Frontex mandate review 2026: violent border practices to be expanded further

Topic

Country/Region

19 February 2026

The European Border and Coast Guard Agency, better known as Frontex, is set for a major overhaul, with it seeming likely Frontex’s mandate will be expanded by the end of 2026. Along with increased border guard staffing, the agency could see its role in border control and deportations extended far beyond European territory. In this analysis, researcher Marloes Streppel breaks down the main themes of the proposed Frontex overhaul, details the EU’s main motivations and priorities and concludes with concerns raised by civil society groups and academics.

Support our work: become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Image: Frontex

Written and researched by Marloes Streppel.

Under Regulation 2019/1896, the EU's border agency Frontex is due a mandate review in 2026. It is very likely the headcount of Frontex’s uniformed officer force known as the Standing Corps will be increased, but that is only the start. The mandate review is also expected to act as a gateway to expanding Frontex’s role in deportations, including deportations between non-EU countries, as well as Frontex’s role in the controversial ‘return hubs’ system expected to be rolled out in coming years.

Internal discussions between the EU member states and the Commission are also taking place concerning a wider expansion of the agency’s core functions and possible involvement in the EU’s response to ‘hybrid threats’. This includes but is not limited to the alleged instrumentalisation or ‘weaponisation’ of migration at the EU’s borders. Taken together, these plans represent a radical overhaul of the EU border agency’s mandate, pushing its forces and influence far beyond Europe’s borders.

The Background: Frontex history and evolving role

Frontex was founded in 2004 and became operational the following year. There have been multiple revisions to its mandate since then (2007, 2011, 2016, and 2019), with the last decade marking a significant expansion. Frontex’s main responsibility is to implement the EU’s European Integrated Border Management (IMB) framework, which encompasses various tools and methods for controlling the bloc’s external borders. These include actions in third countries to decrease irregular departures towards the EU, agreements and cooperations with third countries neighbouring the EU, border control measures at the external borders, analyses to predict future migration trends and the deportation of undesired migrants out of the EU.

The 2019 Frontex regulation required the Commission to carry out a review of the agency by the end of 2023. This review, carried out by the Commission between May 2022 and October 2023, found “no immediate need for a revision of the EBCG Regulation or its annexes”, though it did highlight certain actions as particularly important for addressing issues within the agency. It recommended:

-

The full implementation of the agency’s new organisational structure (adopted in 2023, and amended in 2025), focussing on the development and implementation of a new chain-of-command structure and improved communication channels, particularly regarding the Standing Corps

-

The development and regular update of Frontex’s ‘capability roadmap’. This document, made in collaboration with member states, offers guidance on developing their own border assets and working more closely with Frontex on the recruitment and training of national staff and the Standing Corps

-

Better strategic oversight and management of deportations by the Frontex management board

-

Improved coordination and communication on deportations between the agency, the European Commission and the new EU Return Coordinator, as well as between the agency and member states.

-

The continued growth of the Standing Corps – Frontex’s uniformed border force – up to 10,000 officers by 2027, with a special focus on getting the Standing Corps’ category 1 frontline border force fully operational.

-

The provision of accurate and up-to-date situational awareness and risk analyses, by further developing the European Border Surveillance System EUROSUR, and the increased use of vulnerability assessment data in risk analyses.

The Commission also set out an Action Plan that laid out a series of recommendations to improve the functioning of the agency.

Context: Frontex under fire for complicity in border abuse

The Commission’s evaluation took place as the agency was under investigation for its alleged involvement in human rights violations, specifically the illegal border practice of summary expulsions or ‘pushbacks’, on the Aegean Sea. Just one month before the review began, Frontex’s director Fabrice Leggeri resigned following a report from the European Anti-Fraud Office1. This report detailed how the agency’s Fundamental Rights Officer (FRO) was denied access to information and reports of serious incidents involving Frontex staff, including witness testimony of specific violations and how Frontex management tolerated a culture of under-reporting among its border guards. It also documented a pattern of Frontex surveillance drones (FSAs) recording pushbacks carried out by the Greek coast guard and then failing to make accurate reports of the events, if any were made at all.

The Commission’s report made no clear mention of these issues. Instead, it concluded that the agency’s fundamental rights framework “effectively contributes to the prevention of fundamental rights violations.”

Frontex’s upcoming revision: Standing Corps, Deportations, and ‘Hybrid Threats’

In July 2024, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen set out the Commission’s political guidelines for 2024-2029. These guidelines called for Frontex to be strengthened, including a further expansion of the Standing Corps, from 10,000 to 30,000, and for the agency to be given more “state-of-the art technology for surveillance and situational awareness”, alongside its own equipment and staff. All of this is intended, in the words of the Commission guidelines, to ensure the agency can “protect our borders in all circumstances.”

Changes of such magnitude require a revision to the 2019 Frontex Regulation. Therefore, the Commission announced in March 2025 – one year following its review of the 2019 Regulation – that it would attempt to update the regulation in the third quarter of 2026.

This upcoming revision is expected to make changes that go well beyond the Standing Corps. Discussions among member states about Frontex’s future show interest in the agency’s future focus on migration control in third countries, and the expansion of the agency’s core functions, well beyond border management and deportations.

The Standing Corps

With regards to the “growing complexity of challenges” at the external border, a Council of the EU note underlines that any growth to the Standing Corps, beyond what is outlined in the 2019 Regulation, must first require a discussion on the agency’s future mandate and operations. Areas that might have “room for improvement” include the rules governing the Standing Corps (including staff regulations and financial provisions) and technical equipment.

Frontex’s role in third countries

According to the Council, many member states believe the “flexibility to conclude more targeted forms of agreements with third countries” could make Frontex a more desirable partner for third countries along key migratory routes. Within this context, the Council note points to the need to discuss the “most effective means of cooperation with international organisations present in third countries.”

Effective is a word often used in the context of measuring the effects of Frontex’s mandate, relations with other organisations and countries and general operations. It sounds professional, clinical, and non-visceral, but “effectiveness” in this context actually describes the ability to restrict the movement of non-EU nationals, both towards the EU and around their own countries and regions.

Member states have also discussed the potential role of Frontex in managing deportations from one third country to another (which is not allowed under the current regulation) and in the management and functioning of so-called ‘return hubs’ – deportation reception and detention facilities – proposed by the Commission in March of 2025 and endorsed by the Council in December.

Frontex’s Core Functions

According to an EU Council note, some member states have questioned whether the 2019 Regulation sufficiently covers Frontex’s role in the upcoming Pact on Migration and Asylum. Others observe that the geopolitical landscape has changed significantly since 2019, implying that Frontex’s role in border control around the EU and further afield should be expanded to keep pace. Accordingly, the Council note invites delegates to discuss what Frontex’s role should be in the future. It asks whether Frontex’s ‘core functions’ - deportations and border management – should be expanded to have the agency take on additional functions beyond Integrated Border Management2 and whether it should be provided with the tools and equipment to help member states respond to ‘hybrid threats’ such as the alleged weaponisation of migration flows.

In reviewing, and perhaps updating, the Frontex Regulation, the Commission aims to address gaps identified in its evaluation, to “prepare and equip Frontex for its increased role as the operational arm of the EU in border management, ensuring a high level of security at the EU’s external borders in response to the new operational challenges” and to further develop the European Integrated Border Management systems.

Concern from Civil Society and Rights Groups

The proposed revision of Frontex’s mandate is set to be published by the Commission in the third quarter of 2026. As it prepares this proposal, the Commission is gathering feedback for an impact assessment, including from member states, civil society and rights groups, policy experts, academics and the public.

The main concerns for the Frontex Regulation, expressed by the Commission in its public Call for Evidence, include:

-

A lack of clarity on some of Frontex’s tasks, making cooperation with third countries and the processing of personal data “not sufficiently flexible” and “complex,” and hindering the agency’s situational awareness, cross-border crime prevention and deportation activities. The current regulation does not, in the Commission’s view, sufficiently define the role of Frontex in combating cross-border crime and includes no role for Frontex in supporting EU visa policy.

-

Limited effectiveness of Frontex in deportations, “including as regards the appropriate representation of return (deportation) authorities in the Agency’s management board, insufficient human and budgetary resources and the fact that return operations are not subject to vulnerability assessment.” Another perceived limitation is Frontex’s lack of a mandate for arranging deportations between third countries.

-

The training of border guards and operational procedures across Member States lacks harmonisation, making cooperation between member states and Frontex less effective.

-

Structural and practical obstacles to effective use of Frontex staff and technicalequipment, including difficulties with recruitment and retention of staff, certain incompatible rules for border guards and procurement and deployment challenges related to technical assets.

-

Adjustment of Frontex’s governance and oversight if the agency is to carry out more functions, regarding the involvement of member states and EU institutions as well as the roles of the Fundamental Rights Officer, Data Protection Officer and other internal control structures.

Criticisms and concerns: Shared Responsibility, Data Protection, and Oversight.

Among the dozens of responses to the call for evidence that have come in from academics, civil society and rights groups and NGOs, as well as businesses and EU citizens, many have pointed out the flawed systems of accountability and transparency that will likely worsen if not properly addressed during this upcoming revision – especially when combined with an expansion of the agency’s current mandates into the controversial areas of deportations between non-EU countries and responses to hybrid threats.

Shared responsibility

Both the 2016 and 2019 Regulations stress the principle of “shared responsibility” over the external borders between Frontex and national authorities, with an emphasis on the fact that “member States retain primary responsibility for the management of their sections of the external borders”. Through the concept of shared responsibility, the EU has established a form of border governance where multiple actors are simultaneously responsible for the same task. In practice, this diffusion of responsibility reinforces a system where Frontex can avoid accountability. This concern was pointed out by both Mariana Gkliati, assistant professor at Tilburg University, and those involved in the Shared Project, a group of various people and entities lobbying for clear and transparent guidelines around the concept of shared responsibility.

Border Externalisation: pushing the EU’s control out around the world

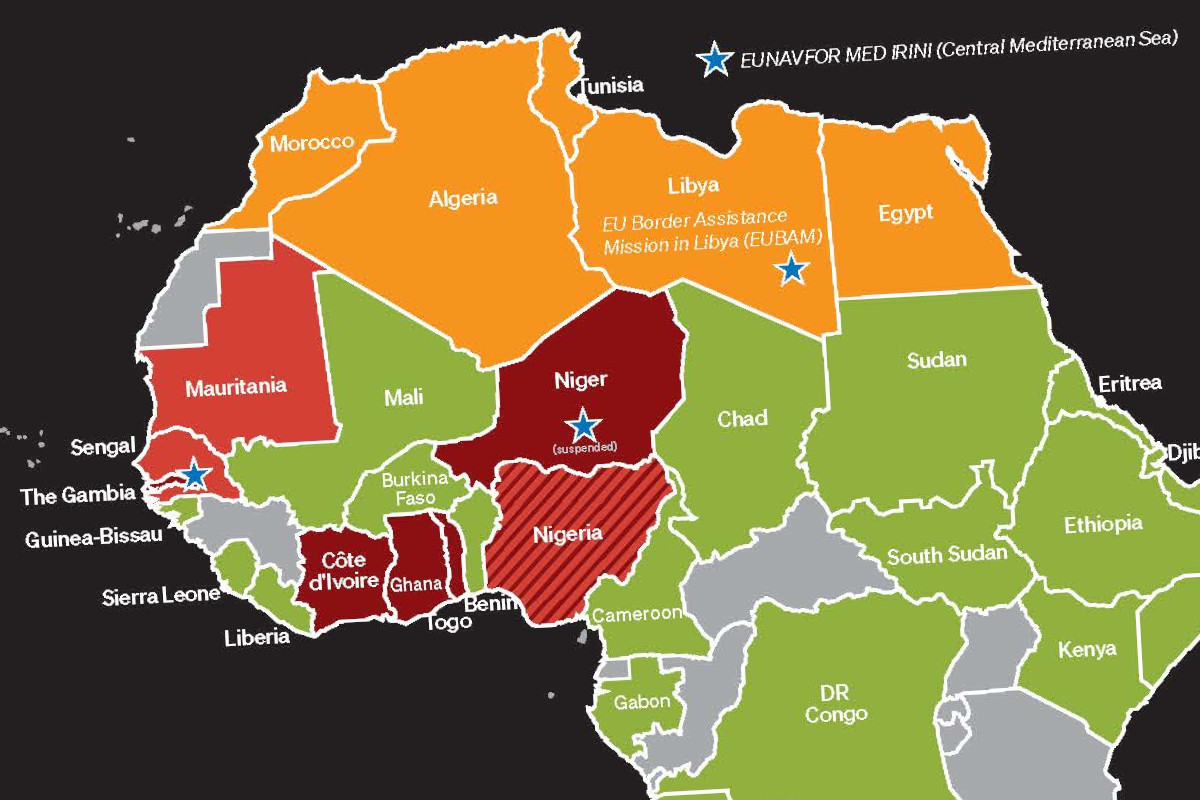

Another concern with the proposed revision to the Frontex Regulation is the agency’s growing cooperation with non-EU countries, as well as the lack of transparency and violations of fundamental rights that cooperation comes along with. Various submissions, including from Statewatch, the Transnational Institute, the Refugee Law Initiative, as well as various academics, focus on the problems associated with the EU’s growing dependence on the outsourcing of border control. These concerns include a lack of transparency and accountability. They also address what many see as the re-emergence of colonial practices restricting the movement of people in Africa, both within their own countries and across whole regions, denying them their right to make their own choices.

Data Protection

Frontex has a very poor reputation with data management and protection. Several NGOs have raised concerns over increasing Frontex’s surveillance powers in this context. The NGO Access Now discussed the risks inherent in weakening Frontex’s Data Protection rules, especially when it comes the already problematic practice of gathering and processing personal data from migrants arriving at semi-formal reception areas known as ‘hotspots’.

Oversight

The NGO I Have Rights has called for civil society to be included in the monitoring system of Frontex. It also expressed a wariness of increasing the competencies of the agency’s existing internal and external oversight bodies, as these run the risk of providing cover for the agency’s illegitimate and rights-violating practices.

Conclusion: expanding the EU's destructive border practices even further

The proposed Frontex overhaul is the product of a system of border management that refuses to take responsibility for the dangerous and deadly borders it creates. Rather than seriously address the systemic faults of the agency’s mandate and operations – faults which allow European border forces to disregard the rights and safety of people trying to reach the EU – the Commission’s proposal reflects yet another instance where perceived ‘threats’ to national and international security are used to justify an ever more restrictive and violent system of border management. It happened in 2016, and again in 2019, and it will happen again now. While the given ‘crisis’ of the moment may change, the story remains the same. Although Frontex’s overhaul is still to come, the stage has already been set and the actors have all memorized their lines.

--

1Leggeri is now an MEP with the far-right French National Rally party.

2 The 2019/1896 Regulation defines Integrated Border Management as: 1. Border control, 2. Search and rescue operations, 3. Risk analysis, 4. Information exchange, 5. Inter-agency cooperation, 6. Cooperation among the relevant Union institutions, bodies, offices and agencies, 7. Cooperation with third countries, 8. Technical and operational measures within the Schengen area related to border control, 9. Return, 10. The use of state-of-the-art technology including large-scale information systems, 11. A quality control mechanism, in particular the Schengen evaluation mechanism, the vulnerability assessment and possible national mechanisms, 12. Solidarity mechanisms, in particular Union funding instruments

Our work is only possible with your support.

Become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Further reading

€2 billion in 15 years: how Frontex finances Fortress Europe

Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, pays out hundreds of millions of euros every year to EU and Schengen member states. The money supports the agency’s standing corps of border guards, operations at the EU’s external borders, and cooperation with non-EU states, amongst other things. Data visualised here shows the scale and scope of the funding provided by Frontex: more than €2 billion between the beginning of 2008 and the end of 2024.

New report examines Frontex's growing role in West Africa

A new report provides a critical examination of the evolving role of Frontex, the EU Border and Coast Guard Agency, in West Africa.

Frontex accused of failing to prevent pushbacks and child rights violations in the Balkans

Frontex’s own fundamental rights watchdog has raised the alarm over pushbacks and serious protection failures in countries where the agency operates.

Spotted an error? If you've spotted a problem with this page, just click once to let us know.