4. Building the infrastructure

This report considers two types of "infrastructure" required for the development of the EU security AI complex: institutional and technical. The former is made up various processes, working groups and other ‘spaces’ (whether formal or informal) that have been brought into use in recent years, principally since 2019. The latter consists of the hardware and software needed for the development of new security AI tools and techniques.

Support our work: become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

In this section

4.1 Institutional infrastructure

4.1.1 eu-LISA

4.1.2 The EU Innovation Hub for Internal Security

4.1.3 The European Clearing Board

4.1.4 Frontex

4.2.1 Security Data Space for Innovation

4.2.2 Europol: sandboxes and pipelines

This report considers two types of "infrastructure"[1] required for the development of the EU security AI complex. The first is institutional infrastructure. This is taken to mean the different processes, working groups and other ‘spaces’ (whether formal or informal) that have been brought into use in recent years, principally since 2019.

Understanding this emerging institutional infrastructure is important for understanding the decision-making processes and forms of accountability that currently exist (or not) in relation to security AI. Examining it makes it possible to see which decisions have been taken, when and by whom. The analysis provided in this report is intended to spur further investigation and inquiry, with the aim of finding ways to make decision-making subject to democratic scrutiny and accountability. This is something that, so far, has largely been absent.

Technical infrastructure is taken to mean the hardware and software needed for the development of new security AI tools and techniques. In practice, the distinction between technical and institutional infrastructure may be blurred. Technical infrastructure is hosted and managed by different institutions – for example, as with Europol’s development of a “research and innovation pipeline” (section 4.2.2).

The distinction between institutional and technical infrastructure attempts to provide clarity over different elements of the security AI complex, though no such distinction can be clear-cut. What is evident, however, is that significant time, money and effort is going towards the development of new security AI tools, technologies and techniques. This is a topic that merits political and public interest, inquiry and scrutiny.

4.1 Institutional infrastructure

To embed AI development and deployment within internal security agencies in the EU, new forms of institutional cooperation and connection are being set up. Key to these efforts are the EU Innovation Hub for Internal Security, and a quiet plan to turn eu-LISA into an AI “centre of excellence” in the justice and home affairs policy field.

4.1.1 eu-LISA

Roadmap on AI initiatives

In October 2021, eu-LISA produced a “roadmap for AI initiatives”, which sought to provide “an overview of all existing and future (planned & potential, near to medium/long term) activities of the Agency in the area of AI in the JHA [justice and home affairs] domain.”

The roadmap was always a “draft document,” according to eu-LISA’s press office, as it was never formally adopted by the agency’s management board. However, the agency anticipates updating it once it has adopted a strategy on AI, according to the press office.

The roadmap included 10 initiatives:

- Centre of Excellence for Artificial Intelligence in the JHA domain

- VisaChat proof of concept (PoC) project (see section 3.1.3)

- AI in ETIAS/CRRS

- AI in the shared Biometric Matching System (sBMS)

- European Security Data Space for Innovation

- Supporting the development of AI in the justice domain

- WGAI and transversal activities

- Internal AI Proof-of-Concept (PoC) projects

- AI Testing Lab

- AI Training Activities

Here, we examine the proposal to create a Centre of Excellence on AI. That process began with the establishment of eu-LISA’s Working Group on AI.

Working Group on AI

In February 2021, the then-director of eu-LISA set up a Working Group on Artificial Intelligence (WGAI). This “informal advisory body” was assigned a number of tasks:

- Providing a space for “the exchange of best practices and the discussion on opportunities and challenges arising from the implementation of AI-based solutions within the Agency’s mandate”;

- Identifying “use cases for the implementation of AI solutions in the systems entrusted to eu-LISA”;

- Helping to develop “a common approach for the use of AI-based solutions in the context of the operational management of large-scale IT systems in the JHA domain”;

- Seeking ways to ensure “standardised solutions” were used by “stakeholders” when deploying AI technologies.

Although given a three-year mandate, the group was only in operation for 15 months, during which it met six times. The minutes of its meetings suggest that the WGAI was primarily a space for sharing information. The press office of eu-LISA also put forward this view, saying that the main achievements of the WGAI were “the creation of a forum for exchange of information, leveraged synergies and discussion on the implementation of AI-based solutions”.[2]

The minutes contain extensive notes on different EU and member state initiatives in the field of security AI (the agendas, minutes, and presentations that were used and discussed at the meetings will be published online alongside this report[3]).

However, the minutes also indicate the WGAI also provided a way for member states, EU agencies and EU institutions to coordinate certain policy initiatives, and to consider future possibilities.

For example, the second meeting, held in September 2021, saw a discussion on the results of a questionnaire circulated by eu-LISA to member state authorities. There were responses from 20 member states, mostly “from the Ministry of Interior and Police/Law Enforcement, however, there are some responses also from Immigration authorities and one Ministry of Foreign Affairs.”[4]

The responses indicated that while most member states had national AI strategies in place or under development, there were very few “specific strategies or roadmaps for AI in the area of JHA.” Nevertheless, member states were developing and deploying numerous AI technologies such as automated translation, entity recognition, chatbots, biometric recognition, and video analysis tools. Another “prominently featured topic for AI is big data analytics, like passenger name (PNR) data, passenger profiling and money laundering investigations.”

The survey sought to find out what types of AI technology member states considered it feasible to deploy. “More feasible” were technologies “under human supervision, analysis of internal/seized data, systems that don’t use personal data, biometric recognition in investigations and AI for data analytics for investigations.” On the other hand, unsupervised real-time biometric recognition or automated decision-making tools were considered “less feasible.”

The survey also sought member state views on what types of AI could be used in the large-scale IT systems managed by eu-LISA. Top of the list was the use of AI for “passenger profiling” in systems such as the European Travel Information and Authorisation System (ETIAS), on which efforts are ongoing (see section 3.2.1).

Other topics of interest included tools for predicting busy times at border crossings, “tools for victim identification using various media (voice/image/video),” ways to automatically analyse large datasets, such as Schengen Information System alerts, and detecting fraud in visa applications.

The sixth meeting of the group, in September 2022, discussed the results of a separate survey to member states. This sought to obtain opinions on the different potential uses for AI technology that were identified in a report written for the European Commission by consulting firm Deloitte, entitled ‘Opportunities and Challenges for the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Border Control, Migration and Security’.[5] In particular, it sought to identify “use-cases MS would like to see implemented in the near future.” One of those was the “visa chatbot” (section 3.1.3). All the use cases identified in that report are listed in Annex II to this report.

As well as providing a space to exchange information and coordinate activities between EU and member state agencies, eu-LISA’s Working Group on AI was also supposed to serve as the basis for the AI Centre of Excellence at the agency. Indeed, the creation of the WG was purportedly “the first step” towards the centre.

Centre of Excellence for AI in the justice and home affairs domain

First amongst the initiatives listed in eu-LISA’s AI roadmap was the proposal to create a “Centre of Excellence for AI (AI CoE) in the JHA domain.”[6] This would be “an overarching organisation” to coordinate AI initiatives “in the area of freedom, security and justice.”[7]

The eu-LISA roadmap on AI says the European Commission proposed establishing the AI CoE. However, the roadmap cites a report by international consultancy firm Deloitte as the source for this claim. That report, in turn, includes a legal notice, stating that while it was prepared for the European Commission, “the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.”[8] Whatever the exact origin of the idea, there was no democratic scrutiny or debate involved.

The roadmap goes on to say that to back up its proposal, the Commission’s Directorate-General for Home Affairs and Migration (DG HOME) acquired a more detailed study of what the Centre of Excellence might entail. That study, also carried out by Deloitte, was buried within the VisaChat project (see section 5.1.3).

Rather than set up the CoE in one fell swoop, the aim was to use the VisaChat project as a first step in its establishment:

…whilst defining the end state of the CoE is the main goal, starting the implementation of the CoE from a practical project, i.e. the Visa Chatbot, is desired. In other words, eu-LISA requested Deloitte to propose steps that could be gradually implemented.[9]

Like much of the documentation used in the preparation of this report, the Deloitte study could only be obtained by filing an access to documents request. Its objective was “to provide the reader with an AI Centre of Excellence (CoE) strategy and purpose, establish the CoE’s construct and operating model, and finally define its requirements.”[10]

This was done through “three workshops with eu-LISA and the European Commission (DG HOME) to define the AI CoE’s strategy and purpose, establish the operating model and define the technology requirements.”[11] The study underscores that the aim of the CoE would be to support “the EU JHA community in the development of AI tools and capabilities.”[12] It was proposed to do this by, amongst other things, coordinating “the strategy for AI within the JHA domain, to ensure a cohesive plan of implementation across all stakeholders,” and putting in place “frameworks for future projects to speed up the adoption of AI.”

These objectives have significant, wide-reaching implications, given the potential impact of security AI for the rights and liberties of individuals. It is remarkable that it was considered appropriate to set out the purpose and structure of the CoE on the back of three workshops with just two EU bodies, and no transparency or democratic scrutiny of any kind.

In any event, the initiative appears to have led to nothing. The press office of eu-LISA did not give direct answers to questions from Statewatch on the proposed CoE, but did say: “…should the Member State authorities and the European Commission consider that the creation of a Centre of Excellence for AI is necessary, the Agency will take the necessary steps to do so.”[13]

4.1.2 The EU Innovation Hub for Internal Security

“Cutting-edge products for the security of citizens”

In December 2019, EU member state interior ministers approved a plan for “a joint innovation lab within Europol to harness technological developments and trends, innovation and research.”[14] The aim was for the EU to take “a proactive role” to new technologies, increasing their uptake by police forces.

This led to the establishment of the EU Innovation Hub for Internal Security. The Hub is hosted by Europol’s Innovation Lab, within the agency’s Governance Directorate. It brings together representatives of all the EU’s justice and home affairs agencies, covering “law enforcement, border management, criminal justice and the security aspects of migration and customs.” It also receives input from member state authorities.

The Hub’s mandate was agreed by the Council’s internal security committee (COSI) in early 2020. It should:

…provide a joint EU platform to support the delivery of innovative cutting-edge products for the security of citizens in the EU, with a view to better assess the risks and foster the use and development of advanced and emerging technologies. The Hub will promote a culture of innovation and knowledge sharing across internal security actors in the EU and its Member States.[15]

So far, this has involved agencies involved in the Hub bringing different projects under its auspices, to coordinate support and involvement from other agencies. For example, amongst the “pilot projects” listed in its annual report for 2021 was “EU-coordinated Darknet monitoring to counter criminal activities.” This was led by the EU’s Joint Research Centre, with Europol and the European drugs agency as partners. As outlined below, AI-related projects have consistently been high on the Hub’s agenda.

The Hub held an initial meeting in 17 December 2020, with its first official meeting on 17 January 2021. It hosts an annual event, alongside more frequent internal meetings, and has recently established internal sub-groups (“clusters,” see below) dedicated to particular topics.

Formal membership of the EU Innovation Hub of Internal Security

EU Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA)

EU Agency for Law Enforcement Training (CEPOL)

EU Asylum Agency (EUAA)

EU Counter-Terrorism Coordinator

EU Drugs Agency (EUDA, formerly European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction)

eu-LISA

Eurojust

European Commission

European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE)

Europol

Frontex

General Secretariat of the Council of the EU

The Hub secretariat has made continuous requests for an increased budget and for EU agencies to provide staff, but these do not seem to have been forthcoming. This is despite COSI setting a “requirement to Agencies participating in the Hub to second [provide] representatives,” according to a 2023 report by the Hub itself.[16]

There is clearly a political intention to use the Hub as a central coordination point for the development and use of new technologies in EU justice and home affairs policy, including security AI. That intention seems to have been hampered by financial and staffing limitations. How it develops in the future remains to be seen.

AI projects

According to the Hub’s annual report for 2023, “one of the most discussed topics in the Hub Team meetings was Artificial Intelligence.” In fact, AI projects have been on the agenda of the Hub since it was first launched. Since 2021, it has worked on:

- Accountability Principles for Artificial Intelligence used in the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice (AP4AI);

- Artificial Intelligence in the European Travel Information and Authorisation System (ETIAS) and Visa Information System (VIS);

- Land border pilot project for the Entry/Exit System (requiring the testing of biometric capture and recognition technologies, classified as a form of AI under the AI Act); and

- Technology Foresight on Biometrics for the Future of Travel (a report led by Frontex, published in 2022[17] and examined in more detail in a previous Statewatch report[18]).

The Hub has been reorganised for the 2024-26 period. It has shifted from being organised around ad-hoc projects, to a structure based on a series of “clusters”.

AI “cluster”

One of those “clusters” is dedicated to AI. It was launched in spring 2024. It sits alongside clusters on:

- foresight and key enabling technologies;

- biometric recognition systems: data quality, evaluation and standardisation;

- encryption; and

- knowledge management and innovation in training”

The report outlining the new structure also lists other topics of interest to the Hub: secure communication systems, drones, “virtual/extended reality,” the metaverse, and “privacy-enhancing technologies.”[19]

Following a brief kick-off meeting in March,[20] the first full meeting of the AI cluster took place in April 2024 at Europol’s headquarters in The Hague. It included a session to gain feedback from national members of the cluster on how their governments were implementing the AI Act; presentations on AI tools from the EU’s Joint Research Centre, Europol and the EU Agency for Law Enforcement Training (CEPOL), amongst others; and updates on the CC4AI (Compliance Checker 4 AI) project.[21]

A number of presentations made at the event were released to Statewatch in response to access to documents requests and are published alongside this report.[22] Several of these presentations demonstrate a concern with bias in AI systems. This is a major question for companies, institutions and agencies seeking to use AI technology. However, it has also been argued that this approach misses a more fundamental point.

The academics Agathe Balayn and Seda Gürses have offered an in-depth critique of “debiasing” approaches towards AI.[23] While these approaches will no doubt improve over time, it is hard to see how they can ever fully mitigate biases caused by structural, socio-political forms of discrimination. As Balayn and Gürses note:

…the technocentric solution of debiasing algorithms and datasets… squeezes complex socio-technical problems into the domain of design and thus into the hands of technology companies.[24]

It may of course be police forces, border agencies or other state institutions seeking to do the “debiasing,” rather than technology companies, but the problem remains the same. Balayn and Gürses were writing in 2021, and referred to debiasing as “a technocentric approach in the making.”[25] Four years later, it has arguably become even more institutionally-embedded, yet it remains an inadequate solution to AI systems produced by and for an unequal, unjust world.

A second meeting of the AI cluster took place in June 2024, and a third in September. It remains to be seen whether the cluster will introduce any form of transparency – for example, by publishing the agendas and minutes of its meetings – or whether this will fall upon researchers and journalists filing requests.

4.1.3 The European Clearing Board

Every EU member state has to designate a national policing body (its “national unit”) to serve as “the liaison body between Europol and the competent authorities of the Member State.”[26] An official must be appointed as the head of that unit. Collectively, those officials are known as the Heads of National Units (HENUs).

In 2020, the HENUs, on the initiative of the German Council Presidency and the German Federal Criminal Police Office (Bundeskriminalamt), agreed to establish a new body called the European Clearing Board (EuCB).[27] This was to provide a way for national police agencies to “directly steer the work of the Europol Innovation Lab,”[28] according to a Europol report.

The terms of reference of the EuCB, obtained by Statewatch via an access to documents request, shed more light on its role and remit. The terms of reference describe its mission: to “connect subject matter experts and investigators/analysts at working level with the aim of translating research results into practice and conveying requirements to the technical and strategic level.” It focuses on “tools, methods and innovative technologies used by police practitioners and supporting experts for data retrieval and analysis in the context of criminal police investigations.”[29]

The overall objective of the EuCB is to provide a way for EU and Schengen states to engage with the Europol Innovation Lab. Specifically, the terms of reference sets out seven aims:

- Channel law enforcement agency needs from the operational level to the strategic level, and vice-versa;

- Act as a central point for exchange of information and ideas on “innovative solutions” already in existence and/or use, and that are relevant to law enforcement agencies;

- Discuss the creation of new Core Groups within the Europol Innovation Lab;

- Disseminate the results of Innovation Lab and Core Group work;

- Serve as relay between the Innovation Lab and EU and Schengen member states, and issue non-binding recommendations to the Innovation Lab on its work;

- To establish “a process/methodology for innovation assessment and need evaluation”;

- Identify projects with “cross-sectorial” aspects (that is, not solely related to law enforcement) that could be able at Innovation Hub

The EuCB is supposed to meet at least twice a year, in spring and autumn. These meetings are attended by one representative from each EU and Schengen member state – specifically, those states’ “Single Points of Contact” (SPoC) for the Innovation Lab. These officials can be supported by a deputy.

Meetings of the EuCB can also be attended by a representative of the Innovation Hub’s Steering Committee, and “the portfolio holder ‘Information Management’” of the Heads of Europol National Units (HENUs). Finally, representatives of any third country or international organisation with which Europol has an agreement to exchange personal data[30] can be invited to attend meetings as observers.

The EuCB has also adopted a specific set of rules regarding the establishment and management of Core Groups and Strategic Groups. An annex to the terms of reference states that a Core Group is:

…a working group focusing on a specific tool, project or technology relevant for law enforcement operational work in the EU Member States and the Schengen-associated countries. The result of a Core Group process should be the development of an innovative tool or method for the benefit of the practitioners and investigators of the European law enforcement community.[31]

The EuCB takes decisions on the opening or closing of core groups. Groups should be led by an EU member state or a Europol expert, and require commitment from several other member states. Financing to develop an “innovative tool or method” should “ideally” come from the participating member states. The document also encourages Core Groups to make use of EU budgets such as the Internal Security Fund.[32]

Strategic Groups are focused, unsurprisingly, on strategic topics rather than particular tools or methods. The document gives the examples of “ethics of AI use by LE, communication to the public on AI, or facial recognition, contribution to EU policy and legislation on data spaces etc.”[33] It goes on to say that Strategic Groups “will be used as a forum to express a law enforcement position on specific topics” – for example, the AI Act.[34]

Strategic Groups can be set up on the back of a suggestion from the Europol Innovation Lab or a member state, working through the EuCB. It is left to Strategic Groups themselves to define the timeline and objectives for their work.

The Innovation Lab itself is required to join all Core Groups and Strategic Groups, and to offer them various services. This includes coordination and logistics, a secretariat function, project management support, and communication and information-sharing. Furthermore, the Innovation Lab is supposed to maintain “dedicated thematic networks, comprising law enforcement and academia, research institutes, SMEs and industry,” that should be available to support the groups:

This should lead to co-creation where law enforcement agencies, academia and private sector develop meaningful solutions that enable law enforcement agencies to maximize the benefit of emerging technologies.[35]

Co-creation, however, is more relevant for the Core Groups. The role of the Strategic Groups is to advance the political views of law enforcement agencies – as with the Strategic Group on AI.

Strategic Group on AI

As of 2023, the Strategic Group on AI was being co-led by France and the Netherlands. Amongst other activities, it was lobbying governments to adopt police-friendly positions on the AI Act. According to one Innovation Hub document, these endeavours were successful:

The Group's contribution triggered important changes in the Council position on the AI Act, including on the definition, classification of systems, remote biometrics, use of dactyloscopy and exceptions for law enforcement (mandatory publishing of AI-systems in use or that are developed by law enforcement agencies).[36]

Documents released to Statewatch indicate that the Strategic Group on AI held at least 19 meetings between the proposal of the AI Act and its adoption. The AI Act was an agenda item for all but one of those meetings. It is evident that the group followed negotiations in the Council, between EU member states, closely.

One agenda, from March 2022, notes that a meeting of the Council’s TELECOM Working Party would be “dedicated to LEA [law enforcement agency] related articles.” At the time, the group was working on a “two pager with our position as LEA’s [sic].” On 19 April, the group’s meeting included an update on the outcome of the TELECOM meeting, and in July the group was discussed: “Update on document drafted for WP TELECOM.” The agenda for the group’s March 2023 meeting is the most detailed of those released to Statewatch. It included:

Most important and impactful amendments on the AIA for LEA’s [censored]

Note that there are many changes proposed. Focus on the proposed prohibitions on

- Biometric categorisation in (art. 5.1 ba)

- Removing the exceptions for Law Enforcement in the use of 'real-time' remote biometric identification systems in publicly accessible spaces (art 5.1 d, 5.2, 5.3. 5.4)

- Al systems for individual risk assessment of natural persons or groups, making recidivism estimates, predicting offence occurrence (art. 5.1 da)

- Al systems that create or expand facial recognition databases through the untargeted scraping of facial images (a1t. 5.1 da)

- Categorising emotion recognition systems as High-Risk (Annex III under 1c) and changes in Annex III under 6. related to new prohibitions

And also have a look at recent developments with respect to regulation of generative Al (like use of LLM) and national position in EU countries on these proposed amendments[37]

In June 2023, the group discussed “Impact of the EP [European Parliament] Draft Compromise Amendments on our Position Statements paper,” and in February 2024 there was an agenda item on “Implementing the AI Act.” This appears to have led to the establishment of a separate working group on the implementation of the Act, which was adopted in June 2024. The agenda of the September 2024 meeting, the last one obtained by Statewatch, indicates ongoing engagement with implementation of the Act:

4. Updates Al Act (please also check previously sent information)

a. Guidelines

b. Al Board & subgroups/ Al Office meetings

c. LEWP [Law Enforcement Working Party] / IXIM [Working Party on information exchange for internal security] / COSI meetings

d. DG HOME Expert Group on Al.[38]

Whether the Strategic Group on AI is still active, and in what capacity, remains unknown. What is clear is that the EuCB claims to be responsible – at least in part – for weakening multiple different safeguards in the AI Act, and ensuring exemptions for law enforcement agencies. The documents obtained do not make it possible to verify that claim, but it is clear that significant work was put into trying to influence negotiations.

Needless to say, the EU treaties do not foresee a formal role for police agencies in negotiating new legislation, which is supposed to be a prerogative of the European Parliament and the Council of the EU. That they do so is unsurprising – but it is certainly unfortunate that the EU’s secretive and opaque law-making system makes it essentially impossible for the public to be aware of them.

It is also noteworthy that one of the Innovation Hub’s longest-standing projects is one that has developed a set of “accountability principles for AI.” Alongside these principles, the agency has developed a “compliance checker” – an online questionnaire – to let police forces examine whether a particular technology or technique is in line with the Act and the principles.

What we have here is a form of self-regulation. The use of security AI is subject to certain forms of external oversight and accountability under the AI Act, mainly by national and EU data protection authorities. That oversight is limited by the exemptions contained in the Act, and those authorities are already severely short on funding, staff and resources. The accountability principles and compliance checker provide a basis for arguments that no further external scrutiny or accountability is needed. It should also be noted that while the principles are public, the compliance checking tool is only available to law enforcement authorities.

4.1.4 Frontex

Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, has long been involved in the EU’s research and innovation agenda.[39] In 2019 it received a new role, giving it the power to identify relevant topics for the EU’s security research programme, currently part of the broader Horizon Europe programme.[40]

The intention is for the agency to identify relevant research topics and evaluate proposals for research projects. It then oversees those projects, and aids in the acquisition and use of the resulting technologies and techniques.[41] This specifically includes “the use of advanced surveillance technology.”[42] All its projects revolve around forms of advanced technology, including some classified as AI under the AI Act.

Recent Horizon Europe projects have covered topics such as:

- the use of “cosmic rays” for customs detection equipment at ports;

- systems for maritime surveillance, including underwater surveillance;

- technologies to analyse identity documents and detect fraud;

- “pre-frontier” surveillance systems to monitor activities beyond the EU’s borders; and

- systems to gather open-source data for interpreting foreign nationals’ perceptions of the EU and migration possibilities.[43]

The agency also has its own budget to fund research and other “ad-hoc” projects. These research projects cover similar topics to those funded through Horizon Europe. Recent projects include:

- the development of coastal surveillance systems;

- portable devices for inspecting travel documents; and

- the use of drones to detect “land border violations.”[44]

Its 2024 budget for providing “ad-hoc grants,” whether for research or other projects, was just over €7.4 million.[45] Recent work by Algorithm Watch has investigated many of these research projects in more detail.[46]

As part of its growing role in the EU’s research and innovation agenda, Frontex has developed infrastructure for showcasing and testing new technologies. A new Border Management Innovation Centre (BoMIC) is described by the agency as “a Frontex lab-space designed to strengthen the European research and innovation capacity in the field of border security.”[47]

BoMIC is Frontex’s “innovation lab” and is the unit that participates in the EU Innovation Hub for Internal Security (section 4.1.2). It is intended to host a physical testing and demonstration space, including a 1300m2 “Testing/Tech lab” and a 300m2 “technology exhibition.” This is described in a Frontex presentation as a “key component of the new Frontex HQ.”[48]

That presentation was given at one of Frontex’s many “industry days,” and notes that it will “further enhance” cooperation with the EU’s Joint Research Centre. The key areas of interest for BoMIC are listed as:

- border checks;

- border surveillance;

- border and coast guard equipment;

- command, control, communications, computers and intelligence (C4I);

- training and learning tools; and

- “key enabling technologies” such as computer vision, the Internet of Things (IoT), quantum computing and autonomous systems.

The agency’s most recent programming document, covering the 2024-26 period, makes a number of specific references to AI. However, there are no meaningful details included.

The document says that “automated/AI based tools” will be used to “support” coast guard operations, and to increase sharing of data amongst “coast guard functions.” This is to contribute to the broader aim of increasing information sharing amongst different the different national and EU agencies and units that collectively make up the European Border and Coast Guard.[49]

One of the agency’s strategic objectives for the 2024-26 period is: “Reduced vulnerability of the external borders based on comprehensive situational awareness.” One activity contributing to this objective will be “constant situation monitoring and risk analysis.” One expected result is for “artificial intelligence solutions” to be deployed. Indeed, the use of AI systems is one of the indicators used to measure success.[50]

This means the gathering of large amounts of data, through border surveillance systems and other sources, whether powered by AI technologies or not. The resulting information would be used to inform strategic and operational decision-making: for example, on how many border guards to deploy at sites where refugees are seeking to enter EU territory.

4.2 Technical infrastructure

All artificial intelligence technologies need extensive, and expensive, technical infrastructure to operate. The result is lengthy and frequently destructive chains of extraction and dependency. These run from the mining of the materials needed to create the hardware on which AI software runs, to the data needed to feed the AI software itself, to the disposal of waste electronic equipment.

Some of the most extreme infrastructural requirements come in relation to energy: the company OpenAI, responsible for ChatGPT, “pitched the Biden administration on the need for massive data centers [sic] that could each use as much power as entire cities.” The company argued this was needed “to develop more advanced artificial intelligence models and compete with China,”[51] and companies are already acquiring nuclear power to run data centres.[52] An Executive Order signed by president Biden prior to leaving office introduces requirements for the US state to support further efforts.[53] Influential think tanks are making similar proposals for the UK.[54]

Remarkably, the EU’s AI strategy makes little mention of energy. It merely says the Commission will “support more energy-efficient technologies and infrastructure,” as part of its support for “technologies and infrastructure that underpin and enable AI.” This, the Commission says, will make “the AI value chain greener.”[55] Nor does the AI Act say much on the topic.[56] These limited commitments may be explained by politicians’ and officials’ reliance on the “false assumption that the digital and green transitions are ‘twins’ and always mutually reinforcing.”[57]

There is thus a significant material aspect to the EU’s security AI plans, though it goes completely unmentioned in any of the papers and reports related to those plans. Security AI is certainly likely to require less hardware, processing power, and thus energy than other, more large-scale forms of AI, though the issue remains extremely important. Nevertheless, one aspect of the infrastructure required for deployment of security AI has received substantial attention in policy and planning papers: the need for data.

4.2.1 Security Data Space for Innovation

One of the six political priorities during Ursula von der Leyen’s first term as Commission President was to create a “Europe fit for the digital age.”[58] Under this banner, a host of initiatives were launched, including the Digital Markets Act, the Digital Safety Act, and the AI Act, amongst others.

Underpinning these efforts was the European Data Strategy, announced in February 2020:

The aim is to create a single European data space – a genuine single market for data, open to data from across the world – where personal as well as non-personal data, including sensitive business data, are secure and businesses also have easy access to an almost infinite amount of high-quality industrial data, boosting growth and creating value, while minimising the human carbon [sic] and environmental footprint.[59]

Within this single European data space, there will be a set of underlying “common European data spaces.” These are expected to allow the pooling and sharing of data in different sectors, with a clear emphasis on using that data to develop AI technologies. As the Data Strategy notes:

The availability of data is essential for training artificial intelligence systems, with products and services rapidly moving from pattern recognition and insight generation to more sophisticated forecasting techniques and, thus, better decisions.

According to the European Commission, a data space has five key characteristics:

- An IT infrastructure that is used to “pool, access, process, use and share data”;

- A set of rules that determine the rights and obligations of those that can access the space;

- A requirement for data owners to remain in control of the data they share with the space, and to set the purpose and conditions for re-use;

- The presence of vast quantities of data that can be re-used either for free or for a price, depending on the data owner’s preference;

- Participation by an “open number” of individuals and organisations.

Data lakes are described as repositories of structured and unstructured data at any scale, to which users have unrestricted access. The Commission describes data spaces, on the other hand, as “more like fish markets.” Unfortunately, this analogy is not explained in any more detail.

However, it is evident that the ultimate goal is for data spaces to be made up of separate but interconnected datasets held by different organisations and institutions. Access to that data would be granted to users of the data space on terms set by the owners of the data. Users would be provided tools “to enable discovery, access and analysis across industries, companies, and entities.” This is then supposed to facilitate the training and testing of new AI tools and algorithms, for which centralised infrastructure – for example, computing power or storage – may be required.

Some 20 data spaces have so far been announced.[60] These include health, agriculture, finance, mobility, energy, public administration, and security.

Making space for security

In the data strategy, there was reference to a data space “to address law enforcement needs.” A year later, in its organised crime strategy, the Commission announced the creation of a specific “European security data space that will be key to develop, train and evaluate tools for law enforcement.”[61] It should be “tailored to the needs of security and immigration stakeholders, including national authorities, EU agencies in charge of European security and justice representatives,”[62] although it appears that initially it will only target police forces.

Later rebadged the Security Data Space for Innovation (SDSI), the Commission has outlined a number of supposed benefits. As well as enabling the development of AI technologies, it would increase the EU’s “technological sovereignty,” through the creation of new national and European datasets. This, in turn, would “eliminate the threat of malicious interference of third countries/parties,” reduce the EU’s dependence on foreign companies, allow the EU to set its own quality standards, and “increase the technological capabilities of the national authorities.”

Aims of the Security Data Space for Innovation

The points below outline the “potential added value of the EU SDSI across dimensions,” according to a study carried out by the consultancy firm EY for the European Commission.[63] The text is the same as that in the study, but for ease of reading is not placed in quotation marks.

Trust and competences

- EU SDSI as “one-stop-shop” for innovation in the area of law enforcement. Its aim is to contribute to build trust between LEAs and competences for research and innovation within LEAs [law enforcement agencies].

- LEAs would be invited to use the EU SDSI “at their own pace”, e.g. to obtain information about innovation in LEAs, to get to know and interact with counterparts in other LEAs, to obtain support, to access non-sensitive data that could be used for innovation efforts etc.

- EU SDSI would provide various services to LEAs, depending on need

Access to data

- Access to higher quantity and quality of data for Member States’ LEAs:

- Quantity: Different types of non-sensitive data that LEAs may otherwise not have access to

- Quality: Compliance with agreed standards and principles ensures that data is useful for Member States’ innovation efforts

- Data access in full compliance with EU and Member States’ applicable legislation. Member States should remain owner of their data and decide about its use.

Innovation readiness

- Improved access to data is expected to facilitate Member States’ innovation efforts in the area of law enforcement, in particular with regard to the testing, training, validation, and approval of AI tools

- EU SDSI to focus on specific use cases that are driven by the Member States, e.g. in the area of image recognition, video analysis, etc.

- Member States will remain responsible for their own innovation efforts: EU SDSI is seen as an offer of support to Member States

Improved security

- Improved ability of Member States is expected to facilitate maintaining the high level of security within the EU

- EU SDSI is in principle relevant for all types of LEAs

- Could be developed from covering police to e.g. border guards and/or customs in the future

- Interaction of EU SDSI with other EU-level data spaces and Member State environments as relevant enabler for improved security

- Link of EU SDSI to Europol Sandbox Environment potentially possible: Not only access to non-sensitive data but also improved algorithms based on sensitive data in enclosed facility.

Funding the security data space

In February 2022 a call for proposals under the EU’s Digital Europe Programme[64] was published. The call sought a project to develop the two key requirements for the SDSI. First, a governance model that would define data standards, infrastructure and telecommunication requirements, and so on. Second, the project was “to generate, collect, annotate and make interoperable data suitable to test, train and validate algorithms.”[65]

However, despite the Commission offering up to 50% of an expected €8 million total cost, the plan failed – no proposals were received in response to the call. According to the European Commission, despite strong interest in the idea from member states, they were not in a position “to guarantee sufficient engagement from the relevant national authorities and bring the necessary complementary funding.”[66]

A study by two international consultancy firms, EY and RAND Europe, was used to support the call for proposals.[67] This found that “law enforcement is not a high priority in national AI strategies” and limited uptake or use of “AI-based solutions and data spaces for law enforcement purposes.” It also found that law enforcement agencies make little use of data for innovation.[68] Nevertheless, at a March 2023 workshop hosted by the Commission, “stakeholders agreed that a security data space for innovation is a condition sine qua non for seizing the opportunities of AI and improving access to relevant data.”[69]

At the same time, a call for proposals was published under the Internal Security Fund, which finances policing and security projects. It noted that the SDSI required “incremental development in the coming years.” The call was smaller (with a €1 million budget) and less ambitious than the one published under the Digital Europe Programme. It sought “preparatory work needed for the creation of high-quality large-scale shareable data sets for innovation,” which would include work on data standardisation and anonymisation.[70]

The result was the TESSERA project, which started in March 2024 and consists of seven organisations, including the Spanish interior ministry and the Greek police.[71] It is expected to run for between two and three years. Its specific aims include mapping the types of datasets that could be shared through the SDSI. These include “photos, videos, voices samples, unstructured text (e.g. forums), unstructured hybrid data (e.g. web scraping or emails), structured data (e.g. telecommunication signalisation data).”

At the same time, the project will analyse “technologies that would allow the sharing of operational data, including but not limited to data anonymisation and generation of synthetic data sets, as a possible solution in cases of legal restrictions on collection and sharing of law enforcement datasets.” Other requirements include tools for classifying and annotating datasets, and tools for assessing data quality.[72] It sits alongside similar efforts, such as the Horizon Europe-funded LAGO project.[73]

Whether TESSERA will achieve its goals remains to be seen. It is, nevertheless, evident that developing a European infrastructure for creating new security AI tools and techniques is of significant interest to EU and certain national officials. Whilst the TESSERA project is taking some of the first steps towards developing the SDSI, a related initiative that is likely to contribute to the overall goal is ongoing at Europol.

4.2.2 Europol: sandboxes and pipelines

Europol has been involved in the development of new technologies for a number of years, and the reform of the agency’s mandate in 2022 gave it a stronger role than previously. The best example of this shift can be seen in its relation to the EU’s security research programme, which funds the development of new security technologies. It is currently known as Civil Security for Society and is part of the larger Horizon Europe programme. The agency has been a participant in a number of security research projects over the years. These have primarily sought to develop new big data and machine learning tools for law enforcement agencies.[74]

The new mandate that came into force in 2022 prevented it from participating in those projects. Instead, Europol was given a new remit: to help define priorities for the policing component of the security research programme.[75] Thus, it now has a strategic, agenda-setting influence over the types of investments made by the EU in new police technologies.

Alongside this new role, Europol has also started hosting annual “industry and research days,” much like other EU agencies. These invite private companies, academics and other researchers to present technical “solutions” to law enforcement problems. The first event was held in 2024, focusing on open source intelligence, “emerging platforms,” robotics and AI.[76] The 2025 event has a far broader scope, covering “robots or drones,” quantum technologies, “advanced biometrics for forensic analysis,” open source intelligence for analysing “private channels,” and the use of AI for “target detection, identification and tracking,” amongst other things.[77]

The agency has also launched a series of in-house technical initiatives to develop and make available new tools and techniques, many powered by AI. The agency ultimately aims to create what it calls a “Research and Innovation Pipeline” through which new technologies are taken from the research to the deployment phase. The intention is for many of these technologies to be “data-driven,” and thus there is significant work going into the development of the technical infrastructure needed to develop and test new algorithms. The evidence available suggests that Europol’s efforts in this area may be built upon to create the broader Security Data Space for Innovation.

Strategic research goals

According to an internal document from February 2023, Europol has seven strategic goals with regard to research and innovation:

- strengthen member states’ technological capabilities that allow them “to identify, secure and analyse the data needed to investigate criminal offences”;

- provide software that reduces manual work for police analysts;

- prepare law enforcement authorities for dealing with increasing amounts of data;

- support member states in using emerging technologies;

- assist the European Commission in drawing up the security research programme;

- “drive innovation and reinforce synergies in research and innovation projects”; and

- “play a key role in promoting the development and deployment of ethical, trustworthy and human-centric artificial intelligence.”[78]

The agency is obliged to publish its “planned research and innovation activities” in its multiannual work plan. The document is not particularly revealing. It merely states that “Europol Research and Innovation projects will develop AI tools, trained with data provided by MS [member states] for that purpose, to facilitate investigations.”[79] The document also refers to the development of machine learning tools.[80]

The February 2023 document cited above is more specific about these aims, although it was only published in response to an access to documents request from Statewatch. It lists almost three dozen specific technologies for the automated analysis of images, video, text and audio, as well as tools for data presentation and processing (see Table 1: Europol's priority research topics).

These include topics such as voice print analysis, age and gender detection from audio recordings of voices, and the use of augmented and virtual reality for data analytics. The same document states that “the development, use and deployment of new technologies are guided by the principles of transparency, explainability, fairness and accountability, do not undermine fundamental rights and freedoms and are in full compliance with Union law.”[81]

While this is a worthy aspiration, there is no guarantee that this will be the case. Furthermore, being compliant with the law may not provide as much protection for individuals as might be hoped. As explained in section 4.1.3, interior ministries and police officials helped to water down or remove many of the protections and safeguard that should have been included in the AI Act. The legal standards that must be met by new technologies are thus lower than may otherwise have been the case.

Table 1: Europol's priority research topics

|

Image and video analytics |

|

Pre-processing and preparation, Object detection, Image similarity search, Image classification, Face recognition, Personal features extraction, Fingerprint detection from fingerprints in images, Scene recognition, Scene classification, Indoor and outdoor image and geo-location, Deep fake and image/video tampering detection |

|

Text analytics |

|

Named entity extraction, Link extraction (“automatic extraction of links between extracted entities and presented for corroboration”), Robust translation of informal text, Text classification, Stylometric analysis |

|

Audio analytics |

|

Speech to text in low quality audio, Language detection, Age and gender detection from voice, Voiceprint analysis, Accent recognition in voice |

|

Data representation and processing[82] |

|

Graph Analytics, Clustering in network of nodes, AR/VR (augmented reality/virtual reality) data analytics |

The European Data Protection Supervisor, the body responsible for oversight of Europol’s processing of personal data, has understandably taken an interest in the agency’s new research mandate. Towards the end of January 2024, the EDPS met with Europol officials (the Fundamental Rights Officer, data protection officials, and representatives of the Innovation Lab[83]) to get an understanding of how it was implementing the new provisions, and its research plans.

The EDPS was told at that meeting that the agency was drafting policies and processes to ensure it complied with the safeguards in its Regulation, and that it would inform the EDPS of these in due course. Information on planned projects would also be provided.[84] However, none of this was forthcoming – hence the EDPS letter, which was sent on 1 October, a little more than eight months after the meeting with Europol officials.[85] It requested that Europol provide to the EDPS:

- documents that would allow an assessment of how the agency deals with data protection in research projects;

- whether Europol “has started its research and innovation activities already,” or, if not, when it expected to do so; and

- how the agency was complying with the rules governing the use of personal data in research projects.

A further request in the letter was censored.[86] Europol’s response, which was expected by 23 October 2024, remains unknown.

A digital playground for the police

Officials at the agency were evidently working hard to implement the new research and innovation mandate, even if they were not keeping the EDPS updated. One key priority is the development of a “research and innovation sandbox,” with the name ODIN: “Operational Data for Innovation.”

The term “sandbox” comes from the world of software development. There, it refers to an isolated technical environment in which software can be developed and tested without having any external effects. As one IT company puts it: “Think of a sandbox as a controlled playground where applications, code, and files can be tested or executed to see how they behave… a digital sandbox allows experimentation and testing without repercussions outside its confined space.”[87]

The AI Act introduces an obligation for national governments to set up “at least one AI regulatory sandbox.” The aim is “to facilitate the development and testing of innovative AI systems under strict regulatory oversight before these systems are placed on the market or otherwise put into service.” Despite its merits, this obligation also externalises the costs of “innovation” by private business onto the public. Access to these sandboxes is to be free, at least for small and medium sizes businesses and start-ups.[88]

Europol’s sandbox is aimed exclusively at the development of AI for law enforcement purposes, whether managed by Europol or by one or more EU member states. To use the wording quoted above, this sandbox would be a digital playground for the police. According to a document from April 2023, the overarching aim is for “value creation at speed”[89] – a term which recalls, at least in part, the Silicon Valley motto of “move fast and break things.”[90]

This apparent need for speed has led Europol to develop a “minimum viable product” version of the sandbox, “so that value creation may begin sooner.”[91] This wording echoes that of the EY and RAND Europe study on the SDSI. This noted that “the EU SDSI could develop from a basic version (Minimum Viable Product) as a short-term solution to an advanced version in the long-term, based on the needs of the Member States.”[92]

The “minimum viable product” approach means developing an environment that can only be accessed by Europol staff, as allowing external access would require stronger security measures and thus imply longer development times and higher costs. Equally, it would not be possible to use personal data in this environment for developing or testing AI tools.[93] This is described as resolving “the need for speed with the need for thoroughness.”

At the same time, the agency plans to develop a separate sandbox that will allow the use of personal data. However, access would still be limited to Europol staff. According to the April 2023 document, in this environment “tool selection and prototyping may already have happened. Now is the time to validate the new capability against a live, operational dataset containing personal data.”[94] If this proves successful, the “capability” may be put into use. The same document states that this sandbox could “become the core of the future EU Security Data Space for Innovation.”

From sandbox to pipeline

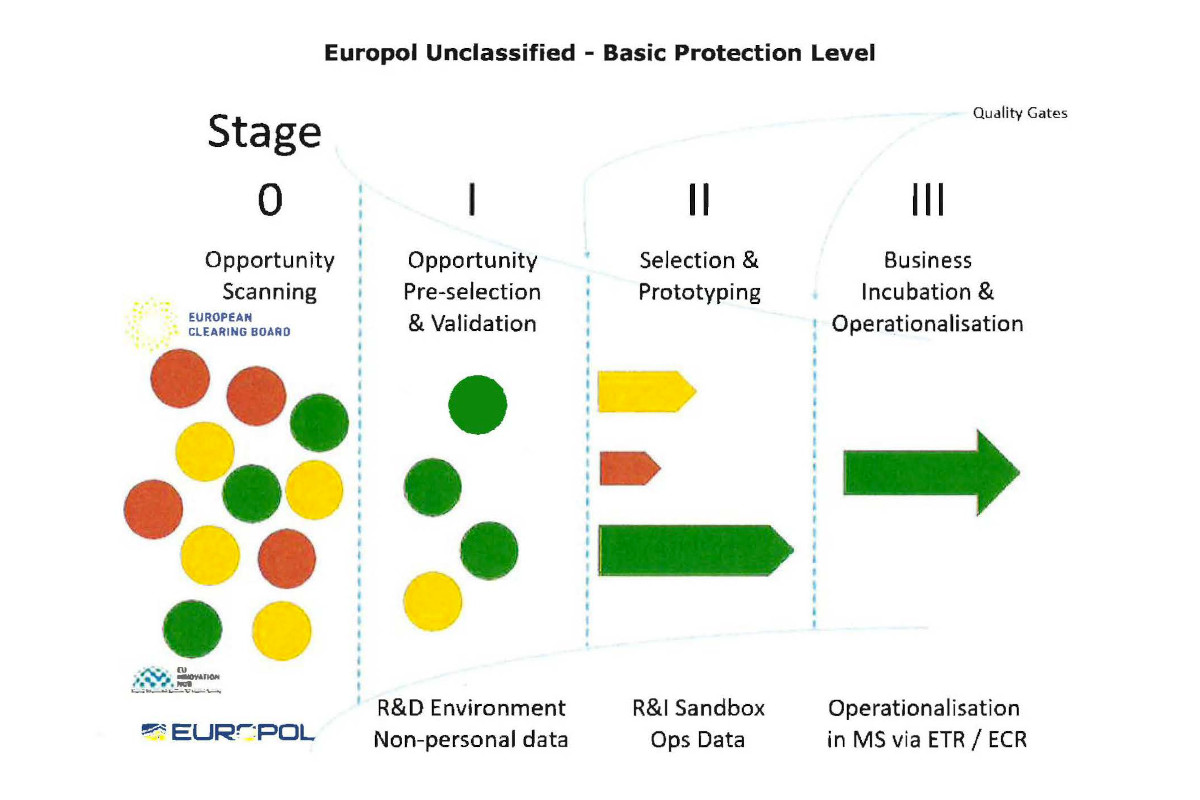

The sandbox is designed as one part of a larger whole, which Europol refers to as a “Research & Innovation Pipeline.” Through this, the agency would play a role in finding, testing, developing and deploying AI, machine learning, and other policing technologies. If a particular technology passes through all the stages, they “may progress to full operationalisation.”

Europol's planned "Research and Innovation Pipeline"[95]

At the first stage, officials working for Europol, the EU Innovation Hub or the European Clearing Board would seek out promising technologies for further development (“opportunity scanning”). These may be “outcomes of the H2020 [security research] projects, or the results of the work of Core Groups or ad hoc collaboration with academic and industry,” a Europol document notes.[96]

The next phase would see “pre-selection and validation” of selected tools or technologies. Those chosen to progress further would be developed and tested within Europol’s “sandbox” using operational data, including personal data. “Technologies that pass through all relevant compliance and security checking of each stage may progress to full operationalisation,” according to the agency.[97]

One way in which technologies that pass through the pipeline may be put to use is through the Europol Tool Repository. This allows Europol and member states to share different tools and technologies via a platform managed by the agency. Europol describes it as “technology sharing as a new form of police collaboration.”[98] As of September 2023, it held 24 tools, had more than 1,500 users, and had seen more than 1,000 downloads of different tools, some of which “have already supported several operations across Europe.”[99]

Europol plans to “further develop the Innovation Pipeline concept” as one of its strategic priorities for the 2024-25 period. This indicates that the pipeline itself is not yet fully-functioning, or even fully planned. The sandbox, meanwhile, is describing as having “paramount strategic significance as it will enable Europol to fulfil its role in leading Law Enforcement Innovation.” It is described as “a precondition and enabler” and an “infrastructural foundation” for “numerous depending initiatives.”[100] This may well include the Security Data Space for Innovation.

< Previous section

3. Security in AI agencies

Next section >

Annex I: High-risk systems under the AI Act

Notes

[1] We have borrowed this term from the Mizue Aizeki, Laura Bingham, and Santiago Narváez: “Infrastructure – digital or material – has real sticking power; that’s the point. Once a highway splits a community in half, a new permanence stifles the din of protest, and people move on. We use the term digital infrastructure to describe the establishment of a foundation that will be fundamental to how world powers will practise migration control; and, as it embeds itself, increasingly beyond challenge – a unified strategic intervention by powerful countries, with the US coveting the vanguard. While it may look like technological experimentation (like AI-powered robot dogs on the border) or one-off opportunistic data-grabs (like networks of international data-sharing agreements), the growth of digital border infrastructure is by design. This is enabled through joined-up digital technologies that settle into the kind of rigid, ‘motiveless’ permanence granted to other infrastructures, like submarine communications cables, protocols and servers that run the internet, an electrical grid or a superhighway.” See: ‘The Everywhere Border: Digital Migration Control Infrastructure in the Americas’, Transnational Institute, 14 February 2023, https://www.tni.org/en/article/the-everywhere-border

[2] Email, 8 February 2025.

[3] A document archive will be published at: https://statewatch.org/securityai

[4] ‘Draft minutes of the 2nd meeting of the Working Group on Artificial Intelligence’, 14 October 2021, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4762/annex-11-minutes_2nd-wgai-meeting-document-8-_redacted.pdf

[5] Deloitte study for European Commission, ‘Opportunities and challenges for the use of artificial intelligence in border control, migration and security . Volume 1, Main report’, 28 May 2020, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/c8823cd1-a152-11ea-9d2d-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

[6] eu-LISA, ‘Roadmap for AI initiatives at eu-LISA’, October 2021, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4756/roadmap-for-ai-initiatives-at-eu-lisa.pdf

[7] Deloitte study for European Commission, ‘Deliverable 3.01: AI Centre of Excellence definition’, HOME/2020/ISFB/FW/VISA/0021, undated, p.3, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4757/deliverable-d3-01_-ai-centre-of-excellence-definition.pdf

[8] eu-LISA, ‘Roadmap for AI initiatives at eu-LISA’, October 2021, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4756/roadmap-for-ai-initiatives-at-eu-lisa.pdf

[9] ‘Deliverable 3.01: AI Centre of Excellence definition’, p.7

[10] ‘Deliverable 3.01: AI Centre of Excellence definition’, p.4

[11] ‘Deliverable 3.01: AI Centre of Excellence definition’, p.4

[12] ‘Deliverable 3.01: AI Centre of Excellence definition’, p.6

[13] Email, 8 February 2025.

[14] Justice and Home Affairs Council, ‘Outcome of the Council meeting’, 14755/19, 2 and 3 December 2019, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/42594/st14755-en19_final.pdf

[15] ‘EU Innovation Hub on Internal Security’, 5757/20, 18 February 2020, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-5757-2020-INIT/en/pdf

[16] Innovation Hub Team, ‘EU Innovation Hub for Internal Security – multi-annual planning of activities 2023-26’, Council doc. 5603/23, LIMITE, 16 February 2023, p.29, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4704/1335957-v1-eu_innovation_hub_for_internal_security_multi-annual_planning_of_activities_2023-2026_st05603_en-public.pdf

[17] Frontex, ‘Frontex publishes technology foresight on biometrics for the future of travel’, 21 October 2022, https://www.frontex.europa.eu/innovation/eu-research/news-and-events/frontex-publishes-technology-foresight-on-biometrics-for-the-future-of-travel-us6C6v

[18] ‘Europe’s techno-borders’, Statewatch/EuroMed Rights, July 2023, pp.36-39, https://www.statewatch.org/media/3964/europe-techno-borders-sw-emr-7-23.pdf

[19] ‘EU Innovation Hub for Internal Security - Work plan 2024’, Council document 7745/24 ADD 1, 27 March 2024, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4763/europol-innovation-hub-report-7745_24_add_1.pdf

[20] EU Innovation Hub for Internal Security, ‘AI cluster workshop – kick-off meeting’, 1 March 2024, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4764/doc-5_edoc-1369040-v2-draft_-_agenda_ai_cluster_-_kick_off_meeting_-_eu_innovation_hub_-_1_march_2024.pdf

[21] EU Innovation Hub for Internal Security, ‘AI cluster workshop – 8-9 April 2024, Europol HQ – Agenda’, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4765/doc-6_edoc-1365887-v5-draft_-_agenda_-_eu_innovation_hub_-_ai_cluster_workshop.pdf

[22] The document archive will be published at: https://statewatch.org/securityai

[23] ‘Beyond debiasing: Regulating AI and its inequalities’, European Digital Rights, https://edri.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/EDRi_Beyond-Debiasing-Report_Online.pdf

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Article 7, Europol Regulation, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02016R0794-20220628#art_7

[27] Europol, ‘Consolidated Annual Activity Report 2020’, p.13, https://www.europol.europa.eu/cms/sites/default/files/documents/consolidated_annual_activity_report_2020_caar.pdf

[28] Innovation Hub Team, ‘EU Innovation Hub for Internal Security – multi-annual planning of activities 2023-26’, Council doc. 5603/23, LIMITE, 16 February 2023, p.21, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4704/1335957-v1-eu_innovation_hub_for_internal_security_multi-annual_planning_of_activities_2023-2026_st05603_en-public.pdf

[29] European Clearing Board - Tools, Methods and Innovations in the field of technical support of operations and investigations, ‘Terms of Reference’, 5 March 2021, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4766/2021-03-05-edoc-1153324-v8-terms-of-reference-eucb.pdf

[30] Europol, ‘Operational Agreements’, undated, https://www.europol.europa.eu/partners-collaboration/agreements/operational-agreements

[31] European Clearing Board, ‘Annex to EuCB Terms of Reference – Management of Core Groups/Strategic Groups’, undated, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4766/2021-03-05-edoc-1153324-v8-terms-of-reference-eucb.pdf

[32] ‘Section 4: Details of the security budgets’ in ‘At what cost? Funding the EU’s security, defence and border policies, 2021-27’, Statewatch/Transnational Institute, April 2022, https://eubudgets.tni.org/section4/#1

[33] ‘Annex to EuCB Terms of Reference’, p.3

[34] ‘Annex to EuCB Terms of Reference’, p.4

[35] Ibid.

[36] Innovation Hub Team, ‘EU Innovation Hub for Internal Security – multi-annual planning of activities 2023-26’, Council doc. 5603/23, LIMITE, 16 February 2023, p.21, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4704/1335957-v1-eu_innovation_hub_for_internal_security_multi-annual_planning_of_activities_2023-2026_st05603_en-public.pdf

[37] European Clearing Board Strategic Group on AI, agenda for meeting on 21 March 2023, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4768/2023-03-21-edoc-1422470-v1-sg-ai-agenda-21-march-2023_redacted.pdf

[38] European Clearing Board Strategic Group on AI, agenda for meeting on 18 September 2024, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4769/2024-09-18-edoc-1422479-v1-sg-ai-agenda-18-september-2024_redacted.pdf

[39] ‘NeoConOpticon: The EU Security-Industrial Complex’, 17 February 2009, https://www.statewatch.org/media/documents/analyses/neoconopticon-report.pdf; ‘Market Forces: the development of the EU security-industrial complex’, August 2017, https://www.statewatch.org/media/documents/analyses/marketforces.pdf

[40] Article 66, Regulation 2019/1896, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32019R1896

[41] Frontex, ‘Frontex to provide border security expertise to European Commission’s research projects’, 6 February 2020, https://www.frontex.europa.eu/media-centre/news/news-release/frontex-to-provide-border-security-expertise-to-european-commission-s-research-projects-ZrCBoM

[42] Article 10(1)(x), Regulation 2019/1896, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32019R1896

[43] Frontex, ‘Horizon projects’, undated, https://www.frontex.europa.eu/innovation/eu-research/horizon-projects/

[44] Frontex, ‘Research grants’, undated, https://www.frontex.europa.eu/innovation/eu-research/research-grants/

[45] Frontex, ‘Budget 2024’, 4 March 2024, https://prd.frontex.europa.eu/document/budget-2024/

[46] ‘Automated Fortress Europe’, AlgorithmWatch, 2024, https://algorithmwatch.org/en/automated-fortress-europe/

[47] Frontex, ‘Border Management and Innovation Centre (BoMIC)’, undated, https://www.frontex.europa.eu/assets/EUresearchprojects/News/Day2/4_BoMIC.pdf

[48] Ibid.

[49] Frontex, ‘Single Programming Document 2024-2026’, 23 January 2024, p.168, https://prd.frontex.europa.eu/document/management-board-decision-8-2024-adopting-the-single-programming-document-2024-2026-including-the-multiannual-programming-2024-2026-the-work-programme-2024-and-the-budget-2024-the-establishment-plan/

[50] Frontex, ‘Single Programming Document 2024-2026’, p.38

[51] Shirin Ghaffary, ‘OpenAI Pitched White House on Massive Data Center Buildout’, Government Technology, 25 September 2024, https://www.govtech.com/artificial-intelligence/openai-pitched-white-house-on-massive-data-center-buildout

[52] Tobias Mann, ‘As AI booms, land near nuclear power plants becomes hot real estate’, The Register, 25 March 2024, https://www.theregister.com/2024/03/25/ai_boom_nuclear/

[53] ‘Advancing United States Leadership in Artificial Intelligence Infrastructure’, Executive Order 14141, Federal Register, 14 January 2025, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/01/17/2025-01395/advancing-united-states-leadership-in-artificial-intelligence-infrastructure

[54] ‘Revitalising Nuclear: The UK Can Power AI and Lead the Clean-Energy Transition’, Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, 2 December 2024, https://institute.global/insights/climate-and-energy/revitalising-nuclear-the-uk-can-power-ai-and-lead-the-clean-energy

[55] European Commission, ‘Artificial Intelligence for Europe’, COM(2018) 237 final, 25 April 2018, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0237

[56] However, it does include a requirement for standards that should aid in reducing “consumption of energy and of other resources” by AI systems (Article 40(2)). The Commission is obliged to report on the implementation of these standards (Article 112(6)).

[57] Claire Fernandez and Katharina Wiese, ‘The mirage of EU techno-solutionism to the climate crisis’, EUobserver, 7 January 2025, https://euobserver.com/Digital/ar125f5e3f

[58] European Commission, ‘The European Commission’s priorities’, 16 July 2019, https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024_en

[59] European Commission, ‘A European strategy for data’, undated, https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/strategy-data

[60] European Commission, ‘Staff Working Document on Common European Data Spaces’, SWD(2022) 45 final, 23 February 2022, p.3, https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/just/redirection/document/83562; European Commission, ‘Data space for security and law enforcement’, https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/opportunities/portal/screen/opportunities/topic-details/digital-2022-cloud-ai-02-sec-law

[61] European Commission, ‘EU Strategy to tackle Organised Crime 2021-2025’, COM(2021) 170 final, 14 April 2021, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0170

[62] European Commission, ‘Staff Working Document on Common European Data Spaces’, SWD(2022) 45 final, 23 February 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/just/redirection/document/83562

[63] Study to support the technical, legal and financial conceptualisation of a European Security Data Space for Innovation, 22 February 2023, p. 2, https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/document/download/4ad85efa-cccf-41ac-a3c7-84d33b5102d7_en

[64] This funds projects on supercomputing, AI, cybersecurity and digital skills.

[65] European Commission, ‘Data space for security and law enforcement’, https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/opportunities/portal/screen/opportunities/topic-details/digital-2022-cloud-ai-02-sec-law

[66] European Commission, ‘Staff Working Document on Common European Data Spaces’, SWD(2024) 21 final, 24 January 2024, p.43, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-5855-2024-INIT/en/pdf

[67] EY and RAND Europe study for European Commission, ‘Study to support the technical, legal and financial conceptualisation of a European Security Data Space for Innovation’, 22 February 2023, https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-02/Data%20spaces%20study_0.pdf

[68] European Commission, ‘Staff Working Document on Common European Data Spaces’, SWD(2024) 21 final, 24 January 2024, p.42, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-5855-2024-INIT/en/pdf

[69] ‘Staff Working Document on Common European Data Spaces’, p.43

[70] European Commission, ‘Call for proposals on data sets for the European Data Space for Innovation’, 21 March 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/opportunities/docs/2021-2027/isf/wp-call/2021-2022/call-fiche_isf-2022-tf1-ag-data_en.pdf

[71] TESSERA, ‘Consortium’, undated, https://tessera-project.eu/consortium-page/

[72] European Commission, ‘Call for proposals on data sets for the European Data Space for Innovation’, 21 March 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/opportunities/docs/2021-2027/isf/wp-call/2021-2022/call-fiche_isf-2022-tf1-ag-data_en.pdf

[73] ‘LAGO’, CORDIS, updated 15 September 2022, https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/101073951

[74] GRACE (https://www.grace-fct.eu), STARLIGHT (https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/101021797), AIDA (https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/883596)

[75] Article 4(4), Europol Regulation, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02016R0794-20220628

[76] Europol, ‘Europol Industry and Research Days: Invitation to present your product’, 10 November 2023, https://www.europol.europa.eu/publications-events/events/europol-industry-and-research-days-invitation-to-present-your-product

[77] Europol, ‘Europol Industry and Research Days 2025’, 3 February 2025, https://www.europol.europa.eu/publications-events/events/europol-industry-and-research-days-2025

[78] Europol, ‘Binding document defining the general scope for the research and innovation projects (application of Article 8 of the Management Board Decision further specifying procedures for the processing of information for the purposes listed in Article 18(2)(e) of the Europol Regulation)’, 23 February 2023, EDOC #1268633v8a

[79] Europol, ‘Programming Document 2024-26’, p.39, https://www.europol.europa.eu/cms/sites/default/files/documents/Europol_Programming_Document_2024-2026.pdf

[80] Europol, ‘Programming Document 2024-26’, p.46

[81] Europol, ‘Binding document defining the general scope for the research and innovation projects (application of Article 8 of the Management Board Decision further specifying procedures for the processing of information for the purposes listed in Article 18(2)(e) of the Europol Regulation)’, 23 February 2023, EDOC #1268633v8a, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4770/europol-binding-document-on-research-and-innovation-projects.pdf

[82] “This work is also linked to the Data Refinery Area concept including, ways to process large volumes of data both structured and unstructured, in a forensically sound environment, data enrichment with OSINT, commercial databases and internal resources, creation and enrichment of ETL pipelines [Extract Transform and Load] including graphical, SQL (Structured Query Language) and relational databases, and data visualization tools including Virtual Reality/Augmented Reality (VR/AR).”

[83] EDPS, ‘Mission report: [censored] exchanges on the implementation of Article 33a Europol Regulation’, undated, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4771/2024-0737_001_redacted.pdf

[84] Letter from Thomas Zerdick, Head of Unit, EDPS Supervision and Enforcement Unit, to Jürgen Ebner, Deputy Executive Director, Governance Directorate, Europol, ‘Request for information regarding the implementation of Article 33a of the Europol Regulation (Research and Innovation)’, 1 October 2024, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4772/2024-0737_002_redacted.pdf

[85] Ibid.

[86] Ibid.

[87] Proofpoint, ‘What Is a Sandbox?’, undated, https://www.proofpoint.com/uk/threat-reference/sandbox

[88] Article 57, AI Act, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32024R1689

[89] Europol, ‘Building the Research and Innovation Pipeline: Update on the implementation of article 33a and the R&I Sandbox environment’, 17 April 2023, EDOC #1301551v2, document for meeting of the Information Management Working Group meeting on 16-17 May 2023, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4774/europol-building-the-research-and-innovation-pipeline.pdf

[90] ‘Did Mark Zuckerberg Say, 'Move Fast And Break Things'?’, Snopes, 29 July 2022, https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/move-fast-break-things-facebook-motto/

[91] ‘Building the Research and Innovation Pipeline: Update on the implementation of article 33a and the R&I Sandbox environment’, p.3, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4774/europol-building-the-research-and-innovation-pipeline.pdf

[92] EY and RAND Europe, ‘Summary of the study in support of the Call for Proposals under the Internal Security Fund on Data Sets for the European Data Space for Innovation’, 20 February 2023, p.3, https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-03/EU%20SDSI%20summary%20document_en.pdf

[93] Europol, ‘Building the Research and Innovation Pipeline: Update on the implementation of article 33a and the R&I Sandbox environment’, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4774/europol-building-the-research-and-innovation-pipeline.pdf

[94] Europol, ‘Building the Research and Innovation Pipeline: Update on the implementation of article 33a and the R&I Sandbox environment’, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4774/europol-building-the-research-and-innovation-pipeline.pdf

[95] Europol, ‘Building the Research and Innovation Pipeline: Update on the implementation of article 33a and the R&I Sandbox environment’, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4774/europol-building-the-research-and-innovation-pipeline.pdf

[96] Europol Innovation Lab, ‘Progress Report and Strategic Priorities 2024-2026’, 22 September 2023, EDOC #1321956v13, p.4, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4775/europol-innovation-lab-progress-report-and-plan-2023-25.pdf

[97] Ibid.

[98] Ibid.

[99] Ibid.

[100] Europol Innovation Lab, ‘Progress Report and Strategic Priorities 2024-2026’, p.5, https://www.statewatch.org/media/4775/europol-innovation-lab-progress-report-and-plan-2023-25.pdf

Our work is only possible with your support.

Become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Previous article

Next article

Spotted an error? If you've spotted a problem with this page, just click once to let us know.