EU migration commissioner Ylva Johansson insisted that evaluations show “Frontex is doing well”.

Greek authorities have also denied any human rights violations, including pushbacks. When the Turkish coastguard reports on Greek pushbacks, Greek media sometimes dismiss this as Turkish propaganda.

Greco-Turkish rapprochement

Greco-Turkish relations have shown signs of improvement in recent years. In December 2023, Greek prime minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis and Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan met, hailing a new chapter in Greco-Turkish relations.

After their meeting, Mitsotakis claimed that Greece has excelled in reducing “irregular [illegal] migration”.

Dodd from I Have Rights explains, “When I read something stating, ‘we've prevented irregular migration’… It means that the Turkish authorities are trying to prevent people from leaving, but to me this also implies that the Greek authorities are conducting pushbacks.”

“They speak about human rights, but it's all talk”

In spring and summer 2024, the number of arrivals on Lesvos and other Aegean islands was lower than preceding months.

Lawyer Bouchetel attributes this to Greek pushbacks and Turkish preventions, explaining: “After the elections in Turkey and also after diplomatic gatherings between Turkey and Greece, there has been more surveillance at sea from the Turkish coastguard.”

Paris Vounatsis, president of Siniparxi, a Lesvos-based community centre that supports refugees, argues Greco-Turkish border control is a legal grey area exploited by Greek and Turkish authorities to circumvent international laws.

“When there are gaps in the legislation, or when diplomacy allows it, there is always a way to do things that are not legal,” he says.

“And Europe tolerates it,” adds Christina Chatzidaki, a Siniparxi member. “They speak about human rights, but it's all talk.”

Our work is only possible with your support.

Become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Further reading

Pylos shipwreck will "neither be forgotten nor forgiven," says joint statement

"The state crime of Pylos will neither be forgotten nor forgiven." A statement to mark the death of more than 600 people in the 2023 Pylos shipwreck condemns the failure to bring prosecutions against those responsible. The statement, signed by more than 50 NGOs (including Statewatch), notes that "the perpetrators continue to carry out their duties with impunity, not only posing a constant threat to people on the move but also exemplifying the immunity they receive."

Greek border deaths: Frontex management board knew about "systematic" violations

An investigation by the BBC has put the Greek state’s deadly border policies back in the public eye – but there has so far been no mention in the press of Frontex’s operations in the country. Documents seen by Statewatch show that despite warnings from its own fundamental rights officials, Frontex’s senior staff and management board did nothing to halt the agency’s operations in Greece. Suspending or terminating operations is a legal obligation when rights violations “are of a serious nature or are likely to persist.” A case before the Court of Justice of the EU is seeking an order to halt Frontex’s Greek operations, with an appeal filed in January still pending.

Pushbacks, migration policy and returns at the core of EU support for authoritarian regimes

The ongoing debate on pushbacks and rights violations at external EU borders neglects an important aspect: the EU and its states betray their claimed goal to promote human rights, the rule of law and civil society development worldwide by helping authoritarian regimes oppress their citizens, and also to stop them from leaving.

Spotted an error? If you've spotted a problem with this page, just click once to let us know.