EU/Greece/Turkey: Crisis not averted: security policies cannot solve a humanitarian problem, now or in the long-term

Topic

Country/Region

30 March 2020

At the end of February, the Turkish government announced it would allow refugees to travel onwards to Greece and Bulgaria, in the hope of extracting from the EU further financial support as well as backing for its military operations in Syria. It has now taken up its role as Europe’s border guard again, but the manufactured crisis induced by the Turkish decision and the EU response highlight the long-term failings of the EU’s asylum and migration model.

Support our work: become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Background

On Thursday 27 February, the Turkish government announced that it would allow refugees to cross the border into Greece and Bulgaria, a move that led to shocking violence from the Greek and Bulgarian governments against those attempting to make the crossing and a wholesale abandonment of EU and international refugee law – with the full backing of EU institutions and other member states.

The Turkish government’s decision essentially ripped up the March 2016 EU-Turkey deal, through which Turkey agreed to prevent such crossings in exchange for €6 billion in funds from the EU. Those funds were to be disbursed to projects providing support to refugees in Turkey between 2016 and 2019.

With the time limit up, negotiations between senior European and Turkish officials on maintaining the deal had been taking place in Berlin behind tightly-closed doors, according to a Deutsche Welle report from early February.[1] The European side was apparently concerned that, with a steady increase in the number of people arriving in Greece, the Turkish government was failing to uphold its end of the bargain.

UNHCR figures show that, by land and sea, over 177,000 people arrived in 2016, with 441 people recorded as dead or missing. The EU-Turkey deal was signed in March of 2016. The following year, the number of arrivals fell to 36,310 (59 people were reported as dead or missing). Then the number of arrivals began to creep up again: over 50,000 in 2018 (with 174 dead or missing) and almost 75,000 in 2019 (70 reported dead or missing).[2]

However, if Turkey has failed to keep its side of this Faustian bargain, so have the EU and its member states. The €6 billion committed by the Europeans was to be paid in two halves – €3 billion in 2016 and 2017 (with one-third from the EU budget and two-thirds from the member states), and €3 billion in 2018 and 2019, with the proportions reversed. The Guardian reported on 28 February that the EU “has so far disbursed €3.2bn of the funds dedicated to supporting aid for the refugees and migrants living in Turkey,”[3] just over half the total promised by the end of 2019.

According to the Commission’s most recent monitoring report on the implementation of the ‘Facility for Refugees in Turkey’,[4] which was published in April 2019, the EU provided the €1 billion promised for the 2016-17 period, while the member states were €80 million short of their €2 billion total. They provided that €80 million in 2018, along with an initial €68 million of the €1 billion owed during the 2018-19 period. The report states that the remaining payments from the member states are “planned for 2019-23”. In 2018, the EU paid €550 million of its €2 billion total for the 2018-19 period, with the balance due in 2019. It is unknown if that has been paid, but the member states have clearly been writing cheques that their treasuries won’t cash. With over four million refugees in Turkey, it is unsurprising that the authorities there are not happy with a failure by the EU member states to keep their side of the bargain.

Further complaints on the Turkish side include a failure by the EU to keep its promise on visa liberalisation for Turkish nationals, while numerous reports suggest that hostility towards Syrians living in Turkey has been on the increase for some time[5] – a factor that may not only drive Syrians to want to head for Europe, but one which would also put pressure on the Turkish government to do something to limit the number of Syrians living in Turkey.

At the same time as European and Turkish officials were negotiating in Berlin, events in in the Syrian war were leading to a new exodus of refugees hoping to escape to some degree of safety in Turkey. By the end of February up to a million displaced people were cornered in Idlib, where Russia and Turkey have currently agreed a ceasefire.[6] On 27 February – the same day that the Turkish authorities decided to allow people to head to Europe – the border with Syria was also reportedly opened for 72 hours to allow people to escape the ongoing conflict.[7]

The logic here would appear to be that if more people are allowed in, some have to be allowed out. With some notable, but small, exceptions, the EU appears almost entirely unwilling to welcome any of those people – with disastrous results primarily for refugees, but also for whatever remains of the moral, legal and political credibility of the EU as a symbol of humanitarianism and human rights.

Arrivals in Greece and reactions on the ground

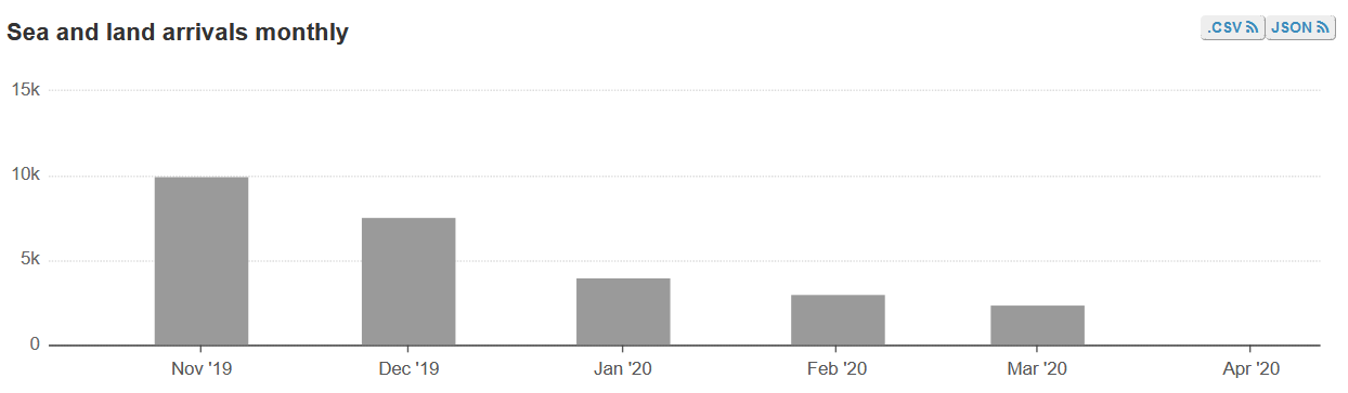

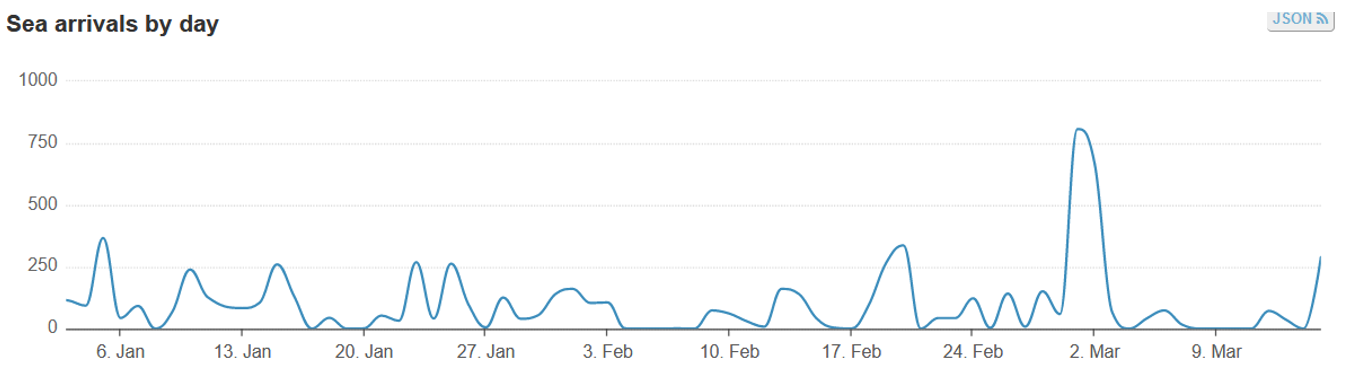

While there was a spike in arrivals caused by the Turkish government’s decision, the total number of people arriving in Greece had been declining for a number of months (as the charts below show) – although the numbers for February and March would certainly be higher had the Greek government not eschewed its obligations to people seeking international protection (ABC News cited the Greek authorities as saying that they had “thwarted 36,649 attempts to enter Greece and made 252 arrests,” between 28 February and 5 March[8]). Nevertheless, the dramatic nature of Erdogan’s announcement and the swift increase in new people travelling to the Greek islands in particular, led to an already-catastrophic situation tipping into outright threats, intimidation and violence against refugees and volunteers seeking to assist them.

Figure 1: Land and sea arrivals in Greece by month. Source: UNHCR, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean/location/5179

Figure 2: Sea arrivals by day on the Greek islands. Source: UNCHR, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean/location/5179

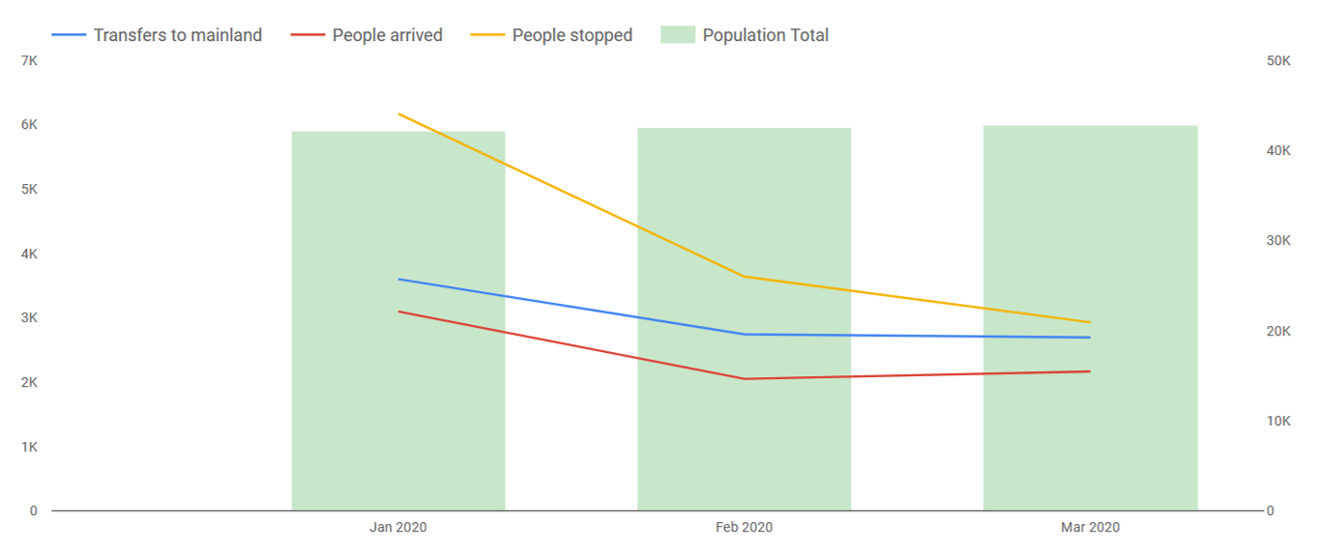

Figure 3: Arrivals by sea on the Greek islands by month. Source: Aegean Boat Report, https://aegeanboatreport.com

Figure 3: Arrivals by sea on the Greek islands by month. Source: Aegean Boat Report, https://aegeanboatreport.com

The Greek islands were in a dire situation before Turkey’s decision. A report for Are You Syrious? highlighted how the July 2019 arrival in government of the conservative Nea Dimokratia (New Democracy, ND) party had already led to a significant decline in living conditions and social stability:

“…the severity of the refugee crisis on the north Aeagean islands of Lesvos, Chios, Samos, Kos and Leros has exponentially exploded with 42,568 asylum seekers trapped on the islands. The numbers of new arrivals continue to grow at a rate faster than mainland transfers with obvious results – extreme overcrowding, dwindling resources and deplorable conditions. On Lesvos alone, over 21,000 refugees indefinitely endure inhumane conditions, and their numbers are dangerously close to equaling the local population within the capital region of Mytilini.”[9]

Despite the government claiming that it aimed to ‘decongest’ the hotspots, new arrivals outpaced transfers to the mainland. The government then announced its intention to develop closed centres – prisons – rather than the squalid, albeit open, camps that currently exist on the islands. These plans were opposed by locals and foreign volunteers alike, with strident opposition in the form of protests, strikes and blockades of construction sites. However, demonstrations led by refugees faced violence from the police and open hostility from segments of the local population, amongst whom there are numerous fascists. Numerous attacks took place – and continue to take place – against volunteers and their property and premises,[10] including a suspected arson attack against a school for refugees.[11]

The swift uptick in new arrivals following the Turkish government’s announcement provided a fresh target for this hostility, coming at the same time as the ongoing confrontations between the central government, residents of the islands opposed to the plan to build prisons and to the presence of refugees, and refugees, volunteers and those residents that stand in solidarity with them. There were angry reactions from locals, attacks from far-right and racist groups and increased hostility and violence towards NGOs providing assistance on the ground. Small numbers of locals even organised themselves into non-official groups of border guards with the objective of preventing arrivals.[12]

The response from the EU and the member states

The Greek government is also complicit in this violence against volunteers and refugees – either indirectly, through its “campaign to scrutinize NGOs for their humanitarian operations,” stirring suspicion over their motives and activities[13] – or directly, through the deployment of border guards, police officers and troops who are known to beat, intimidate and harass people attempting to cross the border.

Following the Turkish announcement at the end of February, tear gas, water cannons and stun grenades were all deployed to try to repel people,[14] as well as live ammunition, resulting in the death of 22-year-old Muhammed al-Arab (as documented by Forensic Architecture).[15] Those who made – or tried to make – the crossing reported that Greek officials had beaten them up, taken their phones and belongings and left them undressed before sending them back to Turkey[16] - another long-standing practice.[17] The same brutal tactics have allegedly been followed by Greek coast guards, with footage showing them shooting at people in distress at sea whilst they tried to reach the Greek shore.[18] The Greek coast guard also engaged in pushbacks, something with which it has extensive experience.[19] A video of one such pushback was released by the Turkish authorities, who were busy deploying their own special forces to the border with Greece, trapping people in a no-man’s-land between two countries engaging in an absurd game of one-upmanship that put the lives of hundreds of people at risk.

Actions documented by Alarmphone include “grave human rights violations, including shootings and other attacks of boats by masked men who would remove engines and leave people behind in acute distress, as well as many push-and-pull-back operations, some clearly intentioned to sink migrant boats”. Alarmphone has also documented joint activities by “Greek military forces and fascist groups” attacking migrants as they arrive to shores, suggesting collusion between state and non-state actors.[20]

The Greek army announced a 24-hour exercise with live ammunition at the border with Turkey on 2 March: “The broader area of the 24-hour exercise is where also all migrants crossings are in general.”[21] Bulgaria, meanwhile, allegedly opened a dam on the river Evros to make it more difficult for people to cross from Turkey to Greece,[22] whilst also maintaining its long-standing pushback policy to prevent crossings from Turkey to Bulgaria.[23]

Legal measures accompanied these attempts to physically blockade the border. On 2 March, the Greek government responded by issuing a decree suspending the submission of asylum applications due to “extraordinary circumstances and unforeseeable necessity to confront an asymmetrical threat to the national security,” a decision which contravenes EU law and international law.[24] As the UNHCR underlined, the Greek reaction lacked a legal basis.[25] Neither the 1951 Geneva Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees nor EU law allow suspension of the right of seek asylum. Human Rights Watch reported on 20 March that at least 625 people who arrived in the country between 1 and 18 March have been denied the right to seek asylum.[26]

The presidents of the three EU institutions (the European Commission, the European Parliament and the EU Council) paid a visit to Greece on 3 March to reassert their support for the country, despite the introduction of measures against its own acquis and in clear violation of human rights and international law. Ensuing declarations confirmed the securitised approach of the EU towards migration and asylum, with Commission president Ursula Von der Leyen expressing her gratitude to Greece for being “the shield of the EU” and announcing a further €700 million in funding to Greece as well as the deployment of a “rapid border intervention” by Frontex.

According to the Commission’s ‘Action Plan’,[27] which was signed off by the Justice and Home Affairs Council on 13 March,[28] these measures would be accompanied by a new Frontex-coordinated programme for “the quick return of persons without the right to stay,” and the deployment of national asylum experts under the aegis of the European Asylum Support Office. The member states have, at least, provided “70,000 items” of material such as medical equipment, shelters, tents and blankets[29] – although just like the other measures announced, this will do nothing to resolve the profound long-term problems faced by Greece, brought on by the EU’s ‘migration management’ model.

Frontex announced on 13 March that it had deployed 100 additional border guard officers from 22 member states to the Greek land border. These come in addition to the 500 officers already in Greece as part of Frontex’s operations, and the border agency has also received promises of “technical equipment, including vessels, maritime surveillance aircraft and Thermal-Vision Vehicles, for the Frontex maritime Rapid Border Intervention Aegean 2020,” which is due to last two months but can be extended. “The presence of 100 officers from all around Europe underlines the fact that the protection of the area of the European area of freedom, security and justice is a shared responsibility of all Member States and Frontex,” said the Executive Director of Frontex, Fabrice Leggeri.[30] There have so far been no public announcements regarding reinforcements for Frontex operations at Greece’s sea borders.

In contrast to this initial almost-entirely ‘securitarian’ response, Ylva Johansson, the Commissioner for Migration and Home Affairs, travelled to Athens on 12 March and warned that Greek authorities “have to let people apply for asylum.” She also said she wanted to know more about a reported ‘black site’ where people were being detained and beaten,[31] although subsequently said it was up to Greece to investigate the issue.[32] It is unclear what the European Commission – the institution responsible for ensuring that member states correctly implement EU law – has done to ensure that Greece offers people on its territory permission to seek international protection.

The IOM noted that Greece had faced huge pressure on its resources and population on behalf of the EU, and called for the international community to maintain assistance for both Greece and Turkey, where millions of asylum seekers are stranded waiting to cross to the EU and lodge asylum applications.[33] However, humanitarian responses from EU member states have so far been scarce. Five countries (Finland, France, Germany, Luxembourg, and Portugal) have pledged to resettle children stranded in Greece, although little further detail has emerged on these proposals.[34] A collective of seven mayors in Germany stated that on the Greek islands the situation “has dramatically worsened in the last few days”, presenting their cities as among the 140 in Germany declaring themselves as “safe havens” to take in some of the refugees currently on the Aegean islands, focussing particularly on children. While the Bundestag initially voted against an initiative to take in 5,000 children from the islands last week, these seven mayors propose a solidarity plan to admit up to 1,000 children to Germany, either unaccompanied minors under 14 years old, or those in need of urgent medical attention.[35] Whatever is finally agreed, it appears that the border closures and restrictions imposed in the EU in response to the coronavirus outbreak will slow down the relocation of vulnerable children.[36]

No shortage of condemnation

Critical responses to the actions of the Greek state and the EU offer a consistent pattern of outlining basic principles of international law, the universal right to request international protection, the principle of non-refoulement and the illegality of collective expulsion, and calls for adequate hospitality from all EU member states. A common theme has been denouncement of the political game being played between Turkey and the EU with people’s lives. Perhaps the bluntest condemnation came from the journalist Nikolaj Nielsen: “Almost 100 days into its mandate and this European Commission is no longer a credible guardian of the EU treaties.”[37]

In the European Parliament, the Socialists & Democrats group condemned Ursula Von der Leyen’s speech in which she celebrated Greece for being the EU’s “shield”, implying that Europe needs protection from people arriving, when in fact “we are talking about the lives of vulnerable people, of human beings”. Von der Leyen of course began her term as Commission President by introducing the title of ‘Commissioner for protecting our European way of life’ for the official responsible for migration policy. That official, Margaritas Schinas, who is a member of Greece’s New Democracy party, is now officially the ‘Commissioner for promoting our European way of life’. Sensitivity with language does not appear to be a strong point of the current administration in Brussels.

The point taken up by a number of organisations in their responses to the situation, in particular words that allude to invasions or which otherwise militarise the phenomenon of arrivals. ECRE has explained that “inflammatory and military language from EU and national policy-makers contributes to the risk of violence against people seeking protection… ECRE is concerned about the rapidly worsening environment in this regard in both Greece and Turkey.”[38]

Networks of civil society organisations have condemned the political use of migrants as refugees as “pawns”. A number of joint letters have been circulated amongst legal and research organisations, among them an appeal to the European Parliament “to stop violence and the use of force against defenceless people on the border between EU and Turkey and to restore legality and respect for human rights, firstly the right of asylum.” Noting that “governments and European institutions have provided Turkey with an instrument of blackmail that allows people to be used as goods”, the appeal emphasises that “the use of weapons, by army and police, against unarmed civilians is prohibited by international laws and conventions.” The letter calls on the Parliament to ensure that the principle of non-refoulement is respected by admitting asylum applications and committing to a European “redistribution plan” for asylum seekers.[39] Meanwhile, sixty-four organisations released a joint statement to member states urging that they “urgently relocate unaccompanied children from the Greek islands to safety in their territory.”[40]

In more practical terms, the Migreurop network announced plans to “document and take legal action against those responsible for the violations of migrants and refugees’ rights, as well as those of activists acting in solidarity with them.” Their statement underlined that: “No policy aim can justify such gross violations. Exiles fleeing violence must not face the violence of borders while they seek protection. Our organisations are joining their efforts to hold states accountable for their crimes.”[41]

18 March was identified as a significant date as the anniversary of the 2016 signing of the EU-Turkey Statement, with the French legal organisation GISTI proposing the organisation of screenings and demonstrations across Europe documenting the impacts of Europe’s closed borders (the call was subsequently retracted, given the situation brought about by the coronavirus outbreak). Civil liberties organisations in a number of EU states have signed an announcement that resources will be pooled to launch legal proceedings against Greece and the EU.[42]

Larger organisations acting on the international legal stage such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE) have focused on Greece’s obligations under international human rights law, the principle of non-refoulement, and the right to a fair asylum procedure. Amnesty has directly petitioned the Greek government, in light of increased violence against migrants and those helping them, to protect these groups from vigilante and other attacks.[43]

As ECRE commented:

“there is no basis in EU or international refugee law for suspension of acceptance of asylum applications. Article 78(3) Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) provides for the Council to “adopt provisional measures” in case of an emergency due to a “sudden inflow”. If it is invoked, the provisions must comply with EU law, including the Charter of Fundamental Rights; it cannot thus provide a legal base for the suspension of the right to asylum or for expulsions that contravene the principle of non-refoulement. The TFEU also stipulates that the European Parliament must be consulted and the Parliament should be prepared to promote positive alternatives when this happens.”[44]

The UNHCR underlined that invoking Article 78(3) TFEU requires any provisional measures to be adopted by the Council, following a Commission proposal and consultation with the Parliament; it does not activate a state of emergency under which fundamental rights can be cast aside.[45]

There were also numerous critiques of the 2016 EU-Turkey Statement and warnings not to return to the ‘status quo’. ECRE highlighted how the statement gave Turkish President Erdogan the “power” to “extract concessions” from Europe over involvement in Syria. The question of solidarity relates to both Greece and other EU member states, as well as in relation to the EU and Turkey, said ECRE, recalling that Turkey currently hosts 3.6 million refugees from Syria, “more than twice as many as the rest of Europe combined”.[46]

METAdrasi, a Greek organisation that facilitates the reception and integration of refugees and migrants in Greece, underlined “there are empty spaces for unaccompanied children in other EU countries, with families waiting to be reunited with many of these children… Many of these children might one day be European citizens,” drawing attention to the fact that many of those affected by the border closure and suspension of asylum procedures would qualify for international protection.[47]

Those organisations working at sea or on the ground have remarked on the visibility of state and EU sanctioned practices that were once somewhat clandestine, brought to light by the volume of arrivals. In the words of Alarmphone, which is chronicling all push backs and outcomes of requests for assistance (the provision of which is a universal obligation under Article 98 of the Convention of the Law of the Sea), “it is clear that push-backs and violent excesses along the border are daily phenomena, not exceptions.” [48]

Questions have also been raised over the practical impact of an increased presence of Frontex at the land and sea borders between Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey (as well as reinforcements for Greece, the number of border guards deployed by the agency at the Bulgaria-Turkey border has more than doubled from 50 to 110).[49] This increases the potential for the involvement of Frontex in illegal acts by state authorities, for example reviving the question “of whether Frontex will only watch the Bulgarian authorities while they go on with their push-back practice.”[50]

Critical responses to the approach taken by Greece and backed up by the EU have not solely come from civil society organisations. Frontex also-coordinates Operation Poseidon, which involves border and coast guards and vessels of EU member and Schengen associated states in patrolling the sea between Turkey and Greece’s Aegean islands. A Danish patrol boat that was part of this operation last week refused orders to push back migrants at sea.[51] However, the question remains: who ordered the push back?

Conclusion

On 13 March, the New York Times reported that Turkey was “winding down its two-week operation to aid the movement of tens of thousands of people toward Europe, following a tough on-the-ground response from Greek border guards and a tepid diplomatic reaction from European politicians.”[52] This return to playing the role of Europe’s border guard may have put an end to the dramatic footage of people on the move, but the situation for those trapped on the Greek islands – or elsewhere in or en route to the EU – remains unchanged, as do the long-term, structural problems created by the EU’s asylum and migration policies.

Greek and other officials were keen to point out that neither Greece nor the EU could be blackmailed by Erdoğan. This was clearly profound nonsense, given the situation unfolding in front of their eyes. Allowing people to try to cross the border was an obvious attempt to extract concessions from the Europeans, whether in financial terms or for support for Turkey’s military actions in Syria.

Despite this clear demonstration of how easily the EU’s ‘at all costs’ approach to keeping refugees off its territory can be undermined, the EU is still aiming to renegotiate the controversial 2016 Agreement with Turkey.[53] Given this willingness to cooperate with dubiously democratic governments with a minimal (at best) commitment to human rights, the EU’s commitments to its own supposed founding principles can no longer be taken seriously – although to many observers, this has something that has long been obvious.

Despite criticisms from European officials that the Turkish government was using people as pawns, this was precisely the basis of the EU-Turkey Deal. It should not be forgotten that it includes provisions allowing the resettlement into the EU of one Syrian for every Syrian who is deported from Greece to Turkey.[54] In this morally-repugnant trade in flesh, one ‘unworthy’ person has to risk their life to reach Greece so that a ‘worthy’ individual in Turkey can receive protection in Europe. The fact that those provisions of the agreement have been little-used does not undermine their significance.

Ultimately, the episode reveals the profound, long-term failures of the EU’s approach to asylum and migration. Rather than working together to support those needing international protection (or even to assist those seeking to ‘improve their lives’, i.e. ‘economic migrants’, by opening up legal pathways for labour migration) EU and national institutions have barricaded people onto islands, into camps and done deals with dictators and failed to uphold basic international legal principles – an approach that now, in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, is creating even greater risks to peoples’ lives.

In the face of a profound humanitarian crisis in Greece and at its borders with Turkey, the main response has been to take further repressive measures – essentially, an attempt by the EU and the member states to dig themselves out of the hole they have created. Until this approach fundamentally changes, the only thing we can be certain of is that the daily miseries inflicted upon ordinary people by this regime will continue, and that they will continue to remain paws at the hands of the powerful and their interests.

Chris Jones, Jane Kilpatrick, Yurema Pallarés Pla

Endnotes

[1] Degar Akal, ‘EU-Turkey refugee deal: Will the fragile agreement hold?’, DW, 3 February 2020, https://www.dw.com/en/eu-turkey-refugee-deal-will-the-fragile-agreement-hold/a-52237907

[2] UNHCR, ‘Greece’, accessed 23 March 2020, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean/location/5179

[3] Bethan McKernan and Daniel Boffey, ‘Greece and Bulgaria crack down on Turkish borders as refugees arrive’, The Guardian, 28 February 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/28/tensions-rise-between-turkey-and-russia-after-killing-of-troops-in-syria

[4] European Commission, ‘Third Annual Report on the Facility for Refugees in Turkey’, COM(2019) 174 final/2, 15 April 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/com_2019_174_f1_communication_from_commission_to_inst_en_v5_p1_1016762.pdf

[5] ‘Young Turks in despair, blame Syrians, research says’, Ahval, 11 February 2020, https://ahvalnews.com/turkey-youth/young-turks-despair-blame-syrians-research-says; ‘Rising xenophobia: Attack highlights Turkish anger at foreigners’, Arab News, 5 February 2020, https://www.arabnews.com/node/1623171/middle-east; David Gauthier-Villars and Nazih Osseiran, ‘Turkey Aims to End a Backlash by Sending Syrian Refugees Home’, The Wall Street Journal, 9 August 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/turkey-aims-to-end-a-backlash-by-sending-syrian-refugees-home-11565343121

[6] ‘Turkey says Idlib ceasefire details largely agreed on with Russia’, Al Jazeera, 12 March 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/03/turkey-idlib-ceasefire-details-largely-agreed-russia-200312110120296.html

[7] Ragip Soylu, ‘Turkey to open Idlib border and allow Syrian refugees free passage to Europe’, Middle East Eye, 27 February 2020, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/turkey-syrian-refugees-free-passage-europe-soldiers-killed-Idlib

[8] Suzan Fraser, ‘Turkey: Elite police going to stop Greece's migrant pushback’, ABC News, 5 March 2020, https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/turkey-vows-justice-migrant-killed-border-greece-69405603

[9] Douglas F. Herman, ‘AYS Special: Lesvos well beyond the brink (this is what we know so far)’, Are You Syrious?, 1 March 2020, https://medium.com/are-you-syrious/ays-special-lesvos-well-beyond-the-brink-this-is-what-we-know-so-far-7c11873e12f8

[10] Tamara Qiblawi, Chris Liakos, Barbara Arvanitidis and Phil Black, ‘Desperate migrants keep coming. Now vigilantes are threatening the welcomers’, CNN, 10 March 2020, https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/10/europe/greece-lesbos-migrants-vigilantes-intl/index.html; Justing Higginbottom, ‘‘It’s a powder keg ready to explode’: In Greek village, tensions simmer between refugees and locals’, CNBC, 2 March 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/01/refugee-crisis-in-greece-tensions-soar-between-migrants-and-locals.html

[11] Judy Maltz, ‘Arson Suspected in Fire That Destroyed School for Refugees in Lesbos Set Up by Jews and Arabs’, Hareetz, 8 March 2020, https://www.haaretz.com/world-news/europe/.premium-arson-suspected-in-fire-that-destroyed-israeli-run-school-for-refugees-in-lesbos-1.8639561

[12] ‘Citizen patrols ward off 'invasion' on Greek-Turkish border’, France 24, 5 March 2020, https://www.france24.com/en/20200305-citizen-patrols-ward-off-invasion-on-greek-turkish-border

[13] Douglas F. Herman, ‘AYS Special: Lesvos well beyond the brink (this is what we know so far)’, Are You Syrious?, 1 March 2020, https://medium.com/are-you-syrious/ays-special-lesvos-well-beyond-the-brink-this-is-what-we-know-so-far-7c11873e12f8

[14] Suzan Fraser, ‘Turkey: Elite police going to stop Greece's migrant pushback’, ABC News, 5 March 2020, https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/turkey-vows-justice-migrant-killed-border-greece-69405603

[15] ‘Joint statement on the ongoing violence at the Greece-Turkey border’, Forensic Architecture, 5 March 2020, https://forensic-architecture.org/programme/news/joint-statement-on-the-ongoing-violence-at-the-greece-turkey-border

[16] ‘Jomana Karasheh and Gul Tuysuz, ‘Migrants say Greek forces stripped them and sent them back to Turkey in their underwear’, CNN, 7 March 2020, https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/07/europe/turkey-greece-migrants-clash-intl/index.html

[17] ‘Greece Videos Show Apparent Illegal Pushback of Migrants’, Der Spiegel, 13 December 2019, https://www.spiegel.de/international/globalsocieties/greece-videos-show-apparent-illegal-pushback-of-migrants-a-1301228.html

[18] ‘Greek coast guards fire into sea near migrant boat’, BBC News, 2 March 2020, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/world-europe-51715422/greek-coast-guards-fire-into-sea-near-migrant-boat

[19] Kaamil Ahmed, ‘Refugee boats leaving Turkey for Greece attacked at sea’, Middle East Eye, 2 March 2020, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/refugee-boats-attacked-near-greece-coast-turkey-sea

[20] ‘Escalating Violence in the Aegean Sea - Attacks and human rights abuses by European Coastguards, 1-3 March 2020’, Alarmphone, 4 March 2020, https://alarmphone.org/en/2020/03/04/escalating-violence-in-the-aegean-sea/

[21] ‘Evros: Greek Army announces exercise with live ammunition on March 2’, Keep Talking Greece, 2 March 2020, https://www.keeptalkinggreece.com/2020/03/02/greece-army-exercise-live-ammunition-mar2/

[22] Tasos Kokkindis, ‘Bulgaria Floods Evros River to Prevent Migrants Storming Greek Borders’, Greek Reporter, 10 March 2020, https://greece.greekreporter.com/2020/03/10/bulgaria-floods-evros-river-to-prevent-migrants-storming-greek-borders

[23] ‘Bulgaria is not changing its push-back policy at its border to Turkey’, Bordermonitoring Bulgaria, 2 March 2020, https://bulgaria.bordermonitoring.eu/2020/03/02/bulgaria-is-not-changing-its-push-back-policy-at-its-border-to-turkey/

[24] Tweet by Kyriakos Mitsotakis, 1 March 2020, https://twitter.com/PrimeministerGR/status/1234192926328139776?s=20. Translation of the decree into English, https://docs.google.com/document/d/1yA782Vi56KnIhs2yVehXgkMYQeCieaPq5coWNHqh6xs/edit

[25] ‘UNHCR statement on the situation at the Turkey-EU border’, UNHCR, 2 March 2020, https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/news/press/2020/3/5e5d08ad4/unhcr-statement-situation-turkey-eu-border.html

[26] ‘Greece: Grant Asylum Access to New Arrivals’, Human Rights Watch, 20 March 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/20/greece-grant-asylum-access-new-arrivals

[27] European Commission press release, ‘Migration: Commission takes action to find solutions for unaccompanied migrant children on Greek islands’, 6 March 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_406

[28] Council of the EU, ‘Outcome of the Council meeting, 3756th Council meeting, Justice and home affairs’, 6582/20, 13 March 2020, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/42944/st06582-en20.pdf

[29] European Commission, ‘EU mobilises support to Greece via Civil Protection Mechanism’, 6 March 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/echo/news/eu-mobilises-support-greece-civil-protection-mechanism_en

[30] Frontex, ‘Frontex launches rapid border intervention on Greek land border’, 13 March 2020, https://frontex.europa.eu/media-centre/news-release/frontex-launches-rapid-border-intervention-on-greek-land-border-J7k21h

[31] Jennifer Rankin, ‘Greece warned by EU it must uphold the right to asylum’, The Guardian, 12 March 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/12/greece-warned-by-eu-it-must-uphold-the-right-to-asylum

[32] Nikolaj Nielsen, ‘Up to Greece to investigate 'black site', EU says’, EUobserver, 12 March 2020, https://euobserver.com/migration/147704

[33] IOM, ‘IOM Urges Restraint, Calls for a Humane Response on EU-Turkey Border’, 5 March 2020, https://www.iom.int/news/iom-urges-restraint-calls-humane-response-eu-turkey-border

[34] ‘EU to take in some child migrants stuck in Greece’, BBC News, 9 March 2020, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-51799470

[35] Davis VanOpdorp, ‘Seven German mayors: Allow us to accept underage refugees’, DW, 6 March 2020, https://www.dw.com/en/seven-german-mayors-allow-us-to-accept-underage-refugees/a-52657792

[36] Emma Farge, ‘EU border restrictions will hit transfers of child refugees - UN official’, Thomas Reuters Foundation, 17 March 2020, https://news.trust.org/item/20200317171441-3e5w8/

[37] Nikolaj Nielsen, ‘Migrants: EU commission not fit to guard treaties’, EUobserver, 6 March 2020, https://euobserver.com/migration/147657

[38] ‘ECRE Statement on the Situation at the Greek Turkish Border’, 3 March 2020, https://www.ecre.org/ecre-statement-on-the-situation-at-the-greek-turkish-border/

[39] ‘The European Parliament must intervene to stop violence, the use of force and human rights violations at the EU-Turkey border’, change.org, https://www.change.org/p/parlamento-europeo-migranti-il-parlamento-europeo-fermi-le-violenze-e-la-violazioni-dei-diritti-umani

[40] ‘NGOs' Urgent Call to Action: EU Member States Should Commit to the Emergency Relocation of Unaccompanied Children from the Greek Islands’, Human Rights Watch, 4 March 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/04/ngos-urgent-call-action-eu-member-states-should-commit-emergency-relocation

[41] ‘A coalition to “shield” migrants and refugees against violence at the borders’, Migreurop, 5 March 2020, http://www.migreurop.org/article2961.html?lang=en

[42] Ibid.

[43] ‘Greece: Inhumane asylum measures will put lives at risk’, Amnesty International, 2 March 2020, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/03/greece-inhumane-asylum-measures-will-put-lives-at-risk/

[44] ‘ECRE Statement on the Situation at the Greek Turkish Border’, 3 March 2020, https://www.ecre.org/ecre-statement-on-the-situation-at-the-greek-turkish-border/

[45] ‘UNHCR statement on the situation at the Turkey-EU border’, UNHCR, 2 March 2020, https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/news/press/2020/3/5e5d08ad4/unhcr-statement-situation-turkey-eu-border.html

[46] ‘ECRE Statement on the Situation at the Greek Turkish Border’, 3 March 2020, https://www.ecre.org/ecre-statement-on-the-situation-at-the-greek-turkish-border/

[47] ‘Greece/EU: Urgently Relocate Lone Children’, Human Rights Watch, 4 March 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/04/greece/eu-urgently-relocate-lone-children

[48] ‘At the Greek-Turkish border, politicians play with people’s lives’, Alarmphone, 1 March 2020, https://alarmphone.org/en/2020/03/01/at-the-greek-turkish-border-politicians-play-with-peoples-lives/

[49] ‘Bulgaria is not changing its push-back policy at its border to Turkey’, Bordermonitoring Bulgaria, 2 March 2020, https://bulgaria.bordermonitoring.eu/2020/03/02/bulgaria-is-not-changing-its-push-back-policy-at-its-border-to-turkey/

[50] ‘The (unseen) violent and forced push-backs on the Bulgarian-Turkish land border’, Bordermonitoring Bulgaria, 10 March 2018, https://bulgaria.bordermonitoring.eu/2018/03/10/the-unseen-violent-push-backs-on-the-bulgarian-turkish-land-border/

[51] Laurie Tritschler, ‘Danish boat in Aegean refused order to push back rescued migrants’, Politico Europe, 6 March 2020, https://www.politico.eu/article/danish-frontex-boat-refused-order-to-push-back-rescued-migrants-report/

[52] Matina Stevis-Gridneff and Patrick Kingsley, ‘Turkey Steps Back From Confrontation at Greek Border’, The New York Times, 13 March 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/13/world/europe/turkey-greece-border-migrants.html

[53] Davis VanOpdorp, ‘EU remains committed to refugee pact with Turkey’, DW, 9 March 2020, https://www.dw.com/en/eu-remains-committed-to-refugee-pact-with-turkey/a-52698050

[54] “For every Syrian being returned to Turkey from Greek islands, another Syrian will be resettled from Turkey to the EU taking into account the UN Vulnerability Criteria.” See: ‘EU-Turkey statement, 18 March 2016’, Council of the EU, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/03/18/eu-turkey-statement/

Our work is only possible with your support.

Become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Spotted an error? If you've spotted a problem with this page, just click once to let us know.