Moving borders with history: new ways of thinking about border externalisation

Topic

Country/Region

19 August 2025

Europe is doubling down on its outsourcing of border controls to other states, particularly in Africa - and new ways of thinking about border externalisation are needed to generate effective responses. A recent academic article, summarised here, argues that postcolonial and decolonial analysis can help generate those responses.

Support our work: become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Image: NASA Johnson, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Introduction

The relaxation of the internal borders of the Schengen area in the early 1990s was paralleled by a hardening of external frontiers. This included the increasing deployment of extra-territorial migration control practices, in “partnership” with neighbouring countries.

Sugarcoated in cooperation agreements and vague concepts such as the “whole-of-route approach”, the EU’s border has been driven southwards by a proliferation of security-oriented measures. These include deportation agreements, joint border patrolling and capacity building, typically accompanied by the increasing use of development aid to stop migration…

…Or so goes the widely accepted narrative of EU border externalisation, deployed in both European policy circles and more critical fields of research. However, a recent article by Sebastian Cobarrubias and Martin Lemberg-Pedersen argues that this story is only the tip of the proverbial border externalisation iceberg.

This article summarises Cobarrubias and Lemberg-Pedersen's arguments. Neglecting what remains submerged in the waters of history risks, at best, constraining our understanding of this border practice. At worst, it may perpetuate racialised narratives that cast migrants as threats to the Western status quo.

Space and time: Challenging border externalisation research to think historically

Cobarrubias and Lemberg-Pedersen’s article [1] is the introduction to a special issue of the journal Geoforum. The issue examines border externalisation in the EU-West African region through a postcolonial and decolonial lens. The article summarised here is an analytical synthesis of the other articles within the issue.

The authors critique common framings of border externalisation as being overly spatial and focused on contemporary dynamics, obscuring the longer imperial histories underpinning these practices. They advocate for re-historicisation and the de-centring of Eurocentric understandings, by situating current trends within the enduring legacies of colonial encounters.

In referring to decolonial and postcolonial approaches, Cobarrubias and Lemberg-Pedersen engage with two distinct theoretical traditions, both of which offer a powerful critique of the continuing research and policy influence of colonial imbalances and Eurocentrism. They argue that these approaches bring a much-needed temporal depth to analyses of border externalisation.

The authors contend that post- and decolonial analysis shows how the EU’s extra-territorial border practices is an "upcycling" of colonial logics. By this, they emphasise a “re-adapting (of) something into a new product, giving its components a second life through re-use.” Thus, we can trace commonalities between colonial dynamics and contemporary practices, while nevertheless recognising that they are not a direct continuation.

In understandings of border externalisation, the authors underline that this upcycling is primarily reflected in:

- the way border outsourcing reproduces racialised power imbalances forged in the colonial period; and

- in how old imperial ways of seeing the world continue to inflect the EU’s engagement with “transit” or third countries.

Reviewing the various contributions to the series, the authors identify several important consequences of this analytical approach for future critical engagement with EU border externalisation practices.

Been there, done that: Reminding EUrope of its colonial precedents

Firstly, they argue that postcolonial and decolonial perspectives help to counter claims about the innovative and unprecedented nature of the EU’s extraterritorial border control practices. Typically, research and commentary on border externalisation—often motivated by efforts to understand contemporary developments occurring alongside Europe's growing political and institutional integration—has tended to frame it as a new phase in European management of migration and borders.

However, a postcolonial or decolonial approach casts the chronological net further back in time to expose border externalisation as nothing new. Rather, it builds upon a long history of connections, networks and relationships that until very recently were understood as part of imperial spaces. While colonial-era practices of migration management were not conceptualised as “border externalisation”, they very much involved a similar projection of European priorities into African territory.

This dynamic was particularly visible in the former UK government’s proposal to send asylum seekers for processing in Rwanda which, far from being a shocking innovation, drew on a number of colonial precursors.

For instance, during WWII, the British government transferred some 2,700 Greek refugees from colonial Egypt to camps in Rwanda, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This measure itself emerged from within a much longer tradition of sending “problematic” groups elsewhere – for example, the rise of convict colonies, the transportation of poor British children across the empire in the 1880s and 1930s, and a plethora of programmes relocating refugees to European imperial possessions throughout the 20th century.

This re-historicisation provides an important challenge to Europe’s “colonial amnesia”. Particularly since the end of the Cold War, the EU and its proponents have asserted the Union as a novel political project grounded in human rights and the rule of law, distinct from the continent’s legacies of colonialism.

Post- and decolonial analysis of border externalisation challenges this assertion, revealing how EU border policy has always been—and continues to be—entangled with its imperial past. This shines a revealing light on European attempts to discard centuries-long histories of racism, enslavement, dispossession and genocide.

Moreover, such an approach highlights how externalisation practices are not just about borders moving through space, but also unstable in time. Without a sense of history, it is easy to take European national borders for granted, as something fixed. Yet, post- and decolonial analysis demonstrates that they have always been much less certain, at times stretching across empires in ever-shifting ways.

Applied to border externalisation, we can see the role extraterritorial migration management has played—and continues to play—in defining and redefining European and African borders most often along lines of racial and socioeconomic inequality.

Europe is not the centre of everything

At the same time, the authors emphasise that decolonial and postcolonial methods facilitates an important de-centrering of Europe in studies of border externalisation. Much research on the practice today – often influenced by policy priorities – takes on state- and Eurocentric perspectives that privilege the role of the EU and member states in driving policy exchanges as seemingly one-way affairs in the face of African passivity.

This can be seen in research that, for example, limits its scope to policy debates in European capitals or engages with EU-African agreements without considering political dynamics in African states. Even in efforts to scrutinise colonial legacies of migration management, there remains the risk of re-centering Europe in our analysis—this time as the dominant colonial actor of the past—and presenting today’s outsourcing of border controls as a simple continuation of the colonial era.

Post- and decolonial critiques, however, encourage us to look beyond the metropole-colony binary and consider the role of independent local dynamics in shaping border policy and its consequences.

By adopting what the authors call “a non-eurocentric postcolonial gaze”, European perspectives, policies and histories become one among many. Looking beyond relations with Europe, post- and decolonial approaches bring into focus a variety of local and regional histories that play an equally important role in influencing how extraterritorial border policy is put into practice.

As one contribution to the special issue demonstrates, this is evident in the way the Nigerien government and communities draw on their own historically-specific understandings of migration and mobility, that often conflict with European and international approaches to migration management. The negotiations between these differing perspectives actively shape how border externalisation is implemented, resulting in outcomes that go far beyond policy plans devised in Brussels.

De-centering Europe in this way has a number of valuable consequences for those working on outsourced EU border policy. Firstly, it demands an understanding of policy transfer that accounts for the complexity of reality – EU border externalisation does not occur within a vacuum but is carried out across regions, countries and communities that have their own histories and political climates.

Consequently, generalised migration management concepts – such as externalisation, forced migration and displacement – are only useful when we understand what they mean within local realities and political dynamics, as much as in EU policy circles.

But more than this, European critics of border externalisation are encouraged to share the spotlight with a broader range of people who are impacted by and seek to challenge extra-territorial migration management in their own ways, beyond the EU-Africa relationship. This opens up exciting possibilities for broader and more inclusive transnational research and advocacy efforts that oppose violent EU border practices.

Race against time: Considering racialisation in border externalisation

The authors additionally highlight how post- and decolonial approaches bring to light the ways in which border externalisation intersects with processes of racialisation. Colonial projects operated through clearly defined racial hierarchies that designated who had the right to move and where. These dynamics persist today through national border policies that exclude racialised “outsiders” like the illegal migrant or the failed asylum seeker.

Accordingly, through a post- and decolonial lens, we are able to trace how national and EU attempts to shift border management beyond national boundaries are inevitably influenced by these historically rooted racial anxieties. At the same time, they create and reinforce current forms of racial discrimination both within former coloniser and formerly colonised states.

A telling example of this is the connection of European border policy to a wave of attacks on black Africans—primarily migrants—in Tunisia, stirred up by Tunisian president Kais Saied. This violence feeds off long-standing racist anxieties with roots in Ottoman imperialism and the North African slave trade which cultivated Arab-Black, slaver-slave binaries that were then reinscribed by French colonial racial hierarchies. Today, outsourced border measures encourage Tunisia to “control its borders” against sub-Saharan and primarily Black African migration, giving new life to this long history of anti-Black racism in North Africa.

Attention to this intersection with racialisation paves the way for a more transnational and interdisciplinary research scope. It brings migration studies into conversation with wider fields of inquiry such as critical race theory. Meanwhile, it broadens the language of critique for those challenging Europe’s violent extraterritorial border practices. Framing outsourced migration control as a global racial justice issue can connect it to migrant justice movements in Europe or efforts to address anti-Black racism in North Africa.

Consider the bigger picture: Border externalisation beyond migration management dynamics

Another benefit of post- and decolonial perspectives underlined by the authors is that they help frame border externalisation as part of wider geopolitical interests. In other words, EU migration management, especially when it involves an outsourcing of power beyond borders, is never solely about controlling movement. It is also always tied up with broader political and economic programmes of influence, which equally have their own histories entwined with imperialism.

This illuminates, for instance, how border externalisation is deployed as a tool for reworking diplomatic relations by EU and partner nations alike. This was the case when Turkey leveraged its strategic role in the EU border control apparatus to pressure Brussels in favour of Turkish interests. Extreme public debt in countries like Libya and Senegal – also a colonial hangover and postcolonial source of Western dominance – offers another example. Outsourced migration management is often packaged in or with financial and development aid, fostering increased dependence on Europe and a strengthened western sphere of influence at the expense of migrants’ lives.

For those working on EU border externalisation policy, this angle allows us to make important connections with wider historical power imbalances and processes. It can bring up important questions about historical and present-day extractivism, or the enmeshment of migration control with development aid and trade priorities. This allows critics of border externalisation to engage with broader programmes of international justice, such as efforts to decolonise international debt or the fight for a just transition, while strengthening challenges to EU and international foreign policy.

Conclusion

Overall, Cobarrubias and Lemberg-Pedersen underscore how postcolonial and decolonial analyses of EU border practices encourage us to think beyond contemporary policy framings. They highlight the need to join the dots between border outsourcing and a range of other issues: local political and historical dynamics; the continued and complex realities of racialisation; and the machinations of wider geopolitical interests.

Fundamentally, they facilitate an interrogation of the ways in which a plethora of assumptions from the colonial period continue to influence European border externalisation policies today: assumptions about who holds power, how people are ranked in terms of skin colour or country of birth, and who is permitted to move and where. With the EU set to continue and expand its border externalisation priorities in the years to come, our analytical toolkit also needs to grow, in order to develop effective responses.

Author: Samuel Allan

Note

[1] ‘Beyond Presentism in Border Externalization Studies: Upcycled Spatio-Cultural Geographies of Imperial Times’, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016718524002586

Our work is only possible with your support.

Become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Further reading

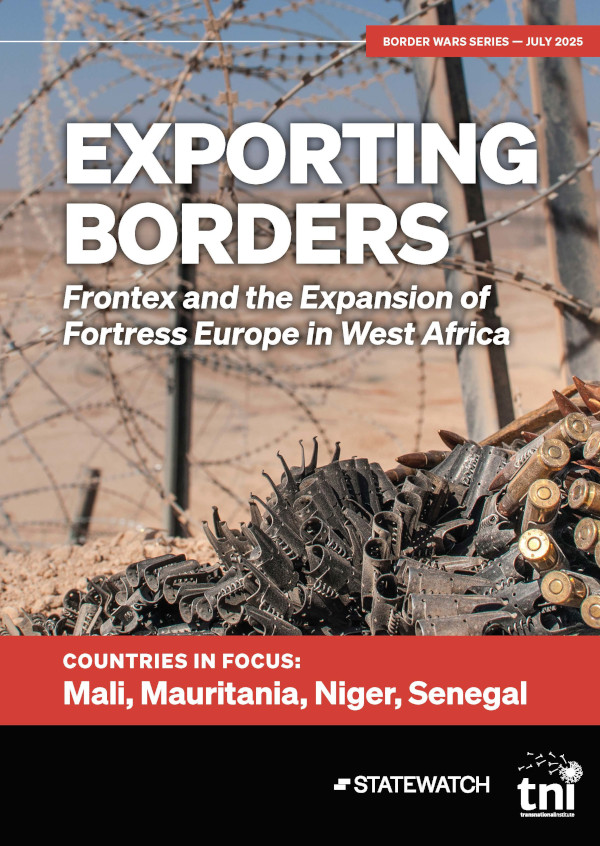

Exporting Borders: Frontex and the Expansion of Fortress Europe in West Africa

The EU is pushing its migration control far beyond Europe’s borders. This report, co-published with the Transnational Institute, exposes how Frontex operates in West Africa under the cover of cooperation, entrenching neo-colonial influence, undermining rights, and reshaping the Sahel into a securitised buffer zone.

EU states demand more migration control cash in next long-term budget

EU member states want significantly more money allocated to migration control in the bloc’s next long-term budget, set to run from 2028 to 2034. This is according to a document produced by the Polish EU Council Presidency and circulated on 12 June. Spending on external migration control from current budgets is already above expectations.

New report examines Algeria's role in the European border regime

A new report looks at the way the Algerian government has increased its involvement in border control initiatives promoted by European governments, after decades of reluctance to do so.

Previous article

Will the EU finally stop financing Israel’s genocide in Gaza?

Next article

€2 billion in 15 years: how Frontex finances Fortress Europe

Spotted an error? If you've spotted a problem with this page, just click once to let us know.