Behind closed doors: Europol’s opaque relations with tech companies

Topic

Country/Region

30 October 2025

As part of its research into the expanding—and largely unchecked—use of AI by EU security agencies, Statewatch delves into largely uncharted territory: Europol’s links with the private sector. A survey of this landscape reveals conflicts of interests, secrecy and opacity, and a whole array of intrusive and invasive technologies that Europol would like to adopt, and make more widely available to European police forces.

Support our work: become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

A special report by investigative journalist Giacomo Zandonini, supported by European Digital Rights.

Key points

- Europol, the EU policing agency, is working hard to expand its cooperation with industry – to the extent that Microsoft employees now have desks in the agency’s HQ in The Hague

- The agency has an interest in robotics; open-source intelligence; forensic analysis systems; software that can process vast audio, text and video datasets; and more

- The agency has for years cooperated with, and even relied on, private companies – including many that are deeply implicated in Israel’s surveillance of and control over Palestinians

- While private companies are invited to showcase their wares, requests to Europol for information from journalists and independent organisations are often blocked in the name of commercial secrecy or data protection

- This includes refusing to release details on how and why a former Europol official was able to take up employment with a private company working with the policing agency, seemingly as soon as he left his role

- With the European Commission aiming to double the agency’s size, the potential for revolving doors and conflicts of interest will only grow

Europol to industry: “send information directly”

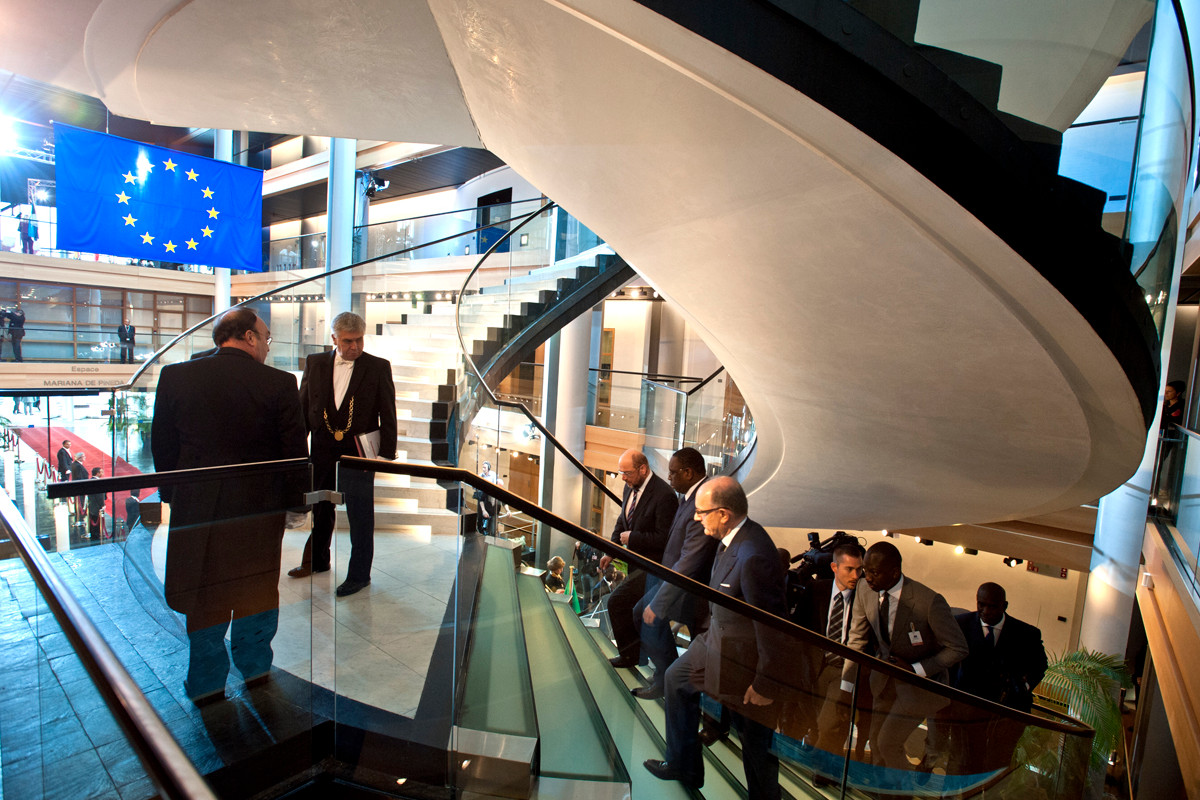

Image: Andrew Hart, CC BY-SA 2.0

The InCyber Forum is one of Europe’s top cybersecurity events. This year, it was held in Lille, France. Paul-Alexandre Gillot, the Europol official leading the agency’s Joint Cybercrime Action Taskforce, was there. He issued a strikingly direct call to private firms: “send information directly.”

Gillot urged companies to channel cyber intelligence straight to Europol through its newly launched Cyber Intelligence Gateway—a tool meant to tighten coordination between law enforcement and industry. “We need information—do not hesitate,” he said, underscoring both the escalating urgency of cyber threats and Europol’s pivot toward more assertive intelligence-gathering.

The appeal is grounded in Europol’s expanded mandate, in effect since June 2022. The agency’s latest reform aims to ease data sharing with both public and private entities, enable the processing of large-scale datasets, and advance research through the use—and development—of AI-driven crime-fighting tools.

Rarely subjected to close scrutiny, Europol’s ties with the private sector stretch back nearly as far as the agency’s 26-year history. The 2012 launch of the European Cybercrime Centre, and the 2020 launch of the Financial and Economic Crime Centre and the Innovation Lab, have all significantly deepened that cooperation.

This article examines a recently established platform central to Europol’s growing collaboration with private companies: Research and Industry Days, during which dozens of tech groups showcase their AI-based solutions to the agency. Similar events are hosted by Europol’s counterpart agencies dealing with border control (Frontex) and IT systems (eu-LISA).

Documents obtained through transparency requests, open-source material and interviews shed new light on Europol’s technological ambitions, the private actors promoting intrusive data extraction and analysis tools, and the limited oversight surrounding these relationships. Together, these factors open the door to potential conflicts of interest and privacy risks.

A long alliance, hidden from view

Image: Valsts Policija, CC By-NC-ND 2.0

Europol’s partnership with the internet and security industries has expanded alongside its evolution into a pan-European criminal intelligence hub. Tasked with supporting national law enforcement across the EU, the agency now analyses massive data flows, mines its rapidly growing archives for personal information, and facilitates cooperation on cross-border investigations.

The agency’s ties with private industry are set to deepen even further. A proposal to “enhance police cooperation and reinforce Europol’s role in combating migrant smuggling and human trafficking” has just been approved by EU legislators. Proposals for more substantial reform, aiming to “turn Europol into a truly operational police agency and double its staff,” are due to be published in 2026.

For now it is the 2022 reform that largely governs Europol’s activities. Despite Paul-Alexandre Gillot’s open call to “send information,” the exchange of personal data between Europol and private companies remains controlled by formal procedures and agreements. It’s a system that makes it formally impossible for any individual or group to directly upload information into Europol’s vast databases.

Instead, data must be routed through national government “contact units” in EU member states—or third countries granted adequacy status, currently limited to the United Kingdom and New Zealand. The rules only allow direct reception or transmission of personal on a case-by-case basis. Authorisation from Europol’s executive director is also required—and reserved for emergencies or serious, immediate threat to the bloc’s security, such as terrorism or child sexual abuse.

On certains conditions, Europol can make its infrastructure available for data exchanges between member states and private parties. Europol’s access to that data limited to that which is “necessary and proportionate for the purpose of enabling Europol to identify the national contact point” in charge of receiving and passing over the data.

Despite these safeguards on receiving data from private partners, there is little transparency around how Europol approaches these companies, engages them in operational or analytical projects, contracts their services, or licenses their technologies.

Europol’s Financial Regulation, adopted in 2019, states that the agency can stipulate “service-level agreements” with private parties, “without having recourse to a public procurement procedure”. The agency’s annual list of contracts, published every June, specifies that “publication of certain information on contract award may be withheld where its release would impede law enforcement, or otherwise be contrary to the public interest, would harm the legitimate commercial interests of economic operators or might prejudice fair competition between them.”

The 2024 contract list includes for example dozens of entries, most tied to Europol’s routine operations in The Hague—from cleaning services and staff training to security, legal consultancy, IT workstations, and cloud services. Buried within the data are traces of a massive €112 million framework contract for IT services, awarded in 2023—likely the agency’s largest to date—hinting at the scale of its growing digital infrastructure.

Old partners, obscure contracts

Traces of Europol’s engagement with the private sector have surfaced through journalistic investigations, parliamentary inquiries, and the agency’s own communications. Yet Europol has kept its use of certain systems—particularly those most likely to trigger data protection concerns—largely out of public view.

For years, Europol’s expanding data-gathering capabilities relied on Gotham, one of the flagship data-crunching platforms of US company Palantir. This detail emerged from a 2020 journalistic investigation, which uncovered that a lucrative 2012 contract for a “new Europol Analysis System” awarded to French consultancy Capgemini had, behind the scenes, brought Palantir’s now-infamous data fusion and analysis software into the agency’s core operations.

Gotham leverages AI to sift through massive volumes of personal data—ranging from phone records and social media posts to images and profile metadata—identifying patterns and mapping networks of individuals in mere seconds. It forms the backbone of many of Palantir’s predictive policing and surveillance tools, whose deployment by Israeli police and military in Gaza and the West Bank has been extensively documented since 2024.

Europol’s relationship with the US-based company, which is deeply embedded in Washington’s military and intelligence apparatus, has been fraught and marked by opacity. The agency claimed it terminated its Gotham license in 2021. Yet when journalists sought transparency, Europol released just 2 out of 69 documents related to its dealings with Palantir. One of the few disclosed records revealed that the agency had even considered legal action against the company.

From Palantir to Clearview

Peter Thiel, co-founder of Palantir and investor in Clearview AI, in 2014. Image: The DEMO Conference, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Peter Thiel, co-founder of Palantir and investor in Clearview AI, in 2014. Image: The DEMO Conference, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Palantir co-founder and PayPal initiator Peter Thiel has also invested in another US firm widely criticised for its dystopian approach to surveillance: Clearview AI. The company built its tools on a database of billions of facial images and other sensitive personal data scraped from the internet without consent. In recent years, data protection authorities in Canada and Europe have fined Clearview AI and banned the use of its technology within their jurisdictions.

The European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) is responsible for monitoring Europol’s compliance with EU data protection law. After Clearview AI showcased its products at Europol’s headquarters in 2020, during an internal meeting of a taskforce on child sexual abuse material, the EDPS stepped in to offer its views on the company’s software.

The watchdog explicitly recommended that Europol “not engage the services of Clearview AI, as this would likely infringe the Europol Regulation.” Europol was further advised to “not promote the use of Clearview AI at Europol events, or provide Europol data to be processed by third parties using Clearview at these events.”

At the time, a similar automated facial recognition tool—Griffeye Analyze DI Pro—had already been in use at Europol for several years. Its deployment was revealed in 2020 by former MEP Patrick Breyer, then a member of the Joint Parliamentary Scrutiny Group on Europol.

Software developed by the Swedish company Griffeye was used by both Europol’s Cybercrime Centre—in its efforts to combat child sexual abuse—and the agency’s European Counter Terrorism Centre. The tools were delivered under a framework contract with Safer Society Group, then Griffeye’s parent company, which held an agreement with Europol from 2016 to 2020.

Replying to a question posed by Breyer, Europol specified it had used the tools' facial detection capabilities only “in specific cases at the request of member states law enforcement agencies.”

A public-private platform: Europol’s Research and Industry Days

Image: Rory Hyde, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

In 2024, Europol became the latest major EU security agency to launch a dedicated platform for engagement with the private sector: Research and Industry Days. The move followed a broader trend. Frontex had initiated its own Industry Days after its 2016 mandate expansion, which opened the door to research and innovation activities. That same year, eu-LISA—the agency managing the EU’s gigantic migration and justice databases—launched its Industry Roundtables to foster similar partnerships.

Spearheaded by Europol’s tech hub, the Innovation Lab, the first edition of the event was held in January 2024. Companies were invited to pitch a range of surveillance and investigative technologies. These included open source intelligence (OSINT) tools for digital investigations and dark web monitoring, online patrolling systems, robotics equipment, and AI solutions capable of processing and analysing audio, text, video, and vast datasets.

In response to an initial information request from Statewatch, Europol withheld the names of most companies that participated in the event and refused to release their presentations. It later provided an agenda listing 19 entities. Participants ranged from global security giants like France’s Idemia to smaller but well-established firms from the US, Israel, and Europe, as well as two research centres.

The smallest player in the room was the Austrian startup AML Crowd Sentinel. According to materials submitted for the Industry Days, the company was still “in the process of establishing a legal entity to pursue the project” at the time of the event. Notably, its CEO, Dieters Petracs, is a former Europol financial crime official who left the agency in 2016.

Among the tools showcased at the first of the Research and Industry Days were:

- a robotics system with advanced biochemical analysis capabilities, developed by U.S. firm 908 Devices, already supplied to Romanian customs and Ukrainian security forces;

- an augmented reality drone control interface from Finnish company Anarky Labs, currently licensed to Frontex; and

- the “Voice Inspector,” a Czech-made tool marketed as capable of identifying individuals from just three seconds of speech, with claimed voice-matching accuracy across all languages.

Several companies pitched tools for image analysis, mapping individuals’ social networks, predictive modelling and automated decision-making. Among them were Japanese corporation NEC, a global leader in facial recognition technology; and Polish firm Datawalk, which markets its data intelligence platforms as alternatives to Palantir’s Gotham and Foundry. Datawalk has recently secured ties with multiple US and EU security and intelligence agencies, signaling a growing footprint in the surveillance market.

At the time of Europol’s event, NEC’s ties to Europol had already moved into formal contracting. Following a market assessment—whose details were not disclosed—the agency procured NEC’s NeoFace Watch, a machine learning–based facial recognition system, likely in 2023. The EDPS instructed Europol to limit its use to a pilot phase and flagged a series of accuracy concerns, particularly the software’s reliability in identifying children under the age of 12.

There were at least two more companies who presented at the event and whose names were not included in Europol’s official agenda: Prevency and Volto Labs.

The first is a Germany-based company, chaired by Lars Niggemann, that develops OSINT tools and “preparedness” simulators—virtual, interactive reconstructions of real-world scenarios, primarily used in military and security contexts.

At Europol’s event, Prevency presented training in collaboration with ESG Elektroniksystem- und Logistik, a company recently acquired by German defence giant Hensoldt, which has long supplied equipment to the Israeli military. The training focused on “synthetic internet” technology—a simulated digital environment used for security applications and to train algorithms.

Dutch company Volto Labs showcased its Cyber Agent Technology—an AI-powered surveillance platform designed to automatically capture private, secret, and closed-group chats. This apparently includes disappearing messages, attachments, reactions, avatars, and shared files across various social media and messaging apps.

The technology originated from software developed within the Hague Security Delta, a Dutch government-backed tech hub partnered with Europol. Canadian mobile phone hacking firm Magnet Forensics later acquired the software, securing a foothold in The Hague in the process.

Robots, deepfakes, and drones: the 2025 edition

Jürgen Ebner at the 2025 Research and Industry Days. Image: Europol

In February 2025, representatives from at least 32 private technology firms and research projects quietly converged at Europol’s headquarters in The Hague, to present their latest surveillance and data-analysis tools to hundreds of law enforcement officials. The second edition of Europol’s industry event called for innovative solutions in unmanned systems, deepfake detection, OSINT, forensic analysis, financial intelligence and cybersecurity.

This time, the list of companies involved was made public. It included firms whose technologies have been linked to risks for data protection and fundamental rights, such as Spanish company Bee The Data, which develops AI-driven face and behaviour recognition systems. According to the Justice, Equity & Technology Project, its tools are central to the so-called Kuppel System—an AI surveillance platform used by Catalonia’s police force, the Mossos d’Esquadra, to track the behavior of individuals, drones, and vehicles across Barcelona.

Paliscope, a Swedish company with roots in the Safer Society Group—the same umbrella behind surveillance firms Griffeye and NetClean—has drawn criticism for incorporating technology developed by the controversial Polish firm PimEyes. The integration has expanded Paliscope’s facial recognition capabilities by tapping into PimEyes’ low-cost reverse image and video search engine. This allows users to upload photos and scan a database reportedly containing around one billion faces.

Researchers Johanna Fink and Mark Bovermann have described PimEyes as illegal under German law, and data protection authorities in both the UK and Germany have opened inquiries into its use. Under the EU’s Artificial Intelligence Act, systems like PimEyes and Clearview AI are set to be banned starting 2025, unless national security exemptions are invoked.

Some of the companies attending the Industry Days were no strangers to Europol. Czech firm Eyedea Recognition, for instance, has a history with the agency. A 2016 press release from the French defense group Thales—then integrating Eyedea’s vehicle recognition system into its own products—listed Europol as one of the company’s clients.

Asked in 2016 how the partnership began, Eyedea’s chief engineer, Radek Svoboda, said Europol had “met us at a professional conference, tested our product for several months, and then decided to purchase a license.” More recently, in 2023, Czech privacy watchdog Iuridicum Remedium flagged Eyedea’s facial recognition tool, Eyedentity, as potentially posing “high risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons.”

Romanian cybersecurity firm Bitdefender has played a supporting role in major Europol-facilitated operations targeting dark web markets and malware networks, including Operation Endgame in 2025. The company also sits on one of four advisory groups tied to Europol’s European Cybercrime Centre—a forum where the agency engages with private companies and research bodies. In total, these groups bring together around a hundred industry leaders, regularly meeting online, or at Europol’s premises.

Unmanned systems were prominently featured at the event, with companies like Airhub, Roboverse Reply, Boston Dynamics, and Redrone showcasing their latest technologies. Redrone, notably, is owned by US firm Axon—the maker of the TASER. While Axon has long marketed its electroshock weapons as a means to reduce police killings, publicly available data tells a different story, with thousands of deaths linked to TASER use casting doubt on the company’s claims.

Born out of a research project at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and heavily funded by the US Department of Defense, Boston Dynamics has grown into a global provider of robots for military and law enforcement—despite asking clients not to arm its machines.

The company has recently shifted its attention to Europe. In 2023 it opened its first regional office in Frankfurt, near the European headquarters of its parent company, Hyundai. LinkedIn posts reveal that its appearance at Europol’s Industry and Research Days was facilitated by the Innovation Lab of the North Rhine-Westphalia Police in Germany—the first police force in the country to deploy robotic dogs.

Since 2020, Boston Dynamics has partnered with Israeli drone maker Percepto, combining aerial and ground surveillance technologies. Their integrated systems have reportedly been used to monitor Israeli settlements and industrial sites in the occupied West Bank—considered illegal under international law.

Spot, Boston Dynamics’ high-tech robotic dog, has been deployed by law enforcement agencies across the US, sparking concern among civil society groups and lawmakers. Its use by the New York City Police Department was suspended in 2022 following public backlash.

After a pilot deployment in the Bronx, Democratic Representative Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez criticized the program, arguing the robot was being “tested on low-income communities of color with under-resourced schools,” rather than directing public funds toward education and social services.

Secrecy and mobile phone data extraction

Image: Kārlis Dambrāns, CC BY 2.0

Image: Kārlis Dambrāns, CC BY 2.0

A closer examination of Europol’s shady links to Israeli tech giant Cellebrite—one of the companies featured at the 2025 Research and Industry Days—highlights some of the agency’s ongoing challenges with transparency and accountability.

Cellebrite is a global leader in mobile forensics; its flagship tool, the Universal Forensic Extraction Device (UFED), can unlock and extract data from nearly any smartphone by exploiting software vulnerabilities. The device has been widely deployed by police and security agencies around the world, including in Europe, often with little public oversight and under shaky legal bases.

Following a request for access to documents concerning Europol’s ties with Cellebrite from 2023 onward, the agency declined to release any correspondence. It cited the need to protect “commercially sensitive, strictly confidential information as well as intellectual property, including trade secrets,” along with “sensitive information about Europol’s operational capabilities, environments and networks, notably in the field of digital forensic support.”

A heavily redacted, AI-generated pitch presentation for the 2025 Industry Days names three Cellebrite products—Inseyets, Guardian, and Pathfinder—and highlights their ability to deliver what the company calls “magic.” Earlier records show that Europol was invited to the first Dutch edition of Cellebrite’s closed-door “C2C” (Case to Closure) event, held in Schiphol in October 2024, where existing and potential clients gather.

According to Europol’s own disclosures, the agency operated two Cellebrite workstations as early as 2012. The UFED tool appears in connection with two anti–migrant smuggling operations supported by Europol—one in Bulgaria in 2016, the other in Poland in 2019. These cases underscore how digital extraction tools have increasingly become part of border enforcement strategies.

Cellebrite’s positioning in the migration control arena has expanded significantly in recent years. Speaking at the 2019 Border Security Congress—a forum where public agencies and private contractors meet—a senior Cellebrite representative encouraged authorities to extract data from asylum seekers’ phones to reconstruct their journey and “identify suspicious activity prior to arrival.”

The approach includes accessing stored content, browsing history, and social media activity. Over the past decade, several EU member states have adopted legislation allowing authorities to seize or request access to migrants’ phones shortly after arrival.

Cellebrite: deployment against journalists, activists and minority communities

A Cellebrite stand an Italian trade expo in 2012. Image: FPA S.r.l., CC BY-NC 2.0

Despite growing interest in Europe, Cellebrite’s most significant migration control client is undoubtedly US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). The agency’s recent deportation raids—amplified in Donald Trump’s second term as president—are only the most visible sign of its rapid expansion.

According to US government spending platforms, since 2019, ICE has spent over $35.5 million on UFED licenses, with the contract renewed in early 2025. In 2020, following a protracted legal battle, the Electronic Privacy Information Center obtained a cache of internal ICE documents through a lawsuit settlement. These records outlined the capabilities of Cellebrite’s tools to extract data from mobile devices and raised legal concerns over warrantless searches, a clear breach of US constitutional safeguards.

Over the past decade, Cellebrite’s standing has steadily risen among law enforcement agencies—even as its credibility has eroded just as rapidly in the eyes of civil liberties and human rights groups. Its UFED tool has been repeatedly implicated in the surveillance and criminalisation of journalists, activists, and minority communities.

Between 2017 and 2018, Myanmar’s military junta used UFED to extract data from the phones of two Reuters journalists who had exposed atrocities against the Rohingya population. In Honduras, police forces deployed the tool against environmental defenders, while in Hong Kong, authorities used it to unlock the phones of thousands of pro-democracy protesters. Governments in Russia, Bangladesh, Bahrain, Venezuela, and Belarus have also employed UFED to monitor media workers and civil society groups.

In February 2025, Cellebrite announced it had suspended sales to Serbian authorities, following Amnesty International’s 2024 disclosure that its technology was being used to surveil local activists and journalists. In March 2024, activists protesting a deportation flight from Italy discovered their seized phones had been hacked using Cellebrite tools. In March 2023, the Italian police renewed several contracts and licenses with Cellebrite, committing €3.4 million over a three-year period.

The company’s European sales operations are currently led by Alon Zilkha, an Italy-based executive who assumed the role in April 2025, according to publicly available information. Before taking this position, Zilkha oversaw sales at NSO Group, the Israeli surveillance firm behind Pegasus spyware—widely condemned for its involvement in global espionage targeting journalists, activists, and political figures. NSO Group was blacklisted by the US and later fined $168 million for breaching WhatsApp’s privacy protections.

In a 2021 filing to the US Securities and Exchange Commission, Cellebrite admitted that “our solutions may be used by customers in a way that is, or that is perceived to be, incompatible with human rights.” They added that “all users are required to confirm, before activation, that they will only use the system for lawful uses.” Cellebrite, however, “cannot verify that this undertaking is accurate.”

A Cellebrite spokesperson told Statewatch that “adherence to the rule of law, as well as privacy and compliance standards, is a fundamental element of all our partner relationships.” The company added that this commitment is “underscored by the fact we have a publicly declared Ethics & Integrity Committee, which is comprised of many external industry specialists.”

The backgrounds of the seven members of its Ethics & Integrity Committee suggest close ties to the security and military establishments of the US and Israel. Doron Herman, a former “reporter for the Israel Defense Forces,” has shared violent military propaganda on his personal social media accounts—including an image of children’s games in Gaza with the caption “they will never be used again.” He has also repeatedly targeted UN agencies on X, responding to a call by UN Secretary-General António Guterres to end hostilities in Gaza with the comment: “You are a joke!”

Another member, Israeli philosophy scholar Moshe Halbertal, co-authored the Israel Defense Forces’ Code of ethics and reportedly downplayed civilian deaths in Gaza during Israel’s 2014 military operations as “sporadic” mistakes. These remarks stand in sharp contrast to findings by the UN and multiple human rights organisations, which documented deliberate attacks on civilians, including hundreds of children.

When asked about its relationship with Europol, Cellebrite declined to provide details, stating: “As a business practice, we do not share information about specific partner relationships, products, or disclose confidential information regarding contracts and license agreements. To do so would potentially put investigations, police operations, and lives at risk.”

Confidentiality claims and revolving doors

Image: Jen Gallardo, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

One of Cellebrite’s main competitors, Magnet Forensics, also participated in the Research and Industry Days. The Canadian firm develops AI-powered tools for phone extraction, data analysis, and decryption, and has secured lucrative contracts with ICE and other law enforcement agencies. The company has not responded to Statewatch’s repeated requests for comment.

Statewatch asked Europol about its connections from 2020 onwards with some of the companies that took part in the 2025 Research and Industry Days—namely Magnet Forensics, Cellebrite, Eyedea Recognition, Paliscope and its partner PimEyes. The agency replied:

At Europol we use a number of products from various companies. However, we cannot disclose any information about forensic, data analysis or any other tool used for criminal operations. The disclosure of email communications with companies, list of actual licences, product details etc will jeopardise Europol’s operational capabilities, disclose details about operational environments and networks and will breach agreements between companies and Europol.

Law enforcement operations no doubt require a degree of secrecy. However, Europol’s response suggests a broader aversion to transparency—one that appears to go beyond the standards and practices observed by most national police agencies in Europe and the United States.

Sarah Tas, a professor in European law at Maastricht University, told Statewatch that the law governing Europol gives it “the discretion to refuse or redact access to documents, although there may be a clear public interest in having these information available to the public, notably to ensure accountability. This is even more true when this information is related to tools that may have significant consequences on individuals.”

“It is essential for EU agencies to have less discretion in deciding on whether to grant access to documents or not, and there is a significant need for stronger proactive transparency," she emphasised.

When asked about its knowledge of Europol’s contracting and procurement processes, the European Commission told Statewatch that it did not hold information on Europol’s decision not to disclose the names of companies it contracted. It also said that the assessment of what information to include in the agency’s annual list of contracts “remains fully under Europol’s responsibility.”

Asked to comment on Europol’s reply to our press question on relations with private actors, the Commission merely referred to the EU legislation that governs access to documents.

Concerns over conflicts of interest

Image: Digitale Freiheit, CC BY-SA 2.0

This confidentiality does little to assuage concerns about conflicts of interest. A 2023 media investigation raised concerns about close links between the US-based company Thorn, the European Commission, and Europol in relation to a proposed law on combating the spread of child sexual abuse material. This is commonly referred to as the CSAM Regulation, or “chat control”.

Thorn’s intensive lobbying efforts within the EU signalled its ambition to position itself as a central technology provider. This would give it the possibility of securing a role in the bloc’s emerging infrastructure for detecting CSAM, where its AI tools could be used to scan private communications and categorise images. Two former Europol officials working on the same topics had begun to work for Thorn in the same time period. Reacting to the journalists’ revelations, the European Ombudsman opened an inquiry into the move.

In a decision published in February 2025, the Ombudsman found that “the intended post-service activity [of one of Europol’s former officials] raised risks of a conflict of interest, which Europol should have handled as such — that is, by imposing adequate mitigation measures to protect the Agency’s integrity and reputation.”

The Ombudsman concluded that Europol’s handling of the case amounted to maladministration, and urged the agency to review its screening procedures to prevent similar shortcomings. Europol failed to comply with a six-month deadline to report back on the matter. On 15 September, however, it said:

…in 2024 and 2025 Europol has taken measures to enhance the process for handling post-Europol authorisation requests... In particular, for staff leaving the Agency, the process since Q3 2025 includes, in line with guidance by the European Ombudsman, a specific assessment to determine, if relevant, distinct mitigation measures for staff regarding the remaining time in service at Europol when leaving the Agency.

These do not appear to be isolated cases: at least one other instance of a former Europol official transitioning into the private sector has been identified by Statewatch. In April 2023, Sergio Enrique Leal Rodriguez left Europol’s Cybercrime Centre after a decade in post. According to his LinkedIn profile, he immediately joined Maltego Technologies, a private firm specialising in data analysis and investigation tools.

Just months after his departure, Leal Rodriguez returned to Europol’s headquarters in The Hague, this time as an external presenter at an expert meeting of the agency’s unit focused on combating child sexual abuse material, known as Analysis Project Twins. His presentation explored ways to “enhance CSAM investigations using ontologies and standardisation.”

Later that year, in October 2023, he served as a trainer for Europol’s COSEC (Combating Online Sexual Exploitation of Children) course held in Germany—a role he continued in the 2024 edition, aimed at law enforcement officials across Europe. At the 2024 session, he introduced two core components of Maltego Technologies’ platform: Evidence and Monitor.

These tools claim to harness AI to extract and analyse vast volumes of data in real time, primarily from social media, making it “actionable” and capable of “uncovering hidden connections.” The company also had a slot during the open-source intelligence (OSINT) session at the February 2025 Research and Industry Days.

Asked by Statewatch how its procedures for dealing with the employment of former officials were used in the case of Leal Rodriguez, Europol said it “applies a robust process for the request of authorisation of (former) Europol staff members with regard to post-Europol occupational activities.”

Data protection requirements, it added, made it impossible for the agency to comment on individual proceedings. “As you have previously shown an interest in data protection, we trust that you will also respect the personal privacy of the former Europol employee in this matter,” wrote Europol.

Leal Rodriguez, contacted via Maltego Technologies’ press office, did not reply to a request for comment.

Corporate desks at Europol’s headquarters

Bradford L. Smith (President and Chief Legal Officer, Microsoft) and Catherine De Bolle (Executive Director, Europol) at the World Economic Forum in 2019. Image: World Economic Forum, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Bradford L. Smith (President and Chief Legal Officer, Microsoft) and Catherine De Bolle (Executive Director, Europol) at the World Economic Forum in 2019. Image: World Economic Forum, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

While Europol has adopted stricter policies to mitigate conflicts of interest, its collaboration with private industry is poised to expand. This mirrors the agency’s growing size and mandate. In June 2025, Microsoft announced a new partnership with the agency. This will embed corporate representatives at the European Cybercrime Centre to “support joint operations and intelligence sharing to help identify and dismantle the infrastructure used by cybercriminals targeting European institutions and communities.”

Amy Hogan-Burney, Microsoft’s Vice President, described the initiative as the company’s “first operational deployment under our new European Security Program.” The tech giant’s newly established office inside Europol’s headquarters marks the first tangible step of the Cyber Intelligence Extension Programme (CIEP), a recently launched initiative designed to deepen cooperation between Europol and the private sector.

Europol has stated that additional companies will join the programme “in due time,” noting that it is grounded in the agency’s revised 2022 rules governing relations with private entities.

Another indication of Europol’s growing appetite for advanced tech solutions is the Cyber Innovation Forum, a platform launched in 2024 to “bring together leading experts from law enforcement, private industry, and academia.”

The 2025 edition was held in The Hague in mid-November. Europol invited participants to pitch “innovative developments that may have an impact on preventing and combating the different forms of cybercrime (cyber-enabled crime, cyber-dependent crime, child sexual exploitation) leveraging the use of new technologies.”

Although the event is not intended as a showcase for commercial products, its stated areas of interest include artificial intelligence (machine learning, automation, robotics, tool development and testing), “intelligent assistants and smart policing,” as well as unmanned aerial vehicles, biometrics, and ethical hacking.

Expanding the agency, expanding the role of the private sector

Image: Europol

As of 2025, Europol has a workforce of over 1,700 officials (including internal staff, national experts, and consultants) and a €241 million annual budget. The European Commission plans to double the agency’s size, which would significantly deepen the agency’s ties with private industry.

In early 2025, EU member states’ police chiefs endorsed parts of the proposals, emphasizing that “Europol could serve as a vital gateway for obtaining information from private entities, such as online service providers, financial institutions, and cryptocurrency exchanges.” They also called for substantial investment in the agency’s artificial intelligence and data analysis capabilities, intended to support law enforcement bodies across the EU.

Against this backdrop, the lack of transparency surrounding Europol’s procurement processes, contracting practices, and industrial partnerships raises pressing questions about oversight and accountability.

The call for the third edition of the Research and Industry Days, scheduled for late February 2026, only underscores these problems. It invites companies to pitch tools capable of analyzing massive datasets, enabling “real-time social media monitoring,” and developing “integrated AI-robotics platforms with advanced decision-making capabilities.”

It also warns participants that:

…any documents produced may be subject to public access requests… However, given that these events focus specifically on addressing law enforcement needs rather than public dissemination, selected participants retain full control over their materials and may decline sharing their presentations or provide modified versions suitable for public release. Similarly, participants may opt to exclude their names (individual or company) from any publicly communicated agenda or documentation.

This is not quite what the law says. Where an EU institution or agency holds documents produced by a third party and a request is filed for those documents, the agency should consult with that third party to see if any exceptions to transparency are applicable – “unless it is clear that the document shall or shall not be disclosed.” Europol appears to be offering companies a pre-emptive guarantee against releasing information: hardly cause for optimism in the struggle against public-private policing secrecy.

Our work is only possible with your support.

Become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Further reading

EU police chiefs seek limits to “ambitious overhaul” of Europol

Another upgrade to the powers of EU police agency Europol is in the works. The European Commission wants to see an “ambitious overhaul” so it can become “truly operational.” European police chiefs, however, are sceptical. A “strategic debate” amongst member state delegations is ongoing, but remains behind closed doors.

Activist demands compensation from Europol for illegal surveillance

A Dutch political activist last week filed a legal complaint with EU police agency Europol, seeking compensation for the unlawful processing and handling of his personal data. The move is likely to lead to litigation at the European Court of Justice to determine Europol’s liability. This case could help clarify the rights of individuals seeking redress against Europol’s growing surveillance and data-gathering efforts.

EU’s secretive “security AI” plans need critical, democratic scrutiny, says new report

The EU is secretively paving the way for police, border and criminal justice agencies to develop and use experimental “artificial intelligence” (AI) technologies, posing risks for human rights, civil liberties, transparency and accountability, says a report published today by Statewatch.

Spotted an error? If you've spotted a problem with this page, just click once to let us know.