Parliamentary lawyers: democratic oversight needed for EU-Tunisia migration agreement

Topic

Country/Region

15 March 2024

Last July, the EU and Tunisia signed a memorandum of understanding in which the EU promised substantial support for Tunisian migration and border controls. An opinion by the European Parliament Legal Service, obtained by Statewatch, concludes that although the agreement is not legally binding, some form of parliamentary oversight is required. Currently, that is not the case, but MEPs are demanding it – in particular due to the authoritarian nature of many of the regimes the EU is supporting.

Support our work: become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

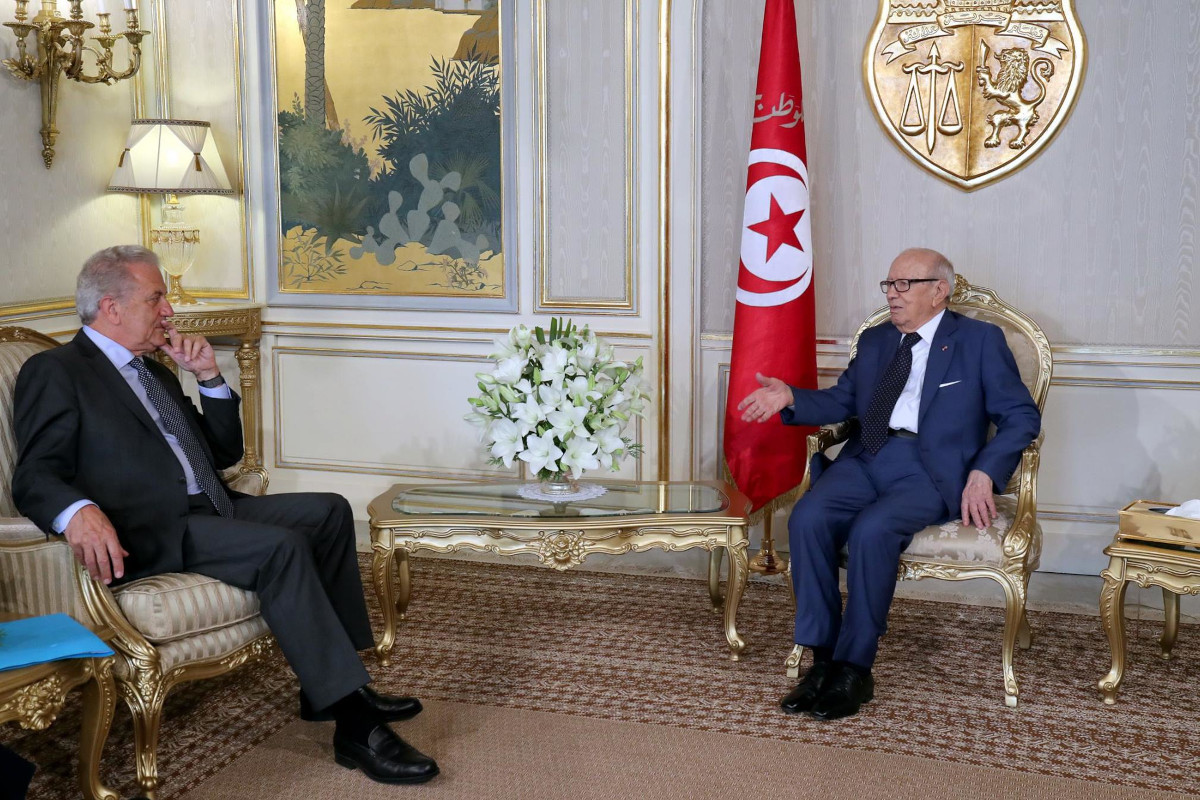

Image: European Union, CC BY 4.0 DEED

This article is published in partnership with Migration-Control.info.

EU-Tunisia agreement: “bankrolling dictators”

The opinion, drafted by the European Parliament (EP) Legal Service in December last year, analyses the July 2023 “Memorandum of Understanding [MoU] on a strategic and global partnership” between the EU and Tunisia, which was published as a “press statement.”

It is being published here after the European Parliament on Wednesday approved a resolution that condemned the Commission’s provision of €150 million to Tunisia through an urgent written procedure, sidestepping normal forms of scrutiny.

Early last year the Tunisian president Kais Said gave a speech that drew on the “great replacement” conspiracy theory normally espoused by the European far-right, ushering in a wave of attacks and arrests against sub-Saharan African people. The EP resolution refers to “an authoritarian reversal and an alarming backslide on democracy, human rights and the rule of law,” noting that “over the last year, President Kais Saied has had opposition politicians, judges, media workers and civil society activists arbitrarily arrested and detained.”

Following the parliamentary vote , the Commission was accused of “bankrolling dictators” by the French MEP Mounir Satouri, part of the Greens/EFA group.

Externalisation continued

The MoU covers economic and trade issues such as agriculture and the “digital transition,” and includes a substantial section on “migration and mobility.” This includes commitments to dealing with “the root causes of irregular migration,” as well as “combating irregular migration” and “developing legal pathways for migration.”

It says the EU will “endeavour to provide sufficient additional financial support, in particular for the provision of equipment, training and technical support necessary to further improve the management of Tunisia’s borders.” The text and underscores that Tunisia “is not a country of settlement for irregular migrants,” and that the North African country “control[s] its own borders only.”

A separate EU document published today by Statewatch shows that despite Tunisia’s claims to “control its own borders only,” the support promised by the MoU comes with European interests at the forefront.

Legal opinion

Following the signing of the MoU, the EP’s civil liberties and foreign affairs committees requested an opinion from parliamentary lawyers to provide advice on:

“…the legal status, mandate and institutional accountability of “Team Europe”, the normal procedures and their application in this case in relation to concluding agreements and committing the EU budget, including the role of the Council and especially of the Parliament.”

The opinion concludes that the MoU is not an international agreement with legally binding effects and cannot be used as a basis for financial commitments from the EU towards Tunisia, but that it should nevertheless be subjected to some form of parliamentary oversight, for which there is a treaty basis.

No binding effects

The EU’s founding treaties set out the procedure for concluding international agreements, including agreements that have important financial implications.

The Legal Service opinion concludes that, given the terms of the MoU, their context and the object and purpose of the text, it cannot be considered an international agreement insofar as it has no binding legal effects.

This means that the MoU is unable to provide a basis for EU financial commitments. In particular, it does not refer to specific financial contributions to be made by the EU to Tunisia – which, as noted above, already come to at least €150 million – but only to future possibilities of committing the EU budget.

Moreover, the MoU, like the Joint Declaration of June 2023 that preceded it, appears to be “limited to making a policy statement about possible next steps on the basis of Union action already decided by the competent institutions of the European Union,” say the parliament’s lawyers.

Budget commitments

In the Legal Service’s view, the financial aspects of the MoU require further measures to commit to EU funds, namely implementing acts from the European Commission.

In other words, any references to EU financial assistance do not modify ongoing cooperation between the EU and Tunisia. To commit funds to the country, the EU institutions must follow the procedures laid down in the different EU funding instruments for each of the policy areas mentioned in the MoU, such as economic stability, development, trade, energy – and, of course, migration.

The European Parliament’s Legal Service expects that most of the Commission’s implementation measures would be based on the Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI) – ”the main financial tool for EU international cooperation from 2021 to 2027.”

The opinion stresses that the signature of the MoU with Tunisia was not required “to be able to commit the EU budget,” indicating that it is a statement of political will and intention above anything else.

“Team Europe” has no legal status

The European delegation that visited Tunisia to sign the MoU was made up of European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen, Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni and Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte, with the Commission declaring that they were acting in “a Team Europe spirit.”

“Team Europe consists of the European Union, EU Member States — including their implementing agencies and public development banks — as well as the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD),” says the Commission.

“This ‘Team Europe approach’ means joining forces so that our joint external action becomes more than the sum of its parts,” the Commission goes on to say. It is unclear what a “Team Europe spirit” implies, as the EU-Tunisia MoU is not included in the more than 150 existing Team Europe Initiatives – but in any case, the EP’s Legal Service says it has no formal legal status.

Parliamentary oversight

The EU treaties do not envisage specific rules for concluding non-binding agreements, but the Court of Justice has ruled that the Commission must obtain the Council’s approval before signing a non-binding agreement with a non-EU country on behalf of the Union.

This procedure is also laid down in an inter-institutional arrangement between the Commission and the Council, which was introduced following the Court of Justice’s judgment.

The European Parliament Legal Service argues that it is unclear whether the Commission sought the Council’s prior authorisation before signing the EU-Tunisia MoU. It has been argued that a failure to do so would be an infringement of the principle of distribution of powers set out in the treaties.

When non-binding agreements with non-EU countries are concluded, the European Parliament is not involved in the negotiations, and the Court of Justice has not yet ruled on the Parliament’s rights or role in this context.

The Legal Service believes that, even when agreements are not binding under international law, “the right to involvement of the European Parliament, as part of the fundamental “democratic principles” of the Union… applies generally to the whole field of external relations” (emphasis in original).

The parliament’s lawyers argue that this would be consistent with the treaty requirement that the Parliament exercise powers of political control over the EU’s external relations.

As things stand, the EU’s only elected institution is being barred from conducting in-depth scrutiny of the growing number of migration control agreements with non-EU states, and more are on the way – a “partnership” with Mauritania was signed last week, and a deal with Egypt is in the sights of the Commission and the member states.

Documentation

- European Parliament Legal Service, Legal status of the Memorandum of Understanding signed in Tunis on 16 July 2023, SJ-0839/23, D(2023)36736, AN/DM/cd, 19 December 2023 (pdf)

Our work is only possible with your support.

Become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Further reading

“Action file” on Tunisia outlines EU’s externalisation plans

An “action file” obtained by Statewatch lays out the objectives and activities of the EU’s cooperation on migration with Tunisia – whose government was heavily criticized by the European Parliament this week for “an authoritarian reversal and an alarming backslide on democracy, human rights and the rule of law.”

Access denied: Secrecy and the externalisation of EU migration control

For at least three decades, the EU and its Member States have engaged in a process of “externalisation” – a policy agenda by which the EU seeks to prevent migrants and refugees setting foot on EU territory by externalising (that is, outsourcing) border controls to non-EU states. The EU’s New Pact on Migration and Asylum, published in September 2020, proposed a raft of measures seeking to step up operational cooperation and collaboration in order to further this agenda.

Joint Statement: Tunisia is neither a safe country of origin nor a place of safety for those rescued at sea

We, the undersigned organisations, issue this statement to remind once again that Tunisia is neither a safe country of origin nor a safe third country. Therefore, it cannot be considered as a place of safety for people rescued at sea.

Spotted an error? If you've spotted a problem with this page, just click once to let us know.